Research Findings

The Irish War of Independence in geographical terms was defined by certain regions in Ireland that experienced very high levels of violence and by other areas (far more typical) with relatively limited degrees of violence. Death provides the most quantifiable measure of extreme violence; it was generally noted by the military protagonists, in state records, by relatives of the victims, in burial records, and by local and national newspapers, so that most fatalities can be successfully captured from the host of sources available. Recent research has revealed heavy concentrations of fatalities in the vicinity of the three major urban centres on the island (Belfast, Dublin, and Cork), making case studies of these three epicentres worthy of more detailed scrutiny. In the case of Cork violence extended to many parts of the surrounding county and did so to a greater degree than in the hinterlands of the two larger cities. In absolute terms County Cork recorded the highest number of deaths among all counties in Ireland as well as somewhat more than one-fifth of all fatalities on the island during the War of Independence.2 This makes Cork an especially important case study.

Peter Hart, as part of his pioneering 1998 thematic study of the revolution in Cork, was the first scholar to enumerate all conflict-related deaths in the county between 1917 and 1923. Unfortunately, he did not publish a list of the names of victims (though scores of those killed appear in his text), so it is impossible to verify many of his findings concerning all of those killed.3 Our enumeration of deaths here (539 in total) for the War of Independence alone is not too far from Hart’s aggregated findings for this period, although our definitions of conflict-related fatalities and the balance between groupings are slightly different from his, since (among other reasons) he did not include fatal military accidents. Since Hart published his findings, access to a range of new sources has become available (online in particular).

Barry Keane, using slightly different criteria, published a volume entitled Cork’s Revolutionary Dead, 1916-1923 (Cork, 2017), returning 477 fatalities for the War of Independence period (up to the Truce), but this included some deaths outside Cork such as Alderman Tadhg Barry who was killed at Ballykinlar Detention Camp, or George Tilson who committed suicide on a London-bound train. The first version of our fatality index recorded 528 deaths for this period when it was published online very shortly before Keane’s volume appeared. More recently, Eunan O’Halpin and Daithí Ó Corráin in their book The Dead of the Irish Revolution (2020) slightly raised the figure for this time frame (from the beginning of 1919 up to the Truce) to 534 for County Cork. But we are not in accord with some entries in this volume which would reduce this number; for example, we don’t believe that William Shields was captured and killed in Cork in the later stages of the War of Independence as claimed; Volunteer Frank Hurley was counted twice (once as an unknown victim killed on the same date). An unknown spy killed by the 5th Battalion of the Cork No. 1 Brigade requires further verification as this entry may also be a case of double counting. Furthermore, though initially we included ex-RIC man Jeremiah George Quill, abducted from Kilgarvan, we now have reason to believe he was not killed, but emigrated and died in the late 1970s in New Zealand.

We have now revised our original estimate upwards after taking account of new research. But this still remains a work in progress that can be revised by means of onging public engagement with our Cork Fatality Index. We have removed one death from our last list when evidence was brought forward that this fatality occurred in another county (thanks to Dara McGrath for this correction). We have clarified other entries as new information has come to light, for example, by naming two victims listed as unidentified in our first list. More evidence has been disclosed on the relatively higher number of victims who were disappeared by the IRA in County Cork during the War of Independence period in particular. (See Andy Bielenberg and Padráig Óg Ó Ruairc, ‘Shallow Graves: Documenting and Assessing IRA Disappearances during the Irish Rebellion’, Small Wars and Insurgencies, 32:4-5 (2021): 619-41.)

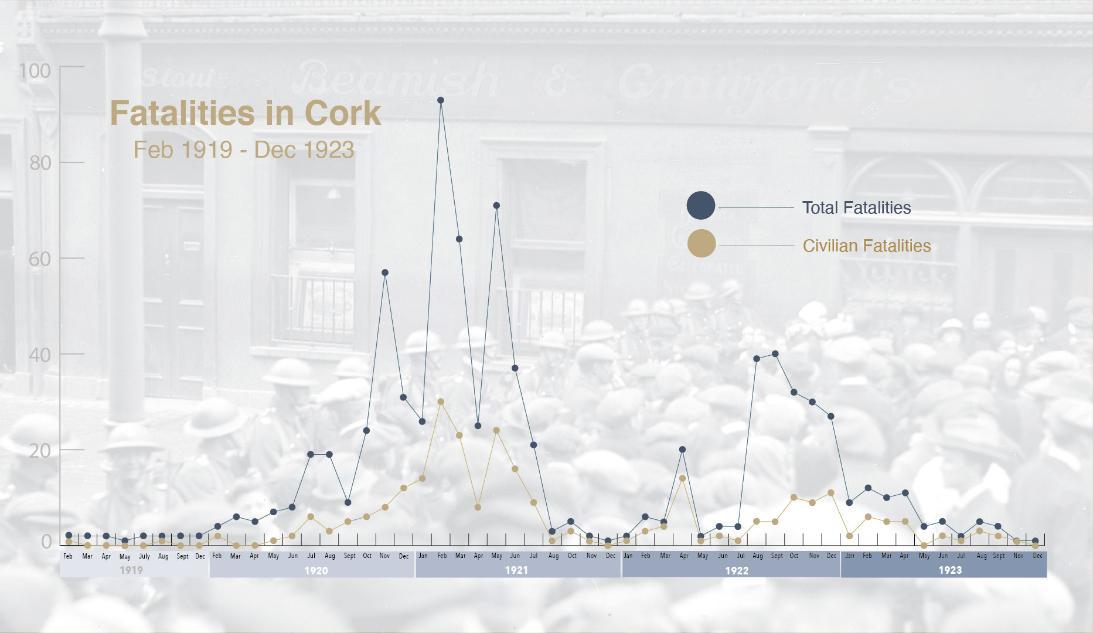

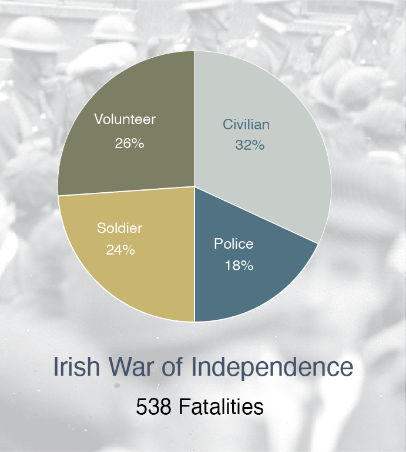

The pie chart of fatalities in the county reveals that civilians accounted for just under a third of all fatalities in the War of Independence, thus constituting the largest category of victim. This was partially due to the relatively greater commitment of the Cork IRA to ruthlessly targeting suspected spies and informers than the IRA in other counties. It also reflects counterinsurgency measures by crown forces in which civilians were killed, such as shootings at road blocks, etc. But despite this high toll among civilians it should be noted that civilian fatalities in County Cork were lower than in Dublin, and markedly lower than in Antrim, where civilian sectarian killing constituted the dominant category of victim. (For comparisons with County Antrim, see O’Halpin and Ó Corráin (2020), 548.) In County Cork, by contrast, the majority of victims in the War of Independence were the military protagonists, with crown forces accounting for 42 percent of all victims, and volunteers for 26 percent. (See pie chart above).

Fatalities in Cork during the Truce

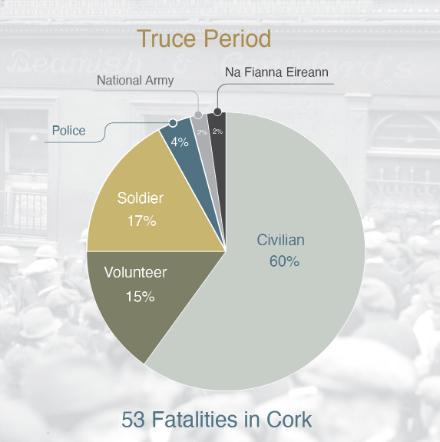

During the Truce fatality levels in County Cork declined dramatically relative to those experienced during the War of Independence. Nonetheless a low level of killing continued, with a notable rise in the civilian share of fatalities, which rose to 60 percent of the 53 persons who lost their lives in this window.

During the Truce fatality levels in County Cork declined dramatically relative to those experienced during the War of Independence. Nonetheless a low level of killing continued, with a notable rise in the civilian share of fatalities, which rose to 60 percent of the 53 persons who lost their lives in this window.

These civilian deaths included those occurring in the ‘Dunmanway massacre’, in the closing stages of the Truce in late April 1922, when 13 Protestants were shot dead in west Cork by anti-Treaty IRA members without local leadership approval. These sectarian-reprisal attacks, which took place during the final stages of British withdrawal, were quite exceptional in ferocity as a response to the death of a single Volunteer. Though the attacks shook the confidence of the west Cork Protestant population, they were not repeated. It was only after the Civil War got underway that fatalities again began to climb.

Fatalities in Cork during the Civil War

The Civil War erupted in Ireland with the notorious attack on 28 June 1922 by British-armed forces of the Free State Provisional Government on the small anti-Treaty IRA garrison briefly holding the Four Courts in Dublin. In County Cork, however, few deaths occurred in July of that year. There were only four conflict-related fatalities that month along with three in June. The bloodletting in County Cork really started early in August, when the new and rapidly mobilising National Army initiated its successful three-day campaign to capture Cork city by landing 450 soldiers under General Emmet Dalton at Passage West on the second Tuesday of the month (8 August). Many of the 39 recorded fatalities in August occurred in Dalton’s line of march towards the city, with sharp if short engagements between Free State troops and anti-Treaty Republicans (IRA) occurring around Passage West, Rochestown, and Douglas. Altogether, at least 11 killed were National soldiers, while a minimum of 5 killed had fought with the IRA in these engagements.16 The subsequent landing of National soldiers in much smaller numbers (180 men) at Union Hall on the far western side of the county, and their progress eastward, led to further fatalities, especially at Bantry. Indeed, August was a deeply depressing month for leading Free State military officers with Cork connections and for the government in Dublin: among the fallen were Lieutenant Commander Edward Cregan (killed on 20 August at Curraghs near Kanturk); Captain Hugh Thornton Jr (killed on 27 August by the accidental discharge of a comrade’s rifle while travelling between Bantry and Skibbereen); and still more tragically, National Army Commander-in-Chief Michael Collins himself (killed on 22 August in an IRA ambush at Béal na mBlath near Clonakilty). Throughout the last quarter of 1922 fatalities remained very high, with 128 conflict-related deaths.

Fatalities declined steeply beginning in January 1923 and remained low for the rest of the Civil War and its aftermath down to the end of the year. Only 46 more deaths occurred in the five months from January to the end of May 1923, and the total for the rest of that year reached only 18. In short, extreme violence in County Cork during the Civil War was more concentrated in the last five months of 1922, when almost 60 percent of all fatalities took place. (This calculation includes all known deaths from June 1922 through December 1923; alternatively, if the period were limited to the months of June 1922 through May 1923, the corresponding figure would somewhat exceed 60 percent.)

Fatalities declined steeply beginning in January 1923 and remained low for the rest of the Civil War and its aftermath down to the end of the year. Only 46 more deaths occurred in the five months from January to the end of May 1923, and the total for the rest of that year reached only 18. In short, extreme violence in County Cork during the Civil War was more concentrated in the last five months of 1922, when almost 60 percent of all fatalities took place. (This calculation includes all known deaths from June 1922 through December 1923; alternatively, if the period were limited to the months of June 1922 through May 1923, the corresponding figure would somewhat exceed 60 percent.)

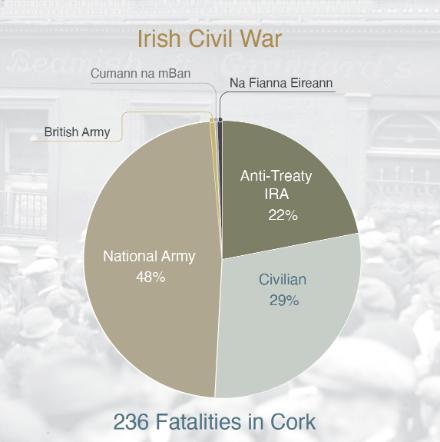

An examination of the 236 Civil War deaths in terms of the status of the victims killed reveals that somewhat fewer than a third (29 percent) were civilians, whereas more than two-thirds (71 percent) were either National troops or IRA men. Civilian deaths during the Civil War in County Cork, calculated as a proportion of total fatalities during that conflict, were only a few percentage points lower than the toll of civilians killed during the War of Independence in Cork, though of course many more civilians had been fatal victims in 1919-21. What is rather surprising about these results is that so many Cork civilians died in 1922-23 even though the number of suspected civilian spies executed by the IRA was much fewer than in 1919-21, and even though crown forces, which in the War of Independence had been responsible for a relatively high proportion of civilian deaths, were now completely removed from the scene.

Neither the IRA nor the National Army could claim that they went to great lengths to avoid civilian deaths. John Dorney’s assertion that the IRA’s ‘treatment of civilians was considerably worse than the National Army’s in County Cork’ during the Civil War requires some qualification.17 It is true that on a greatly reduced scale as compared with the War of Independence, the IRA continued to execute suspected civilian spies, killing fewer than 10 persons for this reason and also fatally wounding on his city doorstep the prominent Cork businessman William Goff Beale on 16 March 1923 in reprisal for the Free State government’s execution of republican prisoner William Healy three days earlier. In slightly more than two-dozen instances, however, the parties responsible for civilian fatalities either were completely unknown or had faced off (under the flag of the Free State or the Republic) in military encounters in which the exchange of gunfire resulted in the deaths of unfortunate civilians not targeted by either side. Admittedly, in some of these ‘crossfire deaths’ the Cork city IRA had initiated grenade or gun attacks on National forces in circumstances—‘busy shopping streets’—that posed an imminent threat to the lives of innocent civilians and resulted in needless fatalities. But it is incorrect to say that the National Army killed ‘considerably fewer civilians’ in County Cork than their Civil War opponents.18 In fact, the number of civilian deaths attributable to one side or the other in the conflict was roughly the same—but with the number of fatalities attributable to the National Army (17 or so) slightly exceeding those for which the IRA was responsible.

A striking feature about Civil War combatants in County Cork is that National Army fatalities (at 114) were well more than twice as high as those of the IRA (at 53). In part this disparity was the result of a much higher death rate among National troops in firearms and other accidents than among IRA fighters, almost certainly because the National Army took more proactive offensive action, but also because its recruits had often received little or no firearms training prior to their being rushed into active service.19 Given the speed with which National forces gained the upper hand in the county and then consolidated their military advantages, the imbalance in deaths suggests that—despite all that has been said about the reluctance of the Cork IRA upon entering the conflict, about its lack of commitment to the fight, and about its poor showing against superior forces and arms—the undermanned and under-resourced Cork IRA still managed to inflict punishing casualties on its more numerous and better-equipped opponents.20

Drastic punishment of another kind was evident on the sidelines of the battlefield. Military atrocities were, if not commonplace, all too common. In this regard County Kerry was the worst plague spot,21 but Cork certainly exhibited similar tendencies on a smaller scale. Long after it occurred, what transpired suddenly near Carrigaphooca Bridge near Macroom on 16 September 1922 etched itself deeply into the minds of local inhabitants and many others who had no connection with the place. An improvised explosive device (commonly called a ‘trap mine’) laid by the IRA in the roadway detonated that Saturday with great force, killing six National Army soldiers and fatally wounding a seventh (the high-ranking Colonel Commandant Tom Keogh) as they attempted to remove it. As the historian Sean Boyne has noted, ‘It was said that human flesh hung from thorn trees in the vicinity and that body parts were being found up to two weeks after the massive explosion.’22 Some of Keogh’s Dublin comrades—like Keogh, close friends of Michael Collins—took almost immediate revenge by killing elderly local man James Buckley and dumping his corpse in the crater made by the explosion. (See entries under this date in Cork Fatality Register.)

This particular set of atrocities was quite untypical for County Cork during the conflict, but its mutual bitterness was reflected in lesser atrocities, such as the killing of IRA Captain Timothy Kenefick at Nadrid near Coachford on 8 September 1922, apparently by Free State soldiers under General Dalton’s command. ‘Shot while attempting to escape’ was one contemporary cover story in this instance—a chilling echo of the claim often made by British forces about dead Volunteers during the War of Independence, but most likely as empty in 1922-23 as it had been earlier. Other atrocities of this ‘lesser’ kind occurred, for example, at or near Upton on 4 October 1922 when Free State troops participated in the killing of three IRA prisoners who had surrendered to them; Tom Barry later charged that a National Army chaplain (no less) had carried out their execution. Equally alarming were the fates of three civilians (John Desmond, Patrick Murray, and teenager Charles O’Leary) after National troops forced them and others (all wrongly suspected of IRA activity) to engage in clearing mines at Farnalough near Newcestown on 3 February 1923; the inadvertent detonation of a ‘trigger mine’ there ended three lives and wounded six other civilians in this case. (See entries under these three dates in Cork Fatality Register.) John Dorney has pointed out that Free State soldiers perpetrated ‘far fewer reprisals in Cork than were carried out by National army troops in counties such as Dublin and Kerry’, and he credits ‘the relative restraint of pro-Treaty forces in Cork’ largely to ‘the moderation of locally raised Cork troops’.23 But one might object that nearly half of the National soldiers who served in County Cork during the Civil War were not locally raised (the precise figure in October 1922 was 45 percent),24 and that we probably do not yet know the full extent of ‘lesser’ atrocities on both sides.

What our record of Civil War fatalities establishes beyond doubt is that Cork was the scene of a larger toll of fatalities than that of any other Irish county except Dublin. Earlier estimates of these conflict-related deaths in Cork, such as those of Peter Hart (180), Barry Keane (208), and John Dorney (220),25 have been short of the total (236) which our research has confirmed for the period from 1 July 1922 to 30 December 1923. Even these new figures for County Cork, however, should be regarded as minimum ones that are likely to increase as our research is subjected to the scrutiny of other historians and the wider public.

Conclusion

The trauma of death for civilians and protagonists alike in Cork left its deepest mark during the War of Independence, which accounted for 65 percent of conflict-related fatalities in the county during the Irish Revolution—the bulk of all fatalities. So far, then, some 827 fatalities have been recorded for the Irish Revolution in the county, and it is highly likely that this number will rise as further information comes to light. The County Cork deaths certainly constituted a notable share of all fatalities during the Irish Revolution—something approaching a fifth of the total for Ireland as a whole.