In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

UCC’s Dr Helene O’Keeffe examines the events that led to the declaration of Martial Law in December 1920 and the impact of the new measures in the proclaimed areas.

The streets of Cork were quiet on St Patrick’s Day, 1921. It was a subdued city, blackened by fire and patrolled by British soldiers and armoured cars. An atmosphere of menace prevailed as pedestrians were held up and searched after High Mass and shots were heard in the Grand Parade and near Patrick’s Bridge in the afternoon. The use of motor cars and bicycles was restricted, homes and businesses were liable to be searched or even destroyed as part of an official reprisal, and anyone caught on the streets after the 9 pm curfew was breaking the law. It had been three months since the declaration of martial law in the southern province.

With the outbreak of IRA violence in 1919, the Military Command in Ireland advocated placing the courts and the civil authorities under the control of the Army. In the face of IRA insurgency, they argued, martial law would unify military and police control and increase efficiency by trying suspects by court martial. The difficulty for Lloyd George’s coalition government was that to involve the military would be to admit that a state of war existed between the IRA ‘murder gang’ and the United Kingdom. As the prime minister asserted in April 1920, ‘you do not declare war against rebels’. This is why, in 1919 and 1920, the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) rather than the substantial British Army garrison in Ireland was tasked with quashing the challenge to the British authority.

In the face of intensifying IRA activity in 1920, the government decided to strengthen the besieged RIC rather than declare martial law in Ireland. British ex-servicemen supplemented the police force and the enactment of the Restoration of Order in Ireland Act in August extended their powers of search, arrest and internment without trial. These measures, as well as the unofficial reprisals and collective punishments meted out by the Crown Forces, failed to frustrate IRA violence, which escalated in last months of 1920. Staggered by events of Bloody Sunday and the Kilmichael Ambush in November, the government could no longer convincingly portray the conflict as a police action. This was a war and a new more stringent policy was required to deal with the IRA.

The most immediate official response on 22 November was to sanction the widespread arrest and internment of ‘all known officers’ of the IRA. Within a week of Bloody Sunday, over five hundred arrests had been made across the country. As the Better Government for Ireland Bill entered its final stage in parliament in December, the government was aware of the pressing need to restore law and order in Ireland to facilitate elections to the newly created parliaments of Northern and Southern Ireland. Added to this was the mounting national and international criticism of an Irish policy which allowed brutal unofficial reprisals on the civilian population by undisciplined RIC militias. Despite the misgivings of some cabinet members, the voices in favour of sterner action prevailed and it was agreed, in December 1920, to introduce martial law – at least in the more lawless regions of Ireland.

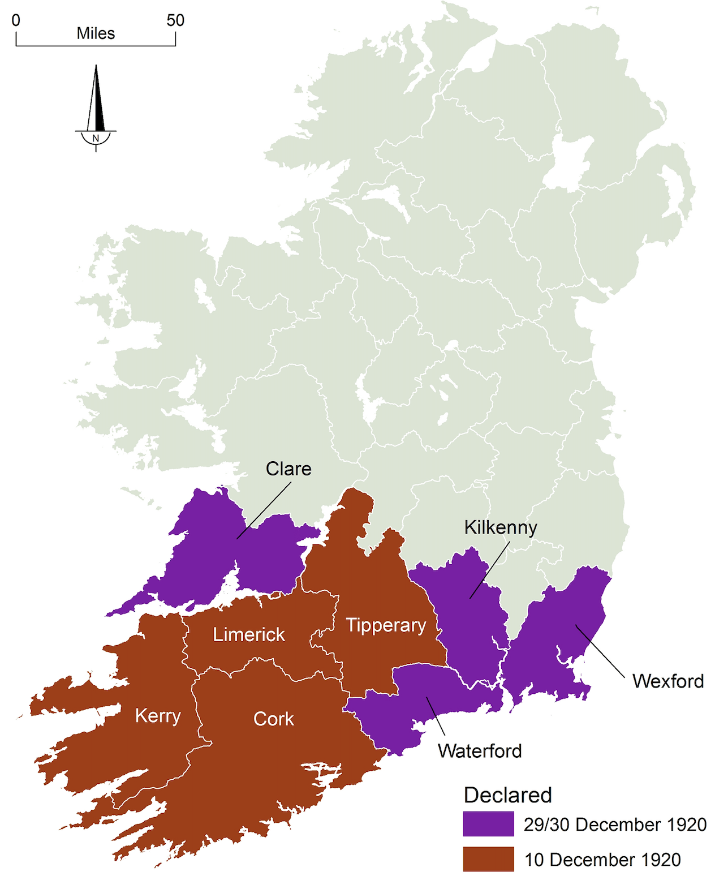

On 10 December the Lord-Lieutenant issued a proclamation from Dublin Castle placing counties Cork, Tipperary, Limerick and Kerry under martial law and appointing General Neville Macready, the commander of the British forces in Ireland, as Military Governor-General. Two days later, Macready approved a two-week weapons amnesty, after which anyone caught bearing arms or wearing the stolen uniforms of the Crown forces in the proclaimed areas would be executed. A separate proclamation sanctioned ‘official’ reprisals against civilians. On 29 December seven houses were destroyed in Middleton in response to an ambush earlier that day – the first of more than 150 properties destroyed in officially authorised reprisals in the first five months of 1921.

The application of marital law to only four counties was controversial. The military leadership argued the absurdity of Dublin being exempt and predicted that rebels could avoid the penalties for carrying arms by crossing into neighbouring counties. The Army had neither the manpower nor the resources to police the boundaries of the martial law area. As anticipated, the proclamation ordering the surrender of arms by 27 December had no effect and by the end of the month the Government had decided to extend martial law. Counties Clare, Kilkenny, Waterford and Wexford were proclaimed on 4th January 1921, and ‘a state of armed insurrection’ was declared to exist. Any person taking part in, or aiding and abetting this insurrection was ‘liable to suffer death after trial by a military court.’

The jurisdiction under martial law now largely corresponded with Major-General Sir Peter Strickland’s 6th Divisional Area. As Military Governor, he had wide-ranging powers to impose whatever regulations were deemed necessary for the restoration and maintenance of order. In the first of a series of proclamations, he made all crimes into offences punishable under martial law. From 4 January 1921, the owners of occupied buildings were required to ‘keep a list of inmates posted on the door’ and the proprietors of hotels and boarding houses were ordered to supply a register of guests to the police.

Subsequent proclamations prohibited loitering, sending telegrams in code and ‘the possession of wireless instruments or carrier pigeons’. Restrictions were also placed on holding fairs and markets, which, in the words of Lieutenant-General Percival, ‘provided opportunities for the IRA leaders to meet together and discuss plans’. On 28 April a public notice warned the people of Tipperary that ‘a civilian with his hands in his pockets is necessarily an object of suspicion … and renders him liable to arrest and, in an emergency, runs the risk of coming under fire.’ Failure to stop when challenged by a British Army curfew patrol on Castle Street in Cork city proved fatal for seventy-year old Denis O’Brien in early March. Such incidents went unreported in the local press which was heavily influenced by military censors in the proclaimed counties. They liberally applied the ‘blue pencil rule’ to newspaper proofs, suppressing content relating to everything from parliamentary statements to the names of persons arrested in the district.

A two-tier military court was created to try those contravening the provisions of martial law. Summary courts were established in battalion areas to deal with minor infractions where fines or short-term prison sentences were delt out. In mid-February, for example, the Freeman’s Journal reported that a young man from Abbeyleix was ‘find £2 for cycling after hours in the Marital Law area’. On 30 January, Madge Daly, sister of Ned Daly, one of the executed leaders of the 1916 Rising, was fined £10 for failure to display list of the names of the inhabitants of her house on Ennis Road in Limerick. At the same hearing, her sister Una was fined £40 for removing a military proclamation posted in the window of the family bakery on Sarsfield Street.

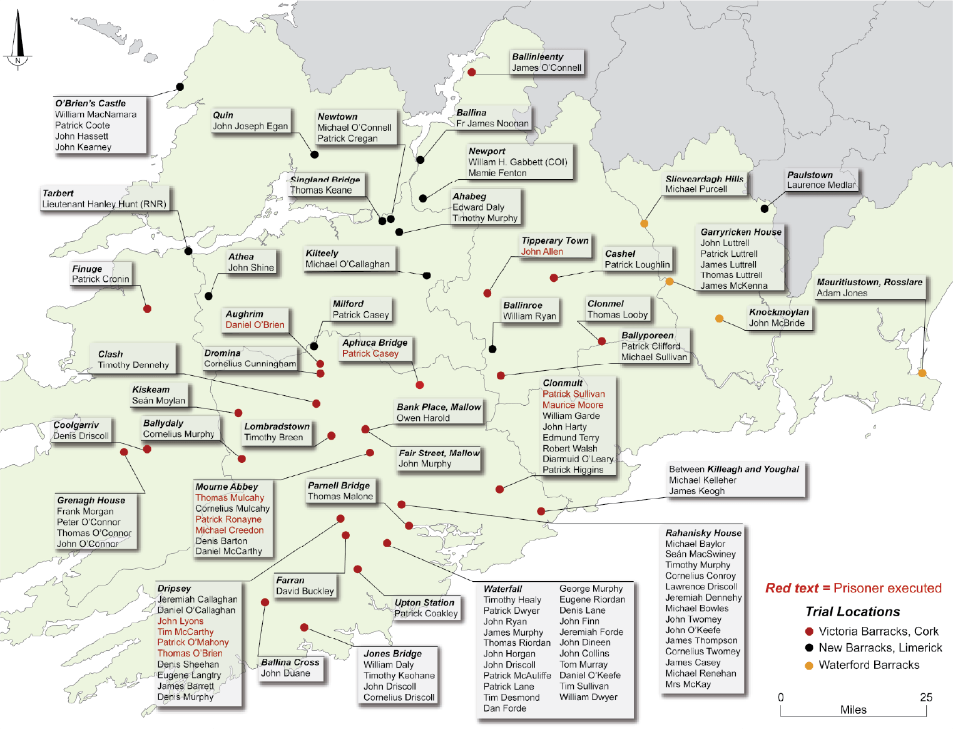

The upper tier of the military court was responsible for major offences against martial law such as the illegal possession of arms or taking part in an ambush. Military court trials were held at Victoria Barracks in Cork, New Barracks in Limerick and Waterford Barracks with thirty-seven capital convictions by the time of the Truce. The execution on 1 February of twenty-three-year-old Cornelius Murphy for being in possession of a loaded revolver was the first of fourteen between January and July 1921.

Caption: Military Courts 1921: The military instituted a range of counter-measures in the Martial Law Area (MLA), including the creation of a two-tier Military Court to try those contravening the provisions of Martial Law. The Summary Court dealt with less serious infractions, trying 2,296 people and imposing 549 sentences of imprisonment. The upper tier was responsible for major offenses against Martial Law. This map shows the places of arrest of those tried in the upper tier of the Military Court, with the names of those executed inserted in red. [Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution 2017)].

The decision to impose martial law raised the temperature of the conflict in Munster, and the first six months of 1921 were by far the most violent of the War of Independence. IRA officers in the proclaimed areas were ordered to ‘go on the run’, bolstering the flying columns and sparking new levels of activity in areas that had been fairly quiet before 1921. For its part, military command reinforced the southern 6th Division, deployed armoured vehicles and airplanes and stepped up intelligence gathering activities. As well as carrying out ‘official punishments’, British soldiers engaged in offensive operations such as large-scale ‘round-ups’ and internment without trial. Reprisals and executions were met with IRA counter-reprisals such as the assassination of twelve British soldiers in Cork city following the execution of four Volunteers on 28 February for their part in an attempted ambush in Dripsey. From early 1921, military patrols were increasingly held up by IRA road blocking operations. Trees were felled, trenches dug and bridges blown up, particularly in lonely rural areas which often became staging posts for ambushes. The military, in turn, fortified their vehicles and began to carry republican hostages to deter their would-be attackers. Between January and June 1921, the IRA and the Crown Forces engaged in a seemingly perpetual campaign of tit-for-tat retaliation, terror and counter-terror.

When martial law was first announced in December 1920, the Irish Independent speculated about the range of measures that might be applied, warning readers that ‘the potentialities placed in the hands of military authorities have practically no limitation.’ In practice, however, the military was disillusioned by what they considered a half-hearted measure. Key equipment such as lorries and armoured cars were in short supply and military intelligence efforts proved insufficient to identify and capture IRA leaders. Most significantly, martial law failed to deliver the promised unity of command. There was confusion about military authority over the police in the proclaimed counties and judgements dispensed at military courts could be appealed in civil court. Martial law also provided immense propaganda capital to Sinn Fein, who cast the British government as unlawfully occupying Ireland and overseeing brutal military reprisals against the civilian population.

By the summer of 1921 it was clear that neither side was going to win a clear victory. The changing nature of the conflict and the long list of casualties convinced the leaders on both sides to seeks a negotiated peace. The Truce came into effect on 11 July 1921.

– This article by Dr Helene O’Keeffe was first published in the Irish Examiner on 2 January 2021 –