In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

King Street (MacCurtain Street) RIC barracks after it was attacked and destroyed by Cork No.1 Brigade IRA on July 20th. 1920.

The failure of the Munster Volunteers to join the Rising had unintended benefits as Munster largely escaped the British crackdown, writes John Borgonovo

The 1916 Easter Rising transformed Irish politics and set the stage for the ensuing War of Independence. An armed insurrection by the Irish Volunteers organisation (in conjunction with the Irish Citizen Army and Cumann na mBan), was crushed after a week. Fighting was confined to Dublin, Wexford, Galway, and Meath, and followed by mass arrests which unravelled much of the Volunteer organisation in those areas. However, owing to contradictory orders from Irish Volunteers headquarters, well-organized Volunteer units in the province of Munster sat out the hostilities.

The failure of the Munster Volunteers to join the rebellion had unintended benefits. Munster largely escaped the ensuing government crackdown, as local organisations were driven underground but not destroyed. These same Volunteer units, in Cork, Limerick, Tipperary, Clare, and Kerry, led the reorganisation of the Irish Volunteers in the summer of 1916. Going forward, the Munster IRA shed leaders who had proved reluctant during the Rising and replaced them with committed militants. The Munster Volunteers retained solid unit structures and cadres with years of organizing experience, which enabled them to rapidly form new units and recruit members when the Irish Volunteers expanded into a mass movement in 1917. Parish-by-parish organisations built up three wings of the independence movement: the new Sinn Féin political party, the republican women’s organisation, Cumann na mBan, and the paramilitary Irish Volunteers (soon to become known as the Irish Republican Army, or IRA). By 1918 these organisations dominated three of Ireland’s four provinces.

The independence movement defied wartime suppression by the British government, laid out a convincing case for Irish self-determination, and led mass civil resistance which defeated military conscription in Ireland during 1918. The anti-conscription campaign further strengthened the IRA, as thousands of recruits flooded into the organisation. At the end of 1918, Sinn Féin swept the General Election, winning (with three exceptions) every parliamentary seat outside of Ulster. Rather than take their seats in the House of Commons, the elected Sinn Féin representatives gathered at the Mansion House in Dublin, established Dáil Éireann, and declared national independence.

Republicans attempted to secure Irish independence at the Paris Peace Conference, which was then redrawing the map of Europe. Ireland had a solid case for self-determination, and Sinn Féin’s dramatic 1918 electoral victory gave it a democratic mandate. US President Woodrow Wilson claimed to have fought the First World War to bring self-determination to small nations, and he held strong leverage over Great Britain owing to billions in outstanding war loans. Sinn Féin expected support from the United States given the strength of the Irish-American lobby. The Paris Peace Conference ultimately recognised independence in places like Finland, Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia. However, it also became clear that victorious powers like Great Britain had no intention of giving up any of their own claimed territory. Ultimately, the Sinn Féin delegation was denied entry to the Peace Conference, as were representatives of colonized peoples from places like India, Egypt, and Vietnam. By 1919, the non-violent Irish strategy had failed, leaving an opening to IRA militants in Munster and elsewhere who advocated armed resistance to the government.

Popular histories often refer to the Soloheadbeg Ambush of January 1919 as the first shots of the War of Independence. Yet, the IRA’s armed insurgency built slowly, in a highly localized manner throughout 1919. Since the end of the Conscription Crisis, IRA General Headquarters (known as GHQ) had no clear policy about armed resistance to the government. IRA officers in active Munster units lobbied GHQ to take a more aggressive policy towards the Crown forces.

Often acting without authority, IRA units in Cork, Kerry, Limerick, and Tipperary engaged in a series of armed actions against the Crown forces, primarily weapons seizures and jail breaks. Even before Soloheadbeg, in April 1918, Kerry Volunteers got into a deadly shootout after briefly seizing the RIC barracks at Gortatlea. In July, at the Mouth of the Glen (near Balingeary), IRA Volunteers disarmed two Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) constables, wounding one. In early November 1918, while resisting a raid on his lodging house, Cork No. 1 Brigade IRA officer Denis MacNeilus shot and wounded a RIC constable. The following week, his Cork city colleagues broke MacNeilus out of Cork Men’s Gaol, in what was arguably the IRA’s most dramatic success since the Easter Rising. Operating independently of each other throughout 1919, other IRA brigades in County Cork disarmed parties of British soldiers at Rathclaren and Fermoy, and rushed RIC barracks at Eyeries and Araglen. Limerick and Tipperary Volunteers had staged bloody rescues of IRA prisoners at Knocklong train station and the Limerick Workhouse Infirmary (the latter failed).

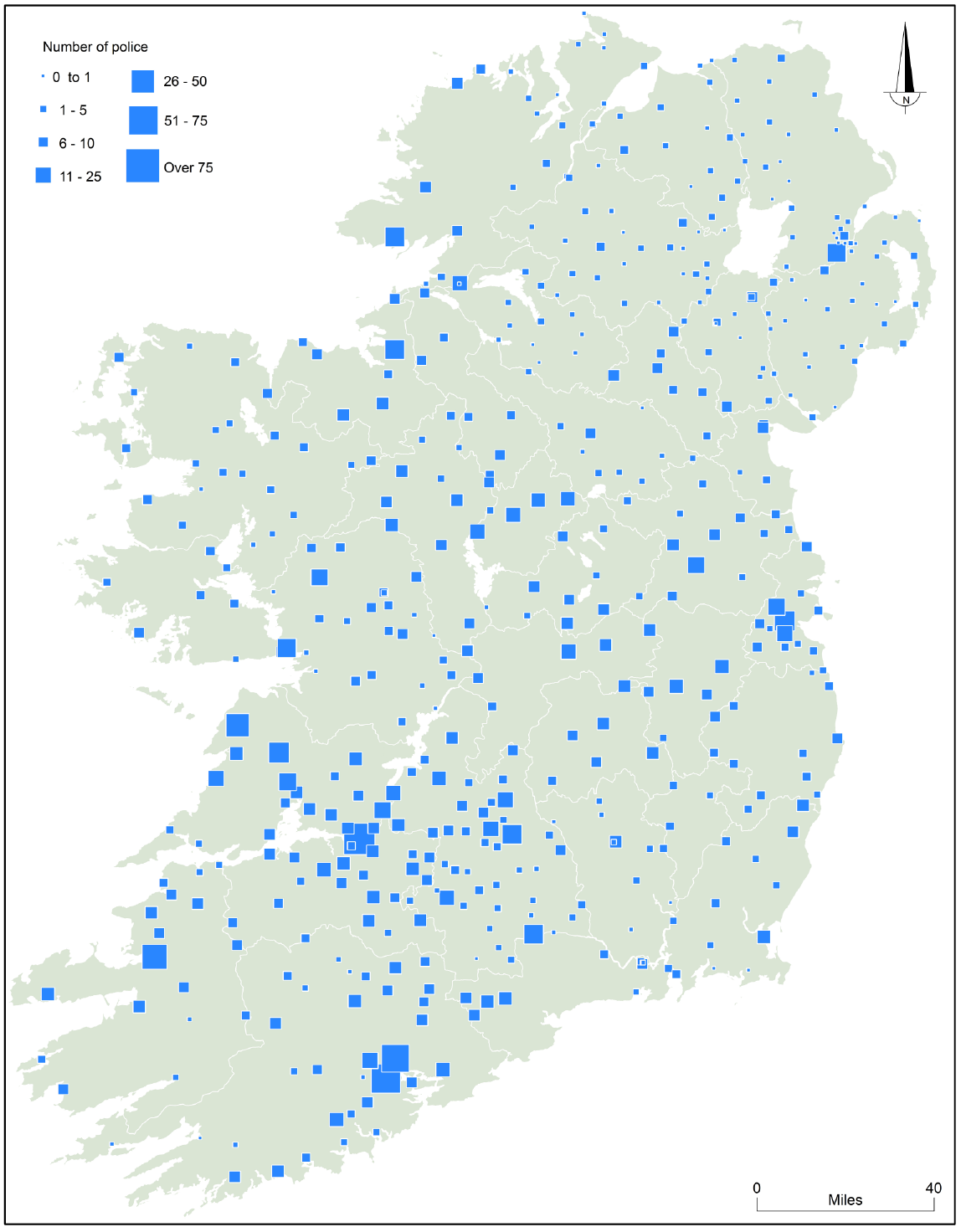

Map showing the strength of the RIC at various locations in Ireland 1919-20. [Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution, (CUP, 2017)]

Rather than crack down on the Munster IRA, the IRA GHQ leadership duo of Richard Mulcahy and Michael Collins sought to bring militants under their personal control in Dublin. In mid-July 1919, Collins formed his famed ‘Squad’ in July 1919 and promptly recruited South Tipperary’s four most active IRA officers into it, despite their lack of familiarity with Dublin. Later in 1919, Collins focused on assassinating the Lord Lieutenant, Field Marshal John French, in Phoenix Park. He tried to convince Cork IRA officers to join the French ambush (Tomás MacCurtain joined one aborted attempt), which seemed, in part, to have been a response to their growing demands for action. IRA leader and historian Florrie O’Donoghue later explained the thinking in Cork: ‘In the absence of a policy of action there was grave danger that the Volunteer organisation would disintegrate. A fair state of training, organisation, and discipline had been attained; training was beginning to pall; police aggression, raids, and arrests were likely to increase where no effective resistance was offered;…the political field did not appear to offer any reasonable hope that freedom would be achieved without fighting for it.’

Tomás MacCurtain appears to have feared an internal split if GHQ continued to delay the proposed IRA offensive. Under pressure, GHQ finally approved attacks on multiple police stations within the Cork No. 1 Brigade area (Mid-Cork and Cork city) on the night of 3-4 January 1920. Four barracks were chosen in different IRA battalion areas: Carrigtwohill (for East Cork units), Ballygarvan (south side Cork city units), Kilmurray (Macroom area units), and Inchigeela (Ballyvourney area units).

Militarily, the barrack assaults achieved only mixed results. The Ballygarvan effort was never undertaken, owing to a reluctant commander who was soon replaced. At Kilmurray and Inchigeela, parties of Irish Volunteers surrounded and fired into the stations, but police defenders held them at bay for two hours until they departed. Greater success was achieved by the East Cork Volunteers in the village of Carrigtwohill. Led by Mick Leahy, their two-hour assault on the RIC barracks involved scores of Volunteers from the Cobh and Midleton areas. They sealed off the station, gained entry by blowing a breach in the gable wall, and forced the surrender of the constables after a brief fight inside. The capture of the Carrigtwohill RIC barracks was arguably the IRA’s most spectacular victory since 1916, and signified the start of a broad IRA offensive against the RIC, which was most pronounced in Munster.

The first half of 1920 became associated with highly organized IRA sieges of rural RIC barracks though there were also numerous attacks on isolated police constables and patrols. From April to July 1920, the Cork No. 1 Brigade targeted isolated police posts at Blarney, Farran, Inchigeela, Clondrohid, and Cork city (MacCurtain Street). In the same period, similar IRA assaults occurred in South Tipperary at Rearcross and Hollyford, in Limerick at Kilmallock and Ballylanders, and in Kerry at Goratlea and Scartaglin. When counting Volunteers who blocked roads and scouted for Crown force reinforcements, each episode often involved hundreds of participants. These early efforts were intended to involve as many Volunteers as possible, to give them a sense of purpose, involvement, and experience of armed actions. Even when unsuccessful, the attacks raised participant’s confidence and efficiency. These same units led the IRA’s development of guerrilla warfare when the conflict escalated in the second half of 1920.

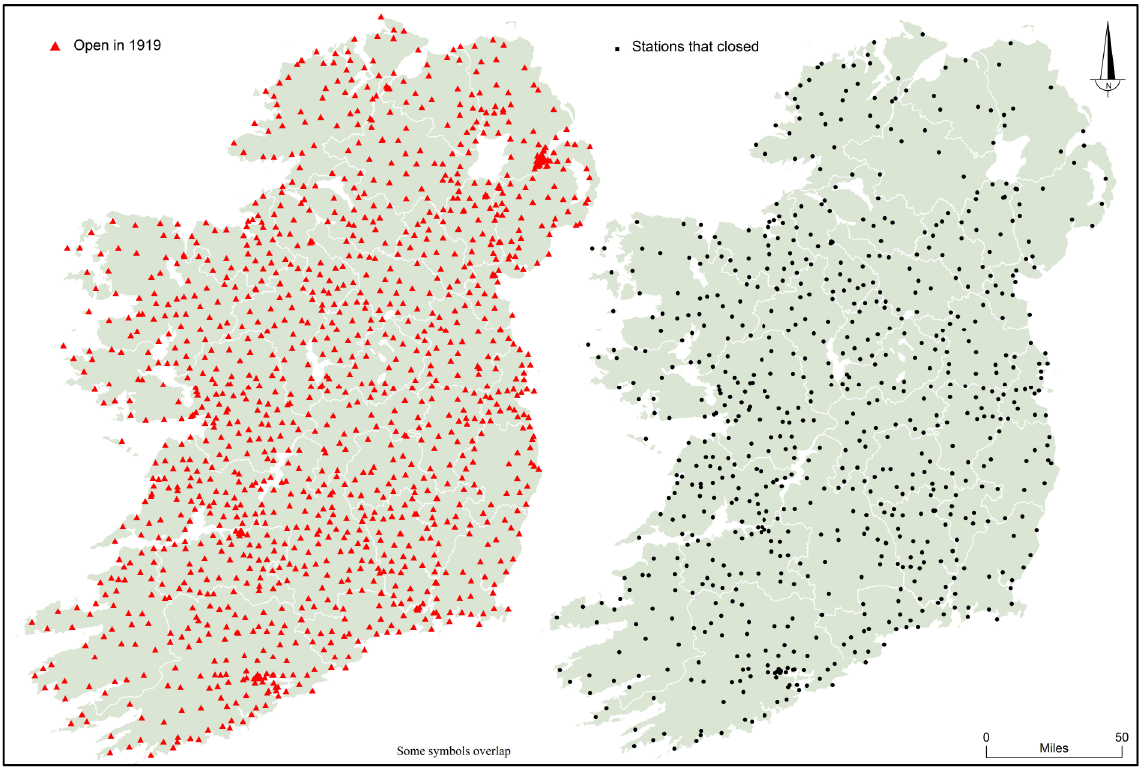

The consolidation of the RIC force 1919-20. [Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution, (CUP, 2017)]

The RIC barrack attacks, especially the capture of posts, embarrassed the government, which began to lose its grip on rural Ireland. Rather than risk the humiliation of new IRA victories, the government simply evacuated all police barracks considered vulnerable. By the end of 1920, nearly half of the 1500 RIC stations in the country had been abandoned. Most were burned by the IRA within days of their evacuation, often in celebratory fashion, including hundreds torched on the night of the fourth anniversary of the Easter Rising. The government retreat from rural stations into larger towns and cities allowed the IRA to assert its control over much of the population. Already suffering from a popular boycott, police morale plummeted, and thousands of constables resigned from the force. During these same months, the court system also began to collapse, as a republican boycott brought civil cases and criminal prosecutions to a standstill.

Facing a major crisis in mid-1920, the British government militarized the situation. To bolster the beleaguered RIC, the government recruited unemployed ex-servicemen from England, Scotland, and Wales. Some became known as ‘Black and Tans’, while others were organized into the new Auxiliary Division of the RIC. Their arrival signalled the start of a government counter-offensive against the IRA. By late 1920, these new police had become infamous nationally and internationally for their use of reprisals against the civilian population. The Irish War of Independence had entered its most critical and controversial phase.

– This article by John Borgonovo was first published in the Irish Examiner on 24 March 2020 –