In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Dr Donal Ó Drisceoil explains how rail workers refused to carry British military personnel or munitions in an effective manifestation of passive resistance between May and December 1920

The organised labour movement made a number of significant interventions in the independence struggle. In 1918, for example, the general strike against conscription was a huge success, as was the April 1920 two-day strike that forced the British government to release republican hunger-strikers. However, the longest-running and arguably most effective action was the so-called ‘munitions strike’ of May to December 1920, when railway workers placed an embargo on the transportation of British military forces and munitions. Historians have described this as ‘the largest manifestation of passive resistance during the war of independence’ and shown how it ‘very considerably disrupted British attempts to put down the Irish revolt’. The British army commander in Ireland, General Neville Macready, called it ‘a serious set-back to military actions’ while the Chief Secretary Sir Hamar Greenwood admitted that it put the Irish administration in a ‘humiliating and discreditable’ position.

In May 1920 London dockers refused to load a ship with munitions for the Polish government’s war on Soviet Russia. Dublin dockers from the ITGWU followed their lead, but in their case, they refused to handle British munitions. Irish members of the British-based National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) then adapted its union’s support of the British dockers to the Irish situation and followed the lead of the Dublin dockers. The NUR had directed members to refuse to handle ‘any material which is intended to assist Poland against the Russian people.’ Its Irish members then claimed the right to refuse to carry munitions and armed troops in Ireland on the same principle – lives were being lost here at the hands of militarism, just as they were in Russia.

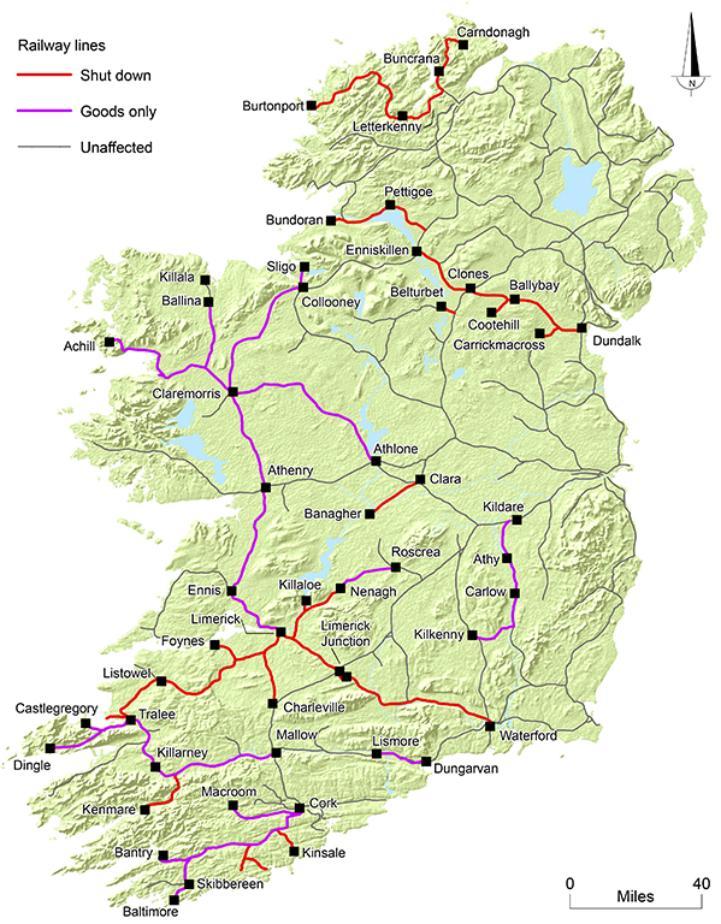

Map showing the Irish railway lines affected by the ‘munitions strike’ of May to December 1920. [Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution, (CUP, 2017)]

The railway embargo coincided with the escalation of the military conflict in Ireland from the Summer of 1920, as the IRA went on the offensive and the Crown forces responded in kind. This was also when the Dáil’s ‘counter-state’ began to emerge, primarily in the shape of republican courts, and Sinn Féin won control of local government – all of which presented a profound challenge to the legitimacy and effectiveness of British governance in Ireland.

The British union refused to back its Irish members in their challenge to the government, but the Irish trade union movement rowed in behind them with financial and other aid.

The railway companies dismissed up to a thousand workers and railway lines closed or or partially closed across the country outside of the north-east (see map). As well as seriously hampering the British war effort, the action was having a severe economic impact and was adding to the suffering of the civilian population. With the government threatening to completely shut down of the railway system and dismiss several thousand workers, the trade unions decided to end the action in December 1920.

While this was technically a ‘victory’ for the British government, the seven-month action by the railway workers had seriously impacted on British military effectiveness and struck a major symbolic blow for Irish independence.

– This article by Donal Ó Drisceoil was first published in the special Irish Examiner Supplement commemorating the centenary of the death of Lord Mayor Tomas MacCurtain on 20 March 2020 –