In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

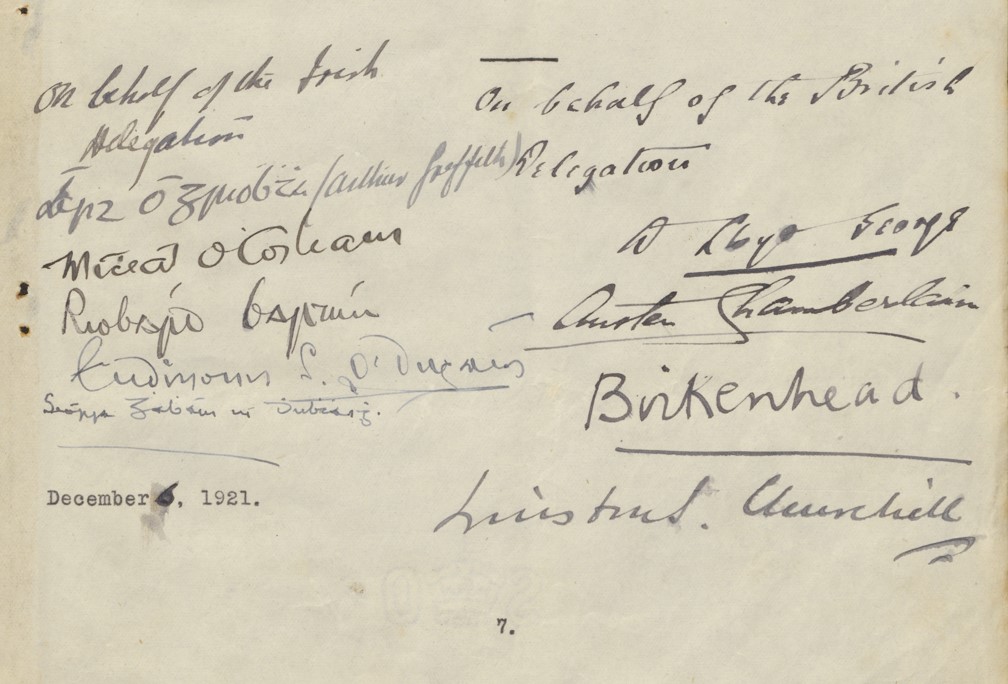

The Politics of the Treaty

Though the Treaty of 1921 gave Ireland an independence that had eluded previous generations, the oath of fidelity to the British king was seen by many as a betrayal, write UCC's Mícheál Ó Fathartaigh and Liam Weeks

The difficult circumstances under which the Anglo-Irish Treaty was negotiated in 1921 impacted severely on its legacy. The domestic and international press, not to mention foreign governments, welcomed the agreement, partly because it was sold as an end to the Irish conflict. The public reception, however, was much more muted, with the mood the night the Treaty was signed in stark contrast to the celebrations that had followed the declaration of the truce that ended the War of Independence five months earlier. Celia Shaw, a student at University College Dublin in 1921, noted in her diary on 6 December, ‘no-one knows what to think. There is an oath, though subtly worded ... not a bonfire, not a flag, not a hurrah.’ Even though the Treaty achieved for Ireland what had eluded centuries of previous nationalist movements, the Sinn Féin party that delivered it split irrevocably over the Treaty. Why was this? What was so contentious about the Treaty?

For a document of such profound significance, one that created a state and dissolved a union, resurrected one nation and reconstituted another, the Treaty was decidedly vague. This was in the best British tradition of things, given that even today Britain foregoes having a written constitution in the conventional understanding. Article 1 exemplified the almost perfunctory nature of the Treaty. It managed to bring the Irish Free State, independent Ireland, into the world with barely an introduction. Instead, with a very simple legal formulation it defined the new Irish Free State by referring only to precedent. That precedent was the status of four dominions, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, and insofar as they were politically independent and nationally sovereign, so would be the Irish Free State. Westminster retained some scope for legislative interference, but it was quite negligible (and by 1921 it was, moreover, dormant). Therefore, politically speaking, dominion status meant that the Irish Free State would be substantively independent.

Indeed, the idea of a so-called ‘Canada model’, touted by recent British governments as a post-Brexit political solution after it left a large union of its own, was what was prescribed for Ireland in Article 2 of the Treaty. The model proposed in 1921 involved the Irish Free State attaining the same freedoms as Canada, which had participated in the post-war Paris Peace Conference as a quasi-autonomous nation alongside not just Britain, but the British Empire, of which it was supposed to be just a part. While Britain had the right to veto legislation that the Canadian parliament passed, it had not done so since 1886, and a new convention of parliamentary parity between London and Ottawa had emerged. To all intents and purposes, Canada, through the independence of its parliament, had substantive political independence and internal sovereignty, and so would the Irish Free State.

At the same time, the Treaty stopped short of a republic. The name for what had been called ‘Southern Ireland’ under the 1920 Government of Ireland Act was to be the Irish Free State. Saorstát was one of two words favoured by Irish-speakers for ‘republic’, even if it translated literally as ‘free state’ (the other being poblacht). It has been claimed that the British may not have fully understood the meaning of the word, and that the Irish delegation had gotten one over on their counterparts, but there was never any doubt amongst the British that free state did not connote republic. The unequivocal older language of ‘British Empire’ was also used to describe what the Irish Free State would continue to be a part of, and not the wishy-washy newer language of ‘British Commonwealth’ (which was used elsewhere in the Treaty). From an Irish perspective, these optics were very important, and were what made the Treaty so divisive.

Members of the Irish negotiation committee returning to Ireland in December 1921 (National Library of Ireland, W. D. Hogan Collection

The other feature that proved so controversial was the oath. More than anything else in the Treaty, it was this that caused the split in Sinn Féin and the resultant civil war. The popular impression is that the oath of allegiance was to the British king, but it was in fact to be sworn to the forthcoming Constitution of the Irish Free State. It was fidelity that was to be given to the king, which was less than that demanded in the other dominions where members of parliament were obligated to swear allegiance to the British monarch. Nevertheless, for anti-Treaty republicans the oath was a betrayal of the Irish republic as proclaimed at Easter 1916 and as established by the Irish people through the election victories of Sinn Féin from 1918.

The second part of the oath has largely escaped scrutiny but it was an even greater thorn in the side of republican aspirations, as it referred to the ‘the common citizenship of Ireland with Great Britain and her adherence to and membership of the group of nations forming the British Commonwealth of Nations.’ This obliged TDs to acknowledge not even that they were now actually citizens of an Irish dominion of the Crown but, instead, that they were, and that they had continued to be, citizens of the union itself. Put bluntly, it obligated them to acknowledge that the people of Ireland remained British.

A feature of the Treaty that attracted little attention at the time but which potentially could have had a huge impact was Article 5, under which the Irish Free State was to assume liability for a portion of British public debt and its war pensions. In 1925 the British government calculated this to be £156 million, a not insubstantial 80 per cent of Irish GNP at the time. In what economist John FitzGerald has described as Ireland’s greatest ever financial success, this was negotiated down to £5 million in an agreement between the British and Irish governments that sealed the fate of another potentially significant article of the Treaty, Article 12.

This article had two clauses, the first of which stated that all that the parliament of Northern Ireland had to do in order to confirm the future of Northern Ireland, and to opt out of the Irish Free State, was to present an official petition to King George V within one month of the formal creation of the Irish Free State. This it duly did, as soon as it could, in December 1922.

The reason the Irish delegation that negotiated the Treaty agreed to this wording was because of the second clause of Article 12, which concerned the establishment of a commission to decide on the boundary of Northern Ireland, ‘in accordance with the wishes of the inhabitants, so far as may be compatible with economic and geographic conditions’. Arthur Griffith and Michael Collins had been led to believe by the British prime minister David Lloyd George that this would recommend the transfer of Tyrone and Fermanagh, and parts of Armagh, Derry and Down to the Irish Free State. What would remain of Northern Ireland following such a stripping would be economically unviable.

In what was a glaring and naïve error by the Irish delegation, none of these assumptions were written down, and by the time the Boundary Commission met in 1925, Ireland was dealing with the aftermath of a civil war, Griffith and Collins were dead, and Lloyd George was gone from office. The final report of the commission was never published, as its leak in the Conservative Morning Post newspaper in December 1925 suggested nothing like the transfer of territory to the Irish Free State that Griffith and Collins had envisaged; moreover, it proposed ceding, for instance, sections of east Donegal to Northern Ireland. The consequence was that the Irish government rushed to London to prevent the publication of the report, which it achieved, albeit with an acceptance that the border was not to be altered. Instead of the anticipated territorial gains, what accrued to the Irish Free State was the aforementioned reduction of its contribution to the British national debt.

By that stage, the stepping-stone that Michael Collins had predicted the Treaty to be was achieving the advanced freedom that he had predicted, if not for the whole island. The Treaty had been sold by Lloyd George to the British parliament and public as a solution to the perennial Irish question, but the Ulster problem had not gone away. The failure of the Boundary Commission and, indeed, the failure of the Treaty, to produce a workable compromise amenable to both communities on the island ensured that it was only a matter of time before the dreary steeples of Fermanagh and Tyrone emerged once again.

In more recent times, the conflict over the Northern Ireland backstop and later the Northern Ireland protocol have highlighted the biggest failure of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. It seems that the three primary groupings – nationalist Ireland, unionist Ulster and the British government – may all want now, as they did then, something entirely different. The contemporary political players are cognisant, if they had not been before, of why it was so difficult to manufacture in the Treaty a long-lasting solution that would appease all on these islands. Could it be, as the American political scientist Richard Rose depressingly asked in the 1980s, ‘the problem is, there is no solution’?

Dr Liam Weeks (University College Cork) and Dr Mícheál Ó Fathartaigh (Dublin Business School) are co-authors of the recently published Birth of a State. The Anglo-Irish Treaty (Irish Academic Press, 2021).

– This article by was first published in the special Irish Examiner Supplement 'The Road to Civil War', published 31 January 2022 –

The UCC School of History’s two-day virtual conference, which took place on 1-2 October 2021, explored the complex issues and the processes surrounding the Anglo-Irish negotiations. Find the full conference proceedings here