Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

The Civil War in Mayo

By Joost Augusteijn

The conflict as fought out in County Mayo during the Civil War deviated somewhat from the pattern and characteristics of other areas. In Mayo, actual fighting had come late in the War of Independence, but the relatively successful foray into ambushing in 1921 imbued the Mayo IRA with optimism. The large influx of new members during the Truce gave them a strong belief they could successfully continue fighting.

Indeed, very few Mayo IRA officers went pro-Treaty, the most senior being Joseph Ring. As a result, there was essentially no National Army presence in Mayo when hostilities broke out on 28 June 1922, and the thousands of IRA men had been able to prepare themselves. Most roads and railway lines were blocked and armaments were improved, including home-made armoured cars and explosives. As a consequence, Mayo was, at the beginning of the Civil War, widely considered the major stronghold of the anti-Treaty IRA in the West.

The outbreak of hostilities

Initially, the outbreak of hostilities had little effect on Mayo. The National Army did not immediately attempt to take control of the county. The few casualties in the first month of the Civil War included one man shot by the IRA in Kiltimagh for attempting to recruit for the National Army, and Mayo men killed while assisting in the defence of neighbouring counties against the advancing army. It was almost a month before the army moved into east Mayo, which was relatively lightly defended by the IRA who had their strongholds in Castlebar and Ballinrobe. A concerted attack to take Claremorris was initiated on 23 July, followed by a surprise naval landing in Westport the day after.

The National Army had anticipated a tough battle in Mayo, but experience elsewhere had made clear to the IRA the difficulty of defending buildings against the National Army’s superior firepower. They ceded control of the towns without opposition, but attempted to destroy the major buildings they had occupied so they could not be used by the army. By the end of July, all Mayo towns had been vacated. Large sections of the local population welcomed the arrival of the Free State troops after weeks of minimal contact with the outside world.

Fig. 1 Photograph of the National Army featuring Joe Ring [Courtesy of Michael Ring TD]

Restored IRA confidence

The swift take-over of the towns gave the impression that the Civil War in Mayo was as good as over by early August, but the anti-Treatyites still controlled most of the countryside where it was too dangerous for the National Army to engage them directly. In contrast to the open fighting in the southern counties, the Civil War in Mayo settled almost immediately into a guerrilla type struggle, the features of which hardly changed and even extended beyond the formal end of the Civil War.

The IRA made its presence known by nightly attacks on National Army posts and police patrols in the towns. Occasionally, they organised small diversions in the countryside to draw out the army garrisons and engage them in the open. This was rarely effective, and most serious engagements developed when the two sides met accidently.

Minor successes and the hesitancy of the National Army to engage the guerrilla fighters soon restored anti-Treatyite confidence. Already, in late July they began to reoccupy some of the minor towns that were weakly garrisoned by government forces. Some army patrols were also forced to surrender, including a fifty-strong detachment in September. The IRA’s biggest coup was the taking of Ballina on 12 September, after which they released the captive soldiers and left with a large store of weapons and money from the local bank. The subsequent fight between the National Army’s advancing support troops and the IRA retreating to the Ox Mountains was the largest extended military confrontation of the entire Civil War in Mayo. The casualties were limited but included the senior army officer, Joe Ring. The biggest success for the IRA came in an ambush at Glenamoy in northeast Mayo meant to divert troops away from the Ox Mountains in which they killed seven soldiers.

Fig. 2 South Mayo flying column

The turning tide

Although the Mayo IRA continued their campaign in the months that followed, the fighting eventually began to take its toll. A shortage of ammunition and reliable explosives limited their ability to stage sustained attacks. Losses, mostly as a result of mounting arrests, also depleted their forces. National Army drives rounded up hundreds of IRA men often with their weapons, including divisional commanders Tom Maguire and Michael Kilroy in the autumn of 1922. Despite suffering from poor discipline and a dearth of supplies, the National Army slowly gained an advantage over the Mayo IRA. An important element in this was the replacement of Tony Lawlor with Michael Hogan as GOC of the Claremorris Command of the National Army in January 1923. He introduced more rigid discipline and effective tactics, which also played a part in turning the tide.

Maintaining Resistance

Morale sustained among the republican forces notwithstanding continuing losses, the excommunication of IRA members by the Catholic Church in October 1922 and the government’s Army (Special Powers) Resolution which introduced the death penalty in late September. The amnesty introduced at the same time was only taken up by a handful.

IRA Active Service Units (or flying columns) with hundreds of members still operated in the north of the county, and small groups of activists in the south engaged in a combination of small and large-scale attacks. All generally without inflicting casualties. Members of the new police force (the Civic Guard), as well as supporters of the Treaty and opposing politicians more frequently became victims of IRA violence. Maybe because of the IRA’s depleting ranks, a number of women in uniform were arrested in 1923. While April saw a certain tapering off of violence, the IRA still staged attacks on Bonniconlon and Enniscrone barracks in the Ox Mountains. On 24 April the Irish Times had to acknowledge that Mayo was one of the few remaining counties not completely in the hands of government forces.

The ceasefire called by the IRA Army Council on 30 April was not respected by the National Army, which continued to round-up republican men and women, nor by a large share of the IRA in Mayo who also refused to accept the instruction on 24 May to dump arms. They continued to engage in small operations and even an occasional ambush. As a result, small-scale attacks, arrests and even killings continued in the subsequent months.

Analysis of deaths

There were relatively few Civil War fatalities in County Mayo, despite the intensity and duration of the fighting. Fourteen IRA volunteers and forty-five National Army soldiers were killed in the county between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923, of which only five IRA men and twenty-eight National Army men were killed in action.

There was actually never more than one IRA man killed in a fight in a single month, and most of the deaths in action occurred in the first months of the Civil War. In contrast, National Army fatalities in combat were spread out over the period. Twenty-five of them fell during 1922, with the last one shot in February 1923. Most were killed in the fighting surrounding the taking of Ballina in September with another five in November during a single clash near Newport. Although the conflict endured, no one was killed in action in Mayo during the Civil War after March. No Cumann na mBan members were killed and only one sixteen-year-old member of the republican youth group, Na Fianna Éireann. He was knocked down by an army lorry.

A specific and continuous feature of National Army fatalities was the large numbers killed accidentally. Of the seventeen accidental deaths in Mayo, fifteen occurred as a result of the unsafe handling of arms. One man was deliberately killed by a fellow soldier and one more died of ill health attributable to National Army service. There were more diverse causes of death on the IRA side. Two men were accidentally shot, four were killed while in National Army custody and two more died of ill health.

-879x763.jpg)

Fig. 3 Map showing the location and affiliation of the seventy-three combatant and civilian fatalities in County Mayo between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923

Civilian Deaths

Both sides used a small amount of deadly force against civilians, only very rarely with intent. There were thirteen civilian casualties in total, six of whom were killed accidentally or in crossfire. The first deliberate killing of a civilian that can be attributed was of Christopher Farrell, a commercial traveller, who was shot by the IRA in a case of mistaken identity in January 1923. Another three civilians were killed by the IRA in April; one as an alleged spy, one Free State supporter was killed when shots were fired into his home in Ballina, and an employee of the paymaster general was killed during an ambush. The National Army shot one man who obstructed a raid and was responsible for another civilian death when they fired at some rioters. The final casualty was shot during a raid by ‘men unknown’.

The focus on the county boundaries as units for counting casualties obscures how Civil War violence moved freely across counties. Michael Kilroy’s column also operated in County Galway, taking Clifden in a major operation in September 1922, and operations in North Mayo were influenced by events in Sligo. The first IRA casualty, T.J. Prendergast from Louisburgh in County Mayo, was killed when his lorry collided with an obscured IRA roadblock in Galway.

A number of Mayo men, including the younger brother of Tom Maguire, were executed in County Galway, while some Mayo casualties also fell in fighting outside the county. Other fatalities occurred before or after the period defined as the Civil War but were nevertheless associated with it. While the hostilities formally ended with the Dump Arms Order in May, the fighting, particularly in Mayo, continued, more people died. The last National Army soldier killed in action was on 31 August 1923, and Private Thomas Lackey died on 22 July 1924 of wounds sustained in September 1922. Two IRA men, including a senior IRA officer sent to reorganise local units, were killed in June 1923.

Fatality Profiles

National Army: Joe Ring

Joseph (Joe) Ring was born in County Galway on 17 August 1891. His father Michael, a native of County Kilkenny, was a RIC sergeant in his mother’s native Westport. Joe was raised in Westport and joined the Irish Volunteers in 1915. In the wake of the Easter Rising, he was arrested and interned. He subsequently became one of the most prominent republican activists in west Mayo. In 1918 he was arrested and sentenced to six months imprisonment with hard labour. After his release he was involved in the killing on 29 March 1919 of the resident magistrate responsible for his sentence, John Charles Milling, who became the first casualty of the War of Independence in Mayo. Ring subsequently became the vice-commander of the West-Mayo Brigade and flying column. Following the Truce he was appointed Liaison officer with the British authorities. After the Treaty he chose the pro-Treaty side. During the Civil War he served as Brigadier General of the National Army and was instrumental in the setting up of the Civic Guard. He was killed on 13 September 1922 in the Ox Mountains during the pursuit of the republican force that had taken Ballina the day before.

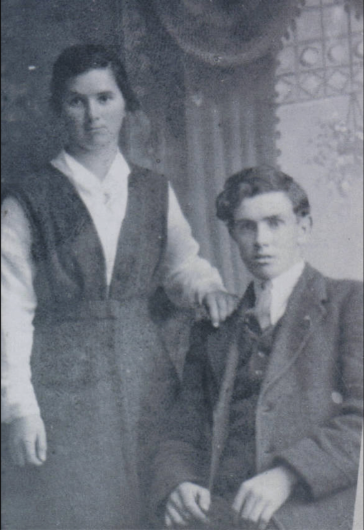

Fig. 4 Joe Ring [Courtesy of Michael Ring TD]

IRA: Patrick Mulchrone

Patrick Mulchrone born 29 January 1897 in Westport was shot by National Army troops in Aghagowla between Westport and Newport on 1 November 1922. He died two days later. Patrick had joined the Volunteers during the War of Independence and acted as a Transport officer in Castlebar. As a licensed driver he had been able to buy his own car which allowed him to provide services for the IRA. When the National Army entered the town in July 1922, he organised a boycott among his fellow drivers, causing his motor car to be commandeered. When he was shot he was in the house of Patrick Gallagher a known supporter of the IRA, who lived in the former Brockagh RIC barracks. The circumstances of Mulchrone’s death are disputed. What is clear is that there was a round up by about thirty National Army soldiers in this well-known republican area. They claimed they were being fired at from Gallagher’s house and simply retaliated with grenades and rifle fire. The inhabitants stated the officer in command, Joe Ruddy, who knew Mulchrone, came into the house and, unprovoked, shot the unarmed Mulchrone.

Fig. 5 Patrick Mulchrone

Civilian: Christopher Farrell

Christopher Farrell born 1873 and killed on 17 January 1923 was a commercial traveller for Sir John Power and Sons whiskey distillers in Dublin, where he lived at 6 Waterloo Road. He was a frequent visitor in many parts of Ireland including Mayo. In January 1923 he stayed in Claremorris from where he visited Swinford with a fellow commercial traveller, Edward Harris. On the way back, the car he was travelling in ran into a road block at Kinaffe close to Kiltimagh consisting of stones taken from the bridge parapet. The driver safely negotiated the bridge which had a way through for cars, but when he drove on they were fired upon. Farrell was killed by a shot in the chest and Harris was wounded. When the car came to a stop, they were approached by about twenty young men in pale green trench coats armed with rifles who claimed they had called upon them to stop and only fired to make them halt. Farrell was subsequently attended by a priest in Knock and interred in Glasnevin on 19 January 1923.

Author’s Bio

Dr. Joost Augusteijn is senior lecturer at Leiden University, the Netherlands. He has previously held positions at various universities in the Netherlands and Ireland. He is the author of From Public Defiance to Guerrilla Warfare: The experience of ordinary Volunteers in the Irish War of Independence (1996), Patrick Pearse: The Making of a Revolutionary (2010) and the upcoming The Irish Revolution, 1912-23. Mayo (1923), as well as editor of several volumes.