Civil War Fatalities in Cork

Civil War Fatalities in Cork

by John Borgonovo

Andy Bielenberg and John Dorney’s new forensic study of Civil War fatalities offers exciting perspectives to historians in the field. In my own specialty area of County Cork, the new Civil War figures allow for fascinating comparisons to Bielenberg’s companion digital project the 'Cork Fatality Register’. Undertaken with a different collaborator, Prof. James Donnelly Jr., its findings for the 1919-21 period help to contextualise civil war violence in the same area.

During the Irish War of Independence, ‘Rebel Cork’ was the most violent area of Ireland. Its total of 538 deaths far outdistanced other parts of Ireland in numerous categories. For example, in 1920-21, Cork accounted for 21 per cent (eight-six) of all Royal Irish Constabulary killed in Ireland; 21 per cent (forty-nine) of all British soldiers; and 40 per cent (seventy-four) of all civilians killed by the IRA as suspected spies or informers. Underscoring continued intensity, Bielenberg and Donnelly counted fifty-three further violent deaths in County Cork during the Truce period, which was a period of relative calm across the country with the notable exception of Northern Ireland.

At the outset of the Civil War, the Cork IRA dominated the anti-Treaty leadership, fielded the best armed and most experienced troops to face the National Army, and used Cork city as a ‘real capital’ to build up financial and military strength. However, once fighting broke out, fatal violence in Cork was far less pronounced than it had been in the War of Independence. The death figure for 1922-1923 dropped to from 538 to 215, or just under 40 per cent of the 1919-1921 total. The county lost its position in the vanguard of republican armed anti-Treaty resistance to neighbouring Munster counties, particularly Tipperary and Kerry.

-1052x685.jpg)

Fig. 1 Map showing the location and affiliation of the 215 combatant and civilian fatalities in County Cork between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923

Events and periodisation

While levels of violence diminished significantly, Cork was by no means peaceful in 1922-23. The number of overall deaths during the Civil War still put Cork among the more violent counties in the Free State. During the war’s ‘Conventional phase’, the National Army’s amphibious attack at Passage and the ensuing battle in the Cork city suburbs of Rochestown/Douglas on 8-10 August resulted in seventeen fatalities, which made it one of the deadliest episodes of the entire revolutionary period. Had the IRA not abandoned the city centre without a fight and acted instead as it had in Dublin, Limerick, and Waterford, that death toll would have been far higher. The remaining four months of 1922 (September to December) produced persistent fatal encounters between the IRA and the National Army, with civilians often caught in the crossfire. Bielenberg and Dorney count 127 fatalities in County Cork during those four months: thirty-four civilians, thirty IRA and sixty-three National Army soldiers. However, that level of violence was not maintained.

A key characteristic of the War of Independence in Cork was the bloody republican reprisals (and counter-reprisals) taken on Crown forces, including the shooting of off-duty troops and police, the taking of hostages, and the disappearance of intelligence officers. Similar responses were largely, if not entirely, missing in Cork during the Civil War. While the British forces in 1920-21 killed dozens of IRA members in custody (beyond official executions), far fewer IRA members died in similar circumstances during 1922-23 in Cork.

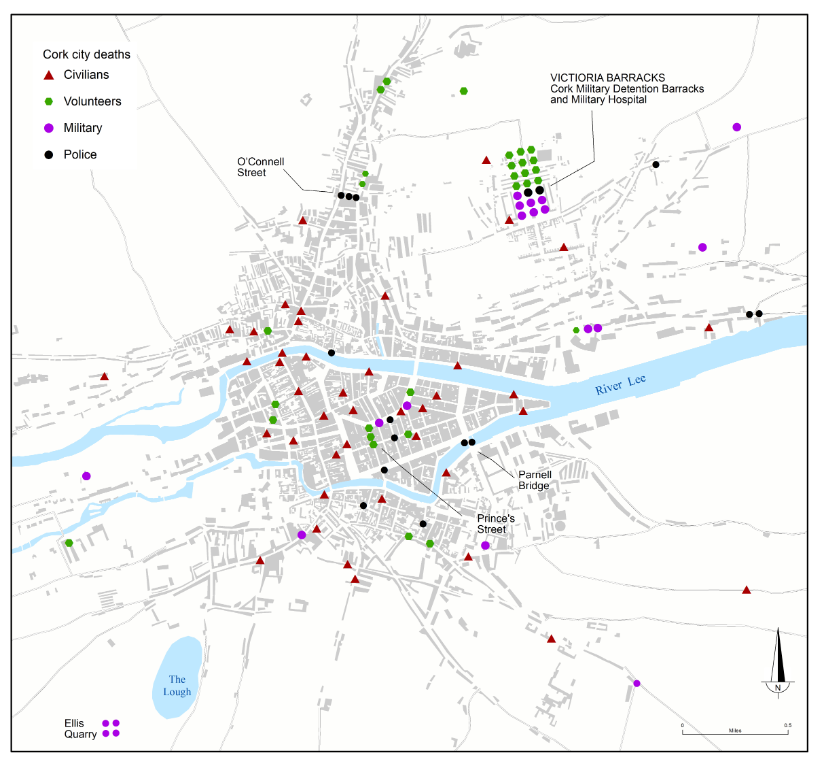

Fig. 2 Map showing the location and affiliation of combatant and civilian fatalities in Cork city during the Irish War of Independence, 1919-21

There were certainly horrific killings of IRA volunteers in Free State custody, such as Timothy Kennefick (tortured and shot by soldiers commanded by General Emmet Dalton), James Buckley of Macroom (killed as a reprisal for the deaths of six National Army soldiers at Carrigaphooca Bridge), and the roadside execution of three IRA Volunteers near Upton (Patrick Pierce, Daniel O’Sullivan, and Michael Hayes). But it also seems noteworthy that only one official Civil War execution occurred in County Cork (William Healy, 13 March 1923 in Cork Men’s Gaol), compared to thirteen during the War of Independence (eleven of those thirteen executed IRA Volunteers were from Cork). The departure from Cork of Major-General Emmet Dalton, who lobbied for executions and was personally implicated in the Kennefick killing, as commander of the National Army in County Cork during late 1922, may have also been a factor. He was replaced by Major-General Davey Reynolds, an ex-University College Cork student who had served with the IRA in Cork during the War of Independence. Whether or not Reynolds was a moderating influence on National Army conduct needs to be further explored.

Executions and transgressive killings by both sides often triggered cycles of reprisal and counter-reprisal, which in Cork had resulted in substantial numbers of deaths during the War of Independence. Overall, in Cork during the Civil War there seemed to be noticeably fewer of these types of killings, particularly when compared to County Kerry. While historians (including myself) frequently credit the Free State’s execution policy with breaking republican morale, the Cork case raises a different question: in certain areas did excessive official and extrajudicial killing by government forces harden republican attitudes and thereby create even bloodier conditions?

Fig. 3 A soldier wounded after the National Army landing on Passage West, County Cork being conveyed to the base hospital on board the Lady Wicklow [Image: National Library of Ireland, HOG54]

Anti-Treaty Morale

The Irish Civil War Fatalities Index underlines the collapse of the IRA offensive resistance in Cork during 1923. For the five months of August through December, 165 people died in the county. For the last five months of the war, January 1923 through May, only forty-six died. Probably the best-armed and most-experienced of the anti-Treaty forces, the Cork IRA remained lethal, with twenty-one National Army soldiers killed in this latter period compared to just six IRA members. That disparity of National Army to IRA deaths in Cork differed from the national trend during this time period, in which IRA deaths outpaced National Army ones. Significant IRA columns remained at large in Cork well after the May Dump Arms Order, such as those operating in the Kilbrittain and Bantry areas. The Cork IRA still had plenty of sting left in its tail, had it chosen to fight to the end.

Poor republican morale was more visible in County Cork than in other areas, which may be connected to the heavy involvement of the republican leadership in various peace initiatives. Senior Cork IRA officers had led the ‘Army Reunification Agreement’ in May 1922, while anti-Treaty TDs had also participated in a series of public peace meetings in early August 1922 to try to secure a national ceasefire.

Unofficial peace negotiations between National Army and IRA officers occurred in Cork during the autumn of 1922, while the Cork-led Neutral IRA organisation tried to broker a settlement in early 1923. The influential Cork IRA officer Liam Deasy, then the IRA deputy chief of staff and a former commander of the First Southern Division and Cork No. 3 Brigade, called for a ceasefire following his capture in January 1923. IRA prisoners in Cork Men’s Gaol and in other locations supported his appeal. The IRA’s Cork-led First Southern Division also began to pressure the IRA Executive for a ceasefire around this time. However, more work needs to be undertaken to better understand this dynamic at the local and national levels.

Geography, Civilians, and the National Army

The Irish Civil War Fatalities Project highlights a few regional hotspots in the county. Sustained and violent IRA resistance was apparent around the Macroom, Bantry, Bandon, and the Dunmanway areas. Anti-Treaty columns of hardened guerrilla fighters made these dangerous operational areas for the National Army. However, other areas that had been quite active in the War of Independence, experienced relatively few deaths. East Cork, for example, was considerably quieter, which is likely connected to the enlistment in the National Army of numerous experienced officers from the IRA's Third Battalion. Less obvious is the reason for the lack of lethal activity in large parts of North Cork (with the exception of Fermoy), which in 1919-1921 hosted the IRA’s highly aggressive and effective Cork No. 2 Brigade.

Cork city too was relatively quiet in the Civil War compared to the War of Independence. Using the Cork Fatality Register data, 123 people died violently in Cork city during the 1919-1921, compared to just forty-four in the Civil War (that latter figure excludes those killed in the Battle of Rochestown/Douglas, and fatalities where the person died in a city hospital but was mortally wounded elsewhere).

-907x754.jpg)

Fig. 4 Map showing the location and affiliation of the combatant and civilian fatalities in Cork city between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923

One reason for the decrease was that Cork city experienced far fewer IRA killings of suspected civilian informers, an outcome that was replicated across the county. Bielenberg andDorney identify at least five civilians executed by the IRA in 1922-23 in County Cork. However, that figure is a dramatic drop from the seventy-four civilian spy suspects killed across the county in 1920-21. British police and troops also killed scores of county Cork civilians in disputed circumstances throughout the War of Independence.

Though there were similar kinds of deaths at the hands of the National Army in Cork during 1922-23, there were substantially fewer of them. This is likely connected to the strong public support for the Free State war effort and the presence within the National Army of Irish (and Cork) soldiers who possessed significant local knowledge (see below). In this environment, the National Army seemed to have viewed the civilian population much more favourably than did the Crown forces in 1919-1921. For its part, the IRA also likely considered civilian collaborations with the Free State as far too numerous to control through targeted assassination (with some noticeable exceptions). Yet, there is still more research needed to understand the reasons for varying levels of public support for the Free State forces in different Free State locales.

Fig. 5 National Army troops in Pembroke Street, Cork, shortly after the retreat of the anti-Treaty forces in August 1922 [National Library of Ireland, HOGW 15]

When National Army forces arrived in Cork, they carried hundreds of spare rifles and armed and enrolled new soldiers on the spot, doubling their strength within a week. The deaths of some of those recruits are apparent in the Civil War figures. Bielenberg and Dorney have flagged the large number of Cork-born National Army dead, which totalled forty-three of 107 Free State fatalities in the county (40 per cent). Of those forty-three, just five had prior IRA service (11.6 per cent of the total), eleven were British Army veterans (25.5 per cent), and twenty-seven (63 per cent) had no military experience at all.

The small number of National Army dead with War of Independence IRA service is further seen by including the fifteen non-Cork soldiers, who together account for 14 per cent of the total. This provides additional evidence of the decisively anti-Treaty stance taken by the IRA in County Cork, and therefore suggests that rather than a conflict between pro and anti-Treaty elements of the IRA, the Civil War was a war between the IRA and an entirely new military force that included a small minority of War of Independence veterans. However, deeper exploration of the Military Service Pensions nominal rolls data in the Military Archives is required before we can draw more concrete conclusions.

Conclusion

In his two research projects, Andy Bielenberg has counted and detailed 806 deaths in County Cork in the entire 1919-1923 period. They occurred as part of Cork’s militarised resistance to two successive governments. However, the Civil War fatalities in Cork outlined by Bielenberg and Dorney are decidedly lower than the War of Independence total. It is therefore paramount for scholars to understand what did and what did not happen in Cork during the Civil War. Compared to the War of Independence in Cork, there were far fewer transgressive deaths, reprisal killings, deliberate killing of civilians, and official and extrajudicial executions of prisoners in the Civil War. A few elements have been identified as potential research avenues to be taken to better illuminate these outcomes. These include recognising the possible moderating influence of certain leaders (both pro- and anti-Treaty), the reasons for the apparent widespread public support of the Free State government, and the composition of the National Army and how it was perceived by friends, enemies, and neutrals alike.

It is clear that Bielenberg and Dorney have given us the tools to better understand the conflict at the local, regional, and national level. We will be analysing and interpreting their results of their research for a long time to come.

Additional Sources:

Andy Bielenberg and James Donnelly Jr, ‘The Cork Fatality Register, 1919-1923’, (digital publication: Cork, 2021), https://www.ucc.ie/en/theirishrevolution/collections/cork-fatality-register

Andy Bielenberg, John Borgonovo, Padraig Og O Ruairc, The men will talk to me: West Cork interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Cork, 2015)

John Borgonovo, The Battle for Cork, July-August 1922 (Cork, 2013)

John Borgonovo, ‘Cork’, in John Crowley, Michael Murphy, Donal O Drisceoil, and John Borgonovo (eds) Atlas of the Irish Revolution (Cork: 2017), pp. 558-568.

John Borgonovo, ‘Civic Administration and Economic Endowments in the Munster Republic’s “Real Capital”, July-August 1922’, Éire-Ireland, Volume 58: 3 & 4, Fall/Winter 2023, pp. 9-34.

Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1988

Padraig Og O Ruairc, ‘ “Spies and informers beware!”, IRA executions of alleged civilian spies in the War of Independence’, in Crowley et. al, Atlas of the Irish Revolution, pp. 433-436.

Daithi O Corrain and Eunan O’Halpin, The dead of the Irish Revolution (New Haven, 2020)

Charles Townshend, The Republic: The Fight for Irish Independence (London: Penguin Books, 2013)

Header Image: Republican prisoners being taken to Cork Jail, August 1922 [National Library of Ireland, HOGW 12]

Author’s Bio

Dr John Borgonovo is a lecturer in the School of History at UCC and is also co-editor of the Atlas of the Irish Revolution