- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

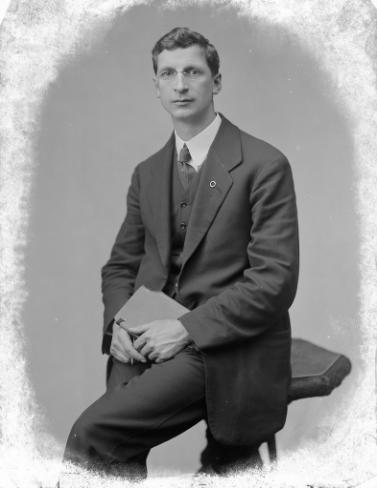

De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

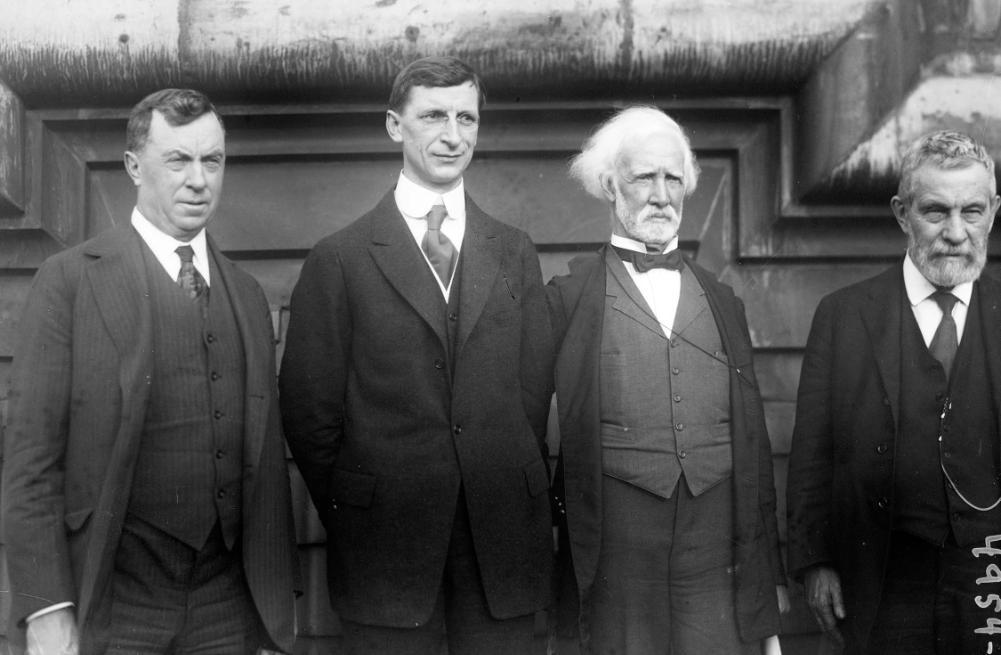

Éamon de Valera (1882-1975) with leading Irish-American figures at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel, New York, 23 June 1919

Dr Helene O’Keeffe explains the reasons for, and details of Eamon de Valera’s tour of America between June 1919 and November 1920.

Eamon de Valera’s eventful 1919 began in Lincoln Jail and ended in New York’s Waldorf Astoria, the largest and most luxurious hotel in the world. Smuggled aboard the SS Lapland in Liverpool in June, he sailed for the United States during the closing stages of the Paris Peace Conference. As London’s Sunday Express complained in August 1919, ‘there is more Irish blood in America than in Ireland’, making the United States the obvious destination for a sustained propaganda and fundraising mission.

Writing in 1998, a journalist for Florida Times-Union provided context for de Valera’s arrival in the US almost eighty years before:

“The nation was busting a gut after World War I. Flaming youth was charging blazes-bent into the Roaring ‘20s. The Feds were busting commies. The cops were chasing robbers. Bathtub gin was catching on. Women were bobbing their hair. Sin was having a field day. Into the roiling springtime came de Valera to America to free Ireland.”

After his highly-publicised American debut at New York’s Waldorf Astoria, the self-styled ‘President of the Irish Republic’ embarked on the first leg of what would be an eighteen month tour of the United States. The purpose of his mission was twofold: to gain formal recognition of the Irish Republic and to raise funds via a bond issue to support the independence movement and the newly established Dáil Éireann.

Between July and August 1919, de Valera and his entourage travelled over 6,000 miles from New York to San Francisco, addressing enormous crowds at dozens of venues. He filled Madison Square Garden to capacity and received a thirty-minute standing ovation from 25,000 people in Chicago’s Wrigley field. Twice as many people filled Boston’s Fenway Park on 29 June, cheering the arrival of the ‘Irish Lincoln’. The Sinn Féin envoys also visited less obvious Irish communities of the period, such as Scranton, Savannah, New Orleans and Kansas City. For de Valera’s personal secretary Sean Nunan, the public meeting in Butte, Montana was like ‘an election meeting at home – there were so many first-generation Irishmen working on the mines – mainly from around Allihies in West Cork’. In San Francisco de Valera dedicated a statue of Robert Emmet by Irish-born sculptor Jerome Connor in Golden Gate Park – a replica of which stands sentinel in St Stephen’s Green in Dublin. This was one of many symbolic gestures linking the American and Irish struggles for independence played out before the flashing bulbs of the ubiquitous press photographers. On 15 August the Cork Examiner noted that the enthusiastic American exchanges ‘indicate that few public missionaries from other lands – possibly only Mr Parnell – have ever had such receptions as were accorded to the Sinn Fein leader.’

De Valera’s team deserves credit for the incredible logistical triumph that was the US tour. As chief organiser, Liam Mellows travelled ahead to each city, ensuring a suitable reception was prepared and a venue secured for a mass meeting. Sean Nunan was de Valera’s fastidious personal secretary and Harry Boland, Sinn Fein TD for South Roscommon and IRB envoy, was at his side troubleshooting, speechmaking and shaking hands. As the tour progressed the Chief’s supporting cast expanded to include, Kerry-born Kathleen O’Connell who became de Valera’s full-time personal secretary from 1919.

Map showing the locations visited by Eamon de Valera during his tour of the United States in 1919 and 1920. [Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution (CUP, 2017)]

The next stage of de Valera’s American odyssey began on 1 October 1919 in Philadelphia, a city with a rich Irish heritage and rife with symbolism of America’s struggle for independence. Over the next three weeks, the Chief and his team travelled from the Atlantic to the Pacific seaboard and back again, delivering seventeen major public speeches and a host of smaller ones to aggregate crowds of over half a million. As Harry Boland noted in his diary: ‘If cheers and parades mean anything we have won. Wish we could translate cheers into deeds.’

The pace was relentless as the Irish team made its way through middle America. De Valera was received as a visiting dignitary at multiple state legislatures and presented with honorary degrees from six American universities. In line with his secondary objective to foster the interest of ‘wealthy men of the race in the industrial development of Ireland’, the Irish president addressed the Chambers of Commerce in a number of cities and arranged a personal meeting with Henry Ford, the son of an Irish emigrant, during his visit to Detroit in October. In the same month in Wisconsin, de Valera was made a Chief of the Chippewa Nation, an honour he later said meant more to him than all the freedoms of all the cites he was ever given. It is not surprising that by the time they reached Denver on 30 October, the Irish World reported that ‘the President looked tired. He has been speaking entirely too much and is certain to have a breakdown if there is not some let-up in his programme.’ He still mustered the energy to make high profile visits to Portland, Los Angeles and San Diego before beginning the return journey to New York the end of November. Sean Nunan recalled a brief hiatus at the Grand Canyon: ‘The President and I hired cow ponies and rode down the canyon – a most pleasant change from the official engagements of the past two months.

After a short break for Christmas, the Irish team prepared for the launch of the Bond Certificate Drive. A week-long frenzy of publicity kicked off on 17 January at New York’s City Hall where Mayor John F. Hylan presented de Valera with the Freedom of the City. In a hurried letter on 20 January, Sean Nunan reassured Michael Collins that ‘things in the loan department are going in good style. The Drive opened with a meeting at the Lexington Theatre, where $2,400,000 was pledged in behalf of New York City.’ During the Spring of 1920, de Valera addressed the Maryland Legislature at Annapolis before making the swing through the southern states of America. In the meantime, reports of increasing violence in Ireland were reaching America, not least the fatal shooting of Cork’s Lord Mayor Tomás MacCurtain. In March Michael Collins replied sardonically to Sean Nunan, who had complained of some organisational difficulty: ‘Oh yes. I am fully aware of all the little troubles you have had in the New World, but the little troubles here are so absorbing that one is inclined to forget them.’

It had not been all plain sailing for the Sinn Fein representatives in America. The tour of the west coast in late 1919 saw increasing tensions with American patriotic bodies who were critical of de Valera perceived pro-German stance during the war. He was heckled during a speech in Seattle and a tricolour was ripped from his car in Portland by members of the American Legion. The trip through the southern states in the Spring of 1920 coincided with rising American anti-immigration and anti-Catholic nativism. Even before de Valera’s arrival in Florida in April, the local chapter of the America First Association placed adverts in the Florida Times, proclaiming, ‘Ireland is not on the map of the United States.’ A small number of counter demonstrations were organised by right wing Americans. Most notably, members of the Ku Klux Klan made unwelcome appearances at several rallies in the American south, making clear their opposition to de Valera’s presence.

The Irish envoys also contended with antagonism from the leaders of Friends of Irish Freedom (FOIF) – the broad-based popular front of Clan na Gael headed by veteran Fenian John Devoy and Judge Daniel Cohalan. The FOIF used its significant resources to finance de Valera’s tour and facilitate the Bond Certificate Drive, but behind the scenes there were significant personality clashes and tensions over tactics. Seventy-seven-year-old John Devoy expressed his irritation in a letter to Harry Boland on 6 September 1919.

Every man who comes here from Ireland not alone misunderstands America but is filled with preconceived notions that are wholly without foundation, as well as belief that he knows America better than those who have spent most of their lives in the country or were born in it.

The increasingly public dispute came to a head in a row over strategies at the Republican National Convention in Chicago in June 1920. Drawing on his influential political contacts, Cohalan persuaded the Republican Party to include Irish self-determination in their election platform. However, much to Cohalan’s fury, de Valera led a separate delegation to the Convention and insisted on a resolution calling for recognition of the Irish Republic. In Sean Nunan’s words: ‘The result was that two resolutions were submitted to the Platform Committee, which indicated dissension in the Irish ranks and gave the Committee the excuse to include neither in the final platform’. After de Valera also failed to secure the endorsement of the Democratic convention in San Francisco in June, it was clear that the Irish question would not be a significant factor in the ensuing presidential election. Relations between the FOIF and de Valera reached a new low. In November of 1920, de Valera made the final break with the FOIF and set up a new organisation, the American Association for the Recognition of the Irish Republic.

De Valera was in Washington on 25 October when Terence MacSwiney died after 74 days on hunger strike. Six days later, at the last great meeting of the American tour, 40,000 people filled New York’s Polo Grounds to commemorate MacSwiney’s death. By late November, de Valera knew that it was time to return to Ireland. Smuggled aboard SS Celtic in New York harbour on 10 December, de Valera prepared for the nine-day journey home. He had failed to obtain the recognition of the United States Government for the Republic, but the rebel president’s cross-continental tour and associated press coverage raised international awareness and over $5 million for the Irish cause.

– This article by Helene O’Keeffe was first published in the Irish Examiner on 24 March 2020 –