In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Dr Donal Ó Drisceoil explains how the success of Sinn Féin in the local elections of 1920, and the subsequent declaration of allegiance to Dáil Eireann by the vast majority of local bodies in the country, was a significant milestone in the republican struggle.

The success of Sinn Féin in the local elections of 1920, and the declaration of allegiance to Dáil Eireann by the vast majority of local bodies in the country that followed, was a significant milestone in the republican struggle.

The elections were the first since 1914 and presented the republican movement with an opportunity to copper-fasten its democratic legitimacy following the famous general election victory of December 1918 that led to the establishment of the Dáil and the declaration of Irish independence.

In 1918 Sinn Féin won a disproportionate number of seats for its vote share under the prevailing ‘winner-takes-all’ or ‘first-past-the post’ system. In an effort to hobble the party, the British government introduced the Proportional Representation – Single Transferable Vote (PR-STV) system for the 1920 local elections in Ireland. This had been trialled in the one-off Sligo Corporation election of January 1919, when the combined nationalist/unionist Sligo Ratepayers’ Association won eight seats to Sinn Féin’s seven, indicating that PR might be a way of weakening the republican party.

The municipal or urban elections for the city corporations, urban district councils and town councils were held in January 1920, followed in June by the rural elections for county councils, rural district councils and boards of guardians.

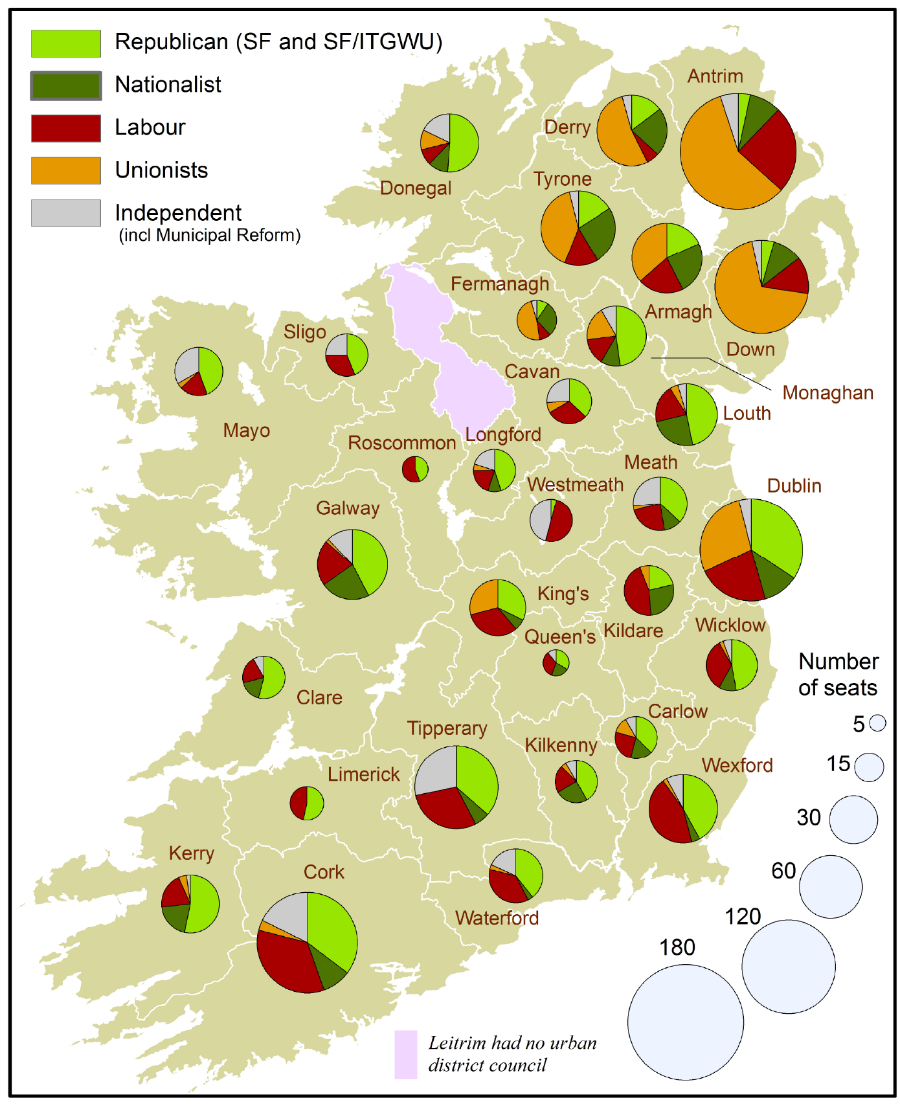

This map shows the share of seats won by parties by county in the urban elections (city corporations, urban district councils, town councils) of January 1920.

The PR system was new to the electorate and its intricacies had the potential to cause much confusion, but the Local Government Board made little effort to educate voters. Instead, this task was taken on by the Proportional Representation Society of Ireland (PRSI) and the political parties themselves, predominantly Sinn Féin. The PRSI distributed 125,000 leaflets and pamphlets around the country, ran advertisements in the press and displayed slides in cinemas explaining the system. A remarkably low spoiled-vote rate of under 3 per cent attested to their success.

The PRSI’s ‘An Elector’s Catechism’, published in the press, predicted a scenario that has become a standard feature of Irish elections ever since: ‘Under proportional representation a candidate is often able to secure victory at the very last moment. He may creep up on the fourth, fifth, or later counts and, although very low down on the poll after the early counts, he may find himself victorious before the close.’

The Sinn Féin programme emphasised local government reform, public health, and making local bodies the agents of the Dáil’s policy of commercial and industrial expansion. The Nationalist Party emphasised the danger of declaring allegiance to the outlawed Dáil and thus losing vital British government funding. Labour’s programme was a radical social-democratic one centred on housing, education and public works. However, both it and Sinn Féin had no illusions that the vote was primarily about making the local bodies levers in the independence struggle. In the words of the ITGWU paper The Watchword of Labour, ‘the incoming councils will be combatant rather than constructive bodies, fighting instruments rather than reform institutions.’

The turnout in the municipal elections was a very respectable 70 per cent. Sinn Féin emerged as the largest party overall, but less emphatically than in 1918, which seemed to partially vindicate the British strategy. It won 560 seats. The big surprise was the showing of the Labour Party, which had sat out the 1918 general election. It emerged as the second largest party, winning 394 seats. The Unionists came third with 368 seats, 302 of which were in Ulster. There was a surprisingly strong showing by the presumed-dead Nationalist Party (the former Home Rule/Irish Parliamentary Party), which secured 238 seats and outpolled Sinn Féin in first preferences in Ulster.

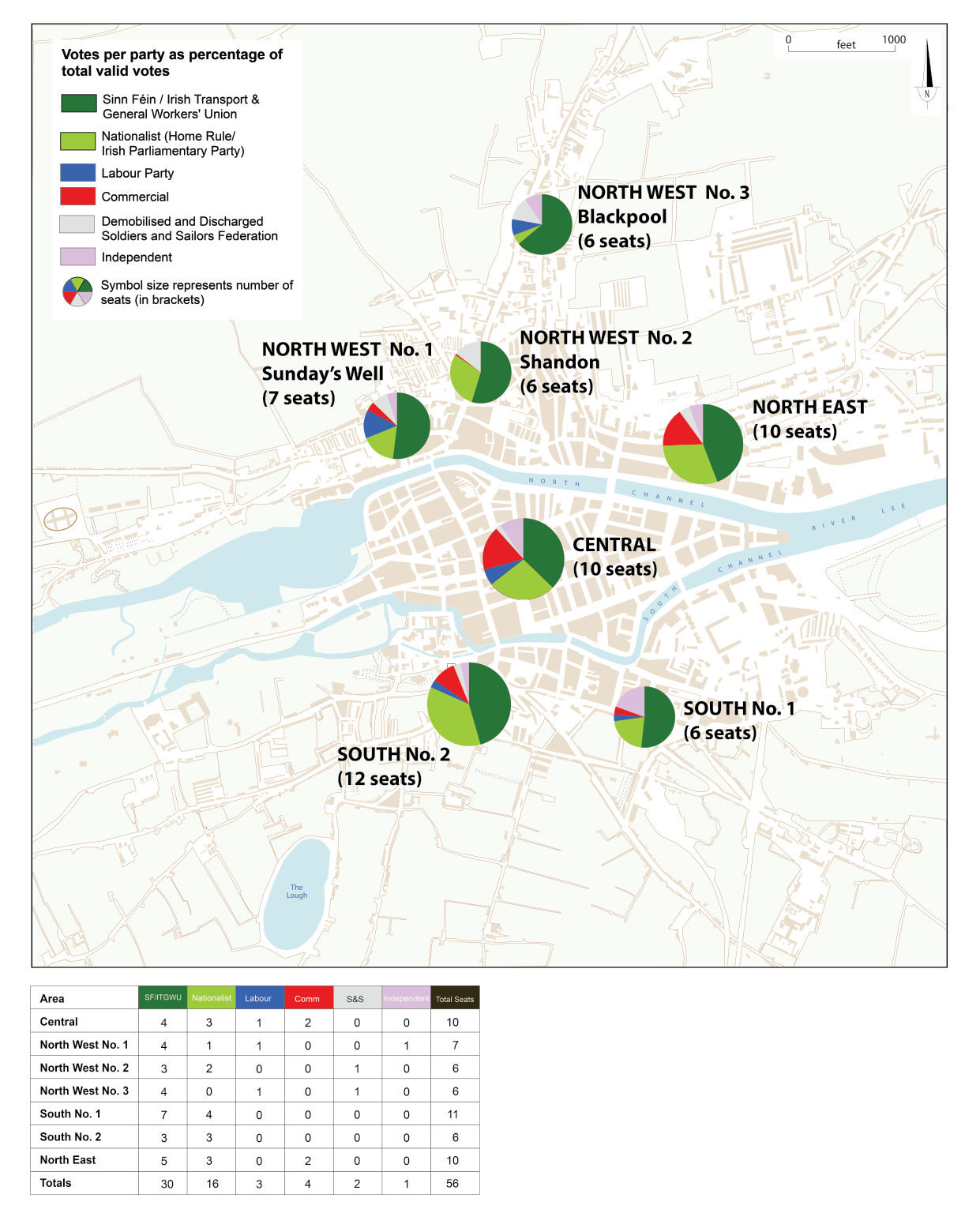

Sinn Féin and Labour, which was also pro-independence, had co-operated in many areas, and in Cork city the Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU) and Sinn Féin ran a joint ticket, putting up a full ticket of 56 candidates for the 56 vacancies across the seven city wards. The Labour Party candidates were nominated by the trades councils (local representative trade union bodies) across the country. In Cork, the ITGWU insisted that Labour should declare its allegiance to the Dáil, which it refused to do, resulting in the alliance with Sinn Féin. Labour had three councillors returned in Cork, but the SF/ITGWU ticket swept the board, winning almost half of all the votes cast and a majority of 30 of the 56 seats, including 11 of the poll-topping 14 aldermen. The Nationalists came second with 16 seats.

Sinn Féin secured 43 per cent of the votes in Dublin and won forty-two of the eighty corporation seats. With the exception of Belfast, Sinn Féin and its allies controlled local government in every Irish city and almost all of its towns. Derry was a special case, and the result there was hailed as one of the most significant of all.

Unionist gerrymandering traditionally ensured that, despite a 65 per cent Catholic/nationalist majority, unionists dominated the corporation. In 1920, sensing that PR might offer a historic opportunity, the Nationalist Party and Sinn Féin united on a single nationalist ticket with the support of Labour. The nationalists won a majority of two, leading to the historic election of the city’s first Catholic mayor since 1688.

The result was greeted by wild nationalist celebrations and, combined with numerous other unexpected nationalist and Labour victories across the six Ulster counties that would become Northern Ireland, was seen as a major rebuff to plans for partition. However, the Government of Ireland Act of December 1920 and the establishment of Northern Ireland, including Derry, in June 1921 put paid to the high hopes of January 1920.

PR was abolished for local elections in Northern Ireland in 1922 and in 1924 unionists recaptured control of Derry Corporation.

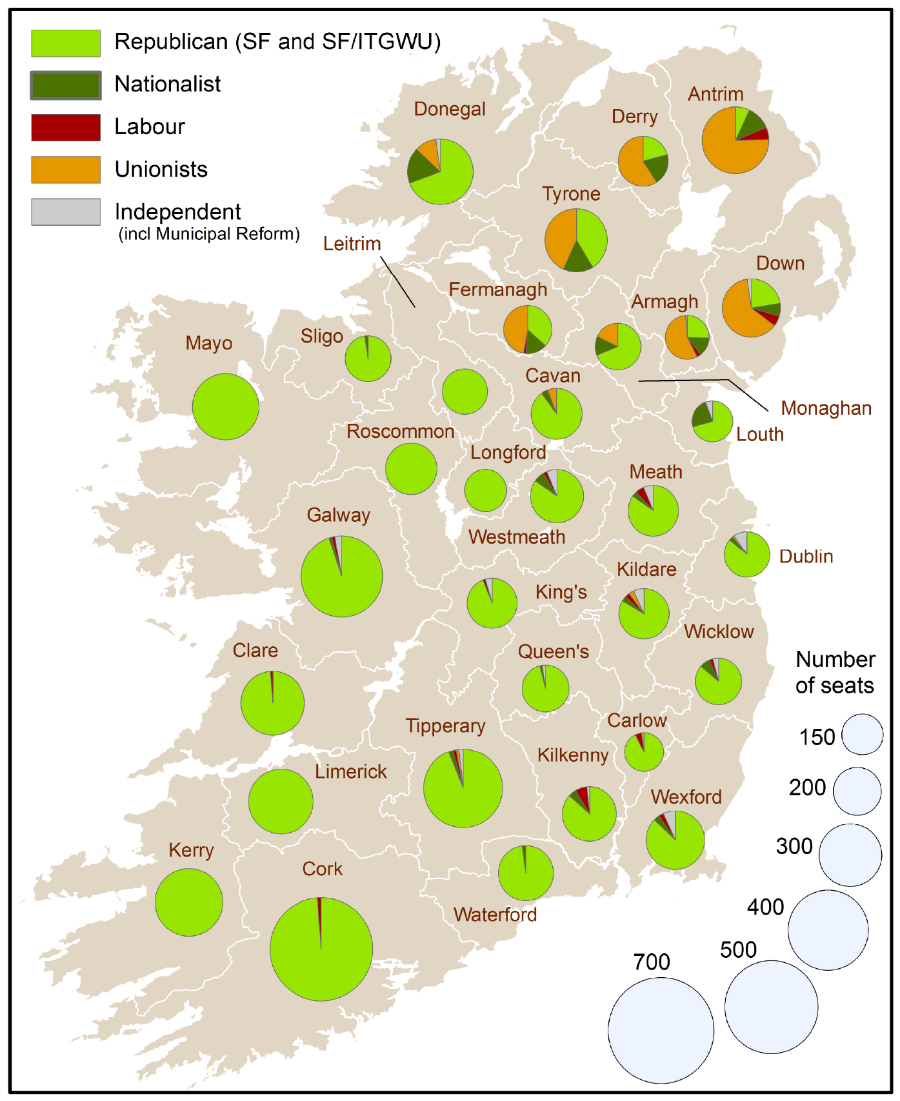

This map shows the share of seats won by parties by county in the rural local elections (county councils, rural district councils and boards of guardians) of June 1920.

The elections for rural bodies (county councils, rural district councils and boards of guardians) took place in June. These resulted in a far greater victory for Sinn Féin (running on a joint ticket with the Irish Transport & General Workers’ Union in several constituencies), which won just over 80 per cent of all seats countrywide, and 94 per cent in Munster. Outside of Ulster, many of the seats were uncontested. In Ulster, the party secured 41 per cent of the seats; the combined anti-partitionist/nationalist forces of Sinn Féin, the Nationalist Party and Labour secured a clear majority of 55 per cent of seats in the nine counties of Ulster.

Combining the results for the elections to all local government bodies, Sinn Féin (including Sinn Féin/ITGWU) won 69 per cent of the seats, Unionists 12 per cent, Labour and the Nationalist Party 7 per cent each and independents (including Municipal Reform) 5 per cent.

The vast majority of local government bodies outside of the four north-eastern counties declared allegiance to the Dáil following the elections, striking a significant symbolic blow to British authority in most of Ireland.

In and the tricolour was raised over the city hall. Less than two months later MacCurtain was dead, followed in October by his successor, Terence MacSwiney. By the year’s end, the Crown forces had burned the city hall to the ground and when the corporation met in the city’s courthouse in January 1921 to re-elect MacSwiney’s replacement, Donal Óg O’Callaghan as Lord Mayor, the meeting was raided by the police and military and nine of the republican councillors were arrested without charge and sent to internment camps. The euphoria of a year before seemed a distant memory.

This map shows the votes per party as a percentage of the total valid votes cast in the Cork city municipal elections in January 1920.

– This article by Donal Ó Drisceoil was first published in the Irish Examiner on 24 March 2020 –