Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

The Civil War in Sligo

by Frank Fagan

County Sligo experienced much higher levels of violence in the Civil War than it had in the War of Independence.

Two months before the Civil War began, just hours before Arthur Griffith addressed a pro-Treaty meeting, the opposing forces had already exchanged gunfire in the streets of Sligo town. A full-scale confrontation was narrowly averted on Easter Sunday 1922 but the fallout from this encounter was felt in Sligo for many months afterwards. Personal differences between Commandant General Billy Pilkington, Officer Commanding the Third Western Division IRA who advocated for a peaceful outcome on 16 April, and Brigade Commandant Frank Carty TD who proposed attacking the Free State forces in the town, would greatly influence events in the county as they unfolded after 28 June 1922.

Sligo’s First Fatalities

With the outbreak of fighting in Dublin, both pro-and anti-Treaty forces occupying buildings in Sligo town, decided that action needed to be taken. In the early hours of Saturday 1 July, Republicans under Pilkington began their planned evacuation of the town, setting the barracks alight in their wake. Free State forces seized the opportunity to increase their hold on the town and occupied more buildings. By 2 July, the IRA had established their headquarters at Rahelly House, eight miles north of Sligo town, near the coast and an ideal, secure location from which to operate. On the same day, Republicans under Carty’s command went on the offensive and captured the isolated Free State garrison in Collooney ten miles from Sligo town. It was an important victory, as the village was also home to a major rail intersection.

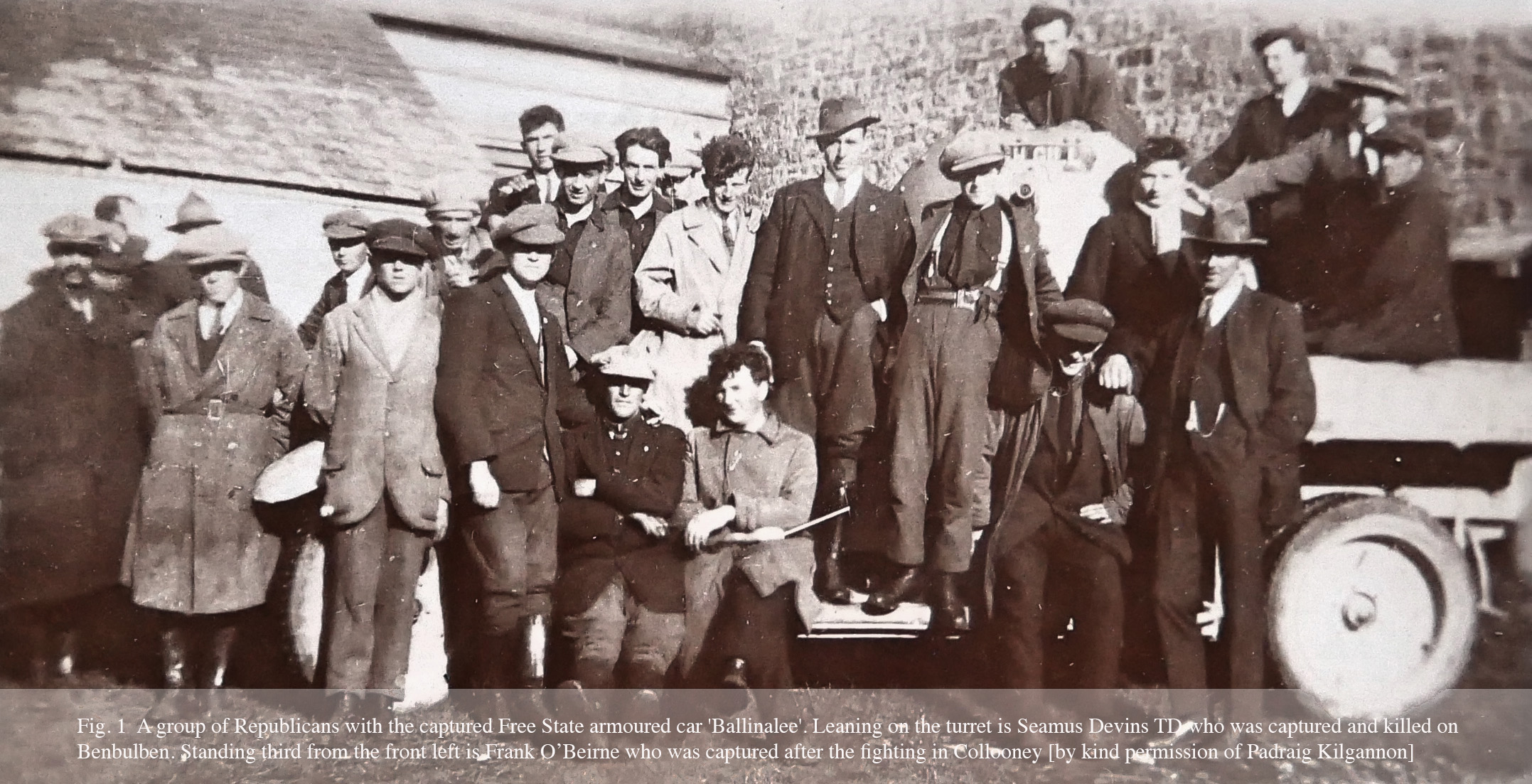

Monday 3 July saw the first civil war fatality in Sligo when Jason Byrne, a fifteen-year-old National Army soldier was shot dead by the IRA as he left Sligo Jail - a Free State garrison since 13 April. Within twenty-four hours, Martin Flannelly the first republican fatality, was shot dead during an attack on a Free State post in Gurteen. Four more members of the National Army were killed in the Rockwood ambush on 13 July, including Commandant Patrick Callaghan who had been a close associate of Major-General Seán Mac Eoin and had served with his Flying Column during the War of Independence. Apart from the loss of life, the National Army in Sligo had also lost a Rolls Royce armoured car, the ‘Ballinalee’, captured by the IRA in July, providing them with a mobile and lethal weapon for deployment against the National Army.

Fig. 2 Grave of Martin Flannelly [Courtesy of Frank Fagan]

The battle at Collooney

Having decided to attack the Republican garrison in Collooney, Major-General MacEoin sent an order for between 300 and 400 reinforcements from Athlone. Local Cumann na mBan member, Maria Gallagher saw the troop train arriving slowly in the darkness and stopping short of the station. She watched from a distance as National Army soldiers quietly disembarked, some of them armed with machine guns. As the soldiers surrounded the village, Gallagher cycled to Collooney Barracks to inform garrison commander Frank O’Beirne of their arrival.

The opening shots of the first major battle of the Civil War in County Sligo sounded at around 6.30pm on Friday, 14 July. Comdt-General Lawlor and Major-General MacEoin commanded the National Army in Collooney and their use of an 18-pounder gun to shell the village proved decisive. O’Beirne and twenty-three of his men surrendered at 9am on Saturday morning. After the loss of Collooney, the IRA evacuated Sligo’s urban centres to operate in columns as they had done during the War of Independence, while the National Army consolidated its hold on the towns by establishing new posts. The extent to which Republican forces remained a threat in large areas of Sligo was exemplified by Comdt-General Lawlor’s decision to land his troops in Enniscrone on 6 August rather than travel though the dangerous roads of west Sligo.

Turning Point: September 1922

An event in neighbouring County Mayo altered the course of the Civil War in County Sligo. On 12 September 1922, hundreds of Republicans from across counties Sligo and Mayo carried out a well-planned attack on the Free State garrison in Ballina. The Sligo Brigade area included parts of neighbouring counties, and the North Mayo Brigade area covered a portion of west Sligo from Templeboy to the Sligo/Mayo border.

The ‘Ballinalee’ armoured car led the attack, its Vickers machine gun pouring fire into the town before the National Army garrison and all of its weapons and fuel were captured by the IRA. Determined to deal with the Sligo republicans, Major-General MacEoin dispatched a large number of troops and the ‘Big Fellah’ armoured car to Ballina. On the 14 September, the National Army convoy headed north towards the mountainous border region between Sligo and Mayo and was ambushed at at Drumsheen just outside Ballina. Both armoured cars were involved in the fighting and the driver of the ‘Big Fellah’ was killed by a bullet wound to the head. National Army Brigadier Joe Ring was also killed during the ambush. Remarkably, the ‘Ballinalee’ made it safely from Ballina to Rahelly House by avoiding all the main roads. But its days were now numbered.

Following the fighting at Drumsheen, large numbers of National Army soldiers began to arrive in Sligo town with transport vehicles, an armoured car, ambulances and a field gun. On 19 September, troops under the command of MacEoin and Lawlor carried out large scale operations, with the focus of their attention on Rahelly House. Republican forces, including General Billy Pilkington and Brigadier Seamus Devins TD hurriedly vacated the IRA headquarters and sought cover in a wooded area nearby, which was shelled by the Free State field gun.

Conflicting accounts exist of the circumstances in which six Republicans were shot dead during the fighting. The bodies of Brigadier Seamus Devins TD, Divisional Adjutant Brian MacNeill, Captain Harry Benson, Lieutenant Patrick Carroll, Volunteer Thomas Langan and Volunteer Joseph Banks were left on Bunbulben Mountain by those who had killed them, reputedly after surrendering. At mid-day on 23 September the wrecked ‘Ballinalee’ was triumphantly dragged through the streets of Sligo town by Free State forces to the celebratory sounds of rifle and machine gun fire. It was placed outside the courthouse for the residents of the town to examine.

Fig. 3 The funeral of Seamus Devins TD, Patrick Carroll and Joe Banks, all killed on or near Benbulben on 20 September 1922 [by kind permission of Padraig Kilgannon]

The IRA in Sligo never fully recovered from the losses they suffered on 20 September, the last major civil war confrontation in County Sligo. Many of its members relocated to strongholds in the Ox Mountains to the south and Arigna Mountains to the west. In one final act of defiance, on the night of 10 January 1923, Sligo Republicans burned the main train station in the town and destroyed a large number of carriages and locomotives. Three months later, in early April 1923, over one thousand Free State soldiers took part in search operations of the Republican stronghold between Ballisodare and Ballina. It was the first time in the conflict that such a large force had entered the area.

When IRA Chief of Staff Frank Aiken issued his dump arms order on 24 May 1923, there were still some Republicans in Sligo who wanted to carry on the fight, but the order was complied with. The military hostilities may have officially come to an end, but the political ones could not be as easily buried as the weapons.

Sligo’s Civil War fatalities

The new research conducted for the UCC Irish Civil War Fatalities project can help us understand the extent to which the entire county was impacted by the conflict. Two incidents in 1922 - the Rockwood ambush in July and the fighting following the attack on Rahelly House in September - account for almost a quarter of the forty-four fatalities in Sligo between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923. The first three months of the conflict were the deadliest with twenty-seven fatalities, the remaining months of 1922 saw five Free State soldiers and two civilians killed. The new year would see six deaths between January and March, and the final two months of the war would add another four to the total.

The average age of those who died on the opposing sides in Sligo was eighteen years – testifying to the youth of the combatants. The youngest casualty, National Army soldier James Byrne, was fifteen and the oldest, seventy-six-year-old civilian Catherine McGuinness, was one of only two female fatalities in Sligo. The different categories in the UCC project show that National Army losses were the highest at twenty-one, followed by the IRA at fifteen and civilian deaths at eight. Detailing the circumstances surrounding each individual death in the research brings an added poignancy to this work.

The highest number of fatalities (seven IRA Volunteers and thirteen National Army soldiers) either died in action or as a result of wounds received in action). Three National Army soldiers were accidently shot by a comrade (one of them on the final day of the Civil War) compared to just one IRA death in similar circumstances. Another interesting comparison to come out of this research is that one third of the Free State fatalities were native to County Sligo, while thirteen of the fifteen IRA members killed were from the county. Six of the National Army soldiers had previously served with the IRA and two had served with the Crown forces, while thirteen of the republican dead had pre-Truce service with the IRA, one with Fianna Éireann and two with the Crown forces.

Of the civilian deaths, two were young cousins mortally wounded in the same incident. Henry and Philip Giblin died in Sligo County Infirmary of wounds received in crossfire during an IRA attack on a National Army position at Greenfort on 16 July 1922. The last civilian death to occur in Sligo during the Civil War, that of twenty-three-year-old farmer’s son, Edwin Williams on 16 April 1923, appears to have been motivated by a dispute over land rather than politics.

-812x714.jpg)

Fig. 4 Map showing the location and affiliation of the forty-four combatant and civilian fatalities in County Sligo between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923

Fatality Profiles

National Army: Private John Sweeney, 14 July 1922

At 6am on the morning of 13 July 1922, three Crossley Tenders and a Rolls Royce armoured car left the Free State garrison at Markree Castle to make the nine-mile journey to Sligo town. The vehicles carried twenty-eight men and three officers. As the convoy approached the townland of Rockwood ‘a devastating fire was poured in from the high ground on either side’. The gunfire ceased after an hour. Four members of the National Army died as a result of the Rockwood ambush, which had been planned and executed by Republican forces under the command of Sligo native Frank Carty. During the ambush, Private Sweeney received a number of bullet wounds to the head and body. He was taken to the County Infirmary where he was attended to by Dr McDonnell. He died of his injuries the following day and was buried in Sligo Cemetery, Sligo Town. (Research to confirm the place of burial was kindly provided by Kieran Gillen and Brian Scanlon)

IRA: Lieutenant Patrick Stenson, 13 March 1923

Lieutenant Patrick Stenson was twenty-eight years old when he was killed in National Army custody. He had joined the IRA in 1919 and was active during the War of Independence and Civil War. On 13 March 1923, he was part of a small group of armed Republicans near the village of Curry in County Sligo. He was a short distance behind the main group when they were suddenly surprised by the arrival of a lorry containing National Army soldiers. Stenson alerted his comrades to the danger; he was on the opposite side of the road from them when fire was exchanged between both parties. Isolated from the main body of Republicans and having exhausted all his ammunition, Lieutenant Stenson surrendered and was disarmed. The following morning his body was returned to his family home by Free State forces. He had suffered a number of gunshot wounds.

Fig. 5 Lieut. Patrick Stenson [by kind permission of Aiden Marren]

Civilian: Catherine McGuinness, 2 April 1923

Catherine McGuinness was a seventy-six-year-old widow who lived in an isolated mountainous area of west Sligo in the townland of Carns, Culleens. She was at home with her sons James and Owen at 11pm on the night of Sunday 1 April 1923 when an armed member of the Republican forces, who appears to have been known to the family, called to the house. He and the McGuinness brothers consumed a quantity of poteen and, at some point during the night, an argument broke out. There was a physical struggle between them which continued outside the house. The Republican then opened fire. As Catherine McGuinness lifted the bolt on the front door to allow her son back in, she suffered a catastrophic gunshot wound and was dead within seconds.

Main Sources

James Bonsall, Marion Dowd, Robert Mulvaney, The Six, The Lives and Memorialisation of Sligo’s Noble Six, (Glencar Press, 2022)

Michael Farry, The Aftermath of Revolution Sligo 1921-23, (Dublin, 2000)

Michael Hopkinson, Green Against Green, The Irish Civil War, (Dublin 1988)

Joe McGowan, Even the Heather Bled, (Sligo, 2021)

Irish Military Archives, Military Service Pensions Collection, 2D175, James Byrne; MSPC DP3522, Martin Flannelly; MSP34/55995, Maria Gallagher; MSPC 2D392, Thomas Ingham; MSP34/33559, John Brennan; MSP 345687, Frank Carty; MSPC DP7025, Patrick Stenson; MSP34/64176, Maria Marren; MSPC SP. G. 16, James McGuinness.

Author’s Bio

Frank Fagan is a psychotherapist and historian with an MA in local history from UCC. He has a particular interest in the legacy and aftermath of the Civil War in Sligo, and how memory was preserved within the families directly impacted by the violence of a century ago.