In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Newspaper Reactions to the Easter Rising in Cork, Part 2

By Alan McCarthy, UCC School of History

During this period Irish newspaper enterprises played a key role in disseminating both the news and opinions, and occasionally intruded upon the narrative and become part of the news themselves.

In the years that preceded the Rising, the Cork City Press was characterised by the fractious nature of its newspapers, covering a broad political spectrum.

It is important to highlight the internal politics of Cork’s newspapers and their employees prior to the Rising, their reaction to the Rebellion itself and the transformative effect, if any, that this event had on their reportage. Dynamic personalities reflected, and indeed refracted, contemporary events for the popular newspapers of the day.

It should of course be noted that proprietors, editors, reporters, journalists and printers in Cork at this time would have been all men. These men belonged to the middle-class, and served as links between the high political figures of the time and ordinary citizens.

Before the Rising

Having briefly flirted with the concept of the All-for-Ireland League, the Southern Star resolutely recommitted itself to the Irish Parliamentary Party and its leader John Redmond in 1910. This move would invite yet another exchange of jibes and diatribes between the Eagle and Star which characterised and enlivened their co-existence.

Although the paper was often non-partisan, the All-for-Ireland League found a champion in the Eagle, whose primarily Protestant readership appreciated O’Brien’s policy of ‘Conference, Conciliation and Consent,’ which stipulated that any form of Home Rule government for Ireland would have to be acceptable to the island’s Protestant population.

What the Eagle’s readers did not appreciate were reports by the Star about All-for-Ireland League meetings, which made claims like “the hall was fairly well filled with a few pensioners and a few sightseers.”[i] The League’s official organ, the Cork Free Press, received much harsher abuse from the Examiner, whose editor George Crosbie stood for the Irish Parliamentary Party in 1909. [ii] The paper dubbed O’Brien a “factionist” and criticised the unionist Cork Constitution for giving the Mallow-native attention, as well as critiquing the pompous leading articles O’Brien occasionally wrote for the Free Press.[iii]

With its funds largely depleted, the Free Press was compelled to become a weekly paper in 1915, with Liam de Róiste commenting that

‘The Cork Free Press’ ceased publication as a daily yesterday. It went out with a weary sigh that the ‘old men’ could do no more: the fate of Ireland is now in the hands of the young men. True, Mr. O’Brien, quite true. And the young men are not doing badly: going to jail, shadowed by police, facing threats innumerable”

As far as the newspapers in Cork were concerned, however, the greatest threat being faced by the young men was the Great War in Europe, which dominated news coverage. While recruitment for the War received universal backing amongst Cork’s newspapers, the suggestion that Cork nationalists had quietly acquiesced to their position within the Union is undone by the violence with which O’Brienites and Redmondites clashed during this period.[iv] More advanced separatists like Pearse and De Róiste would find cause to lament, as nationalists had a host of literary, political, cultural and proto-military pursuits with which to stoke the fires of separatism.

The Rising and Reaction

Consequently, the idea that a group of radicals and socialists could undermine the efforts of the war in Europe appeared abhorrent. The Press in Cork mirrored the national press in greeting the Rising with general bewilderment and disbelief.[v]

Initially, the Examiner misjudged the Rising to be a “communistic disturbance, rather than a revolutionary movement,” with the daily paper obviously facing greater pressure for publication at a time when, by its own admission, the full facts were not known.

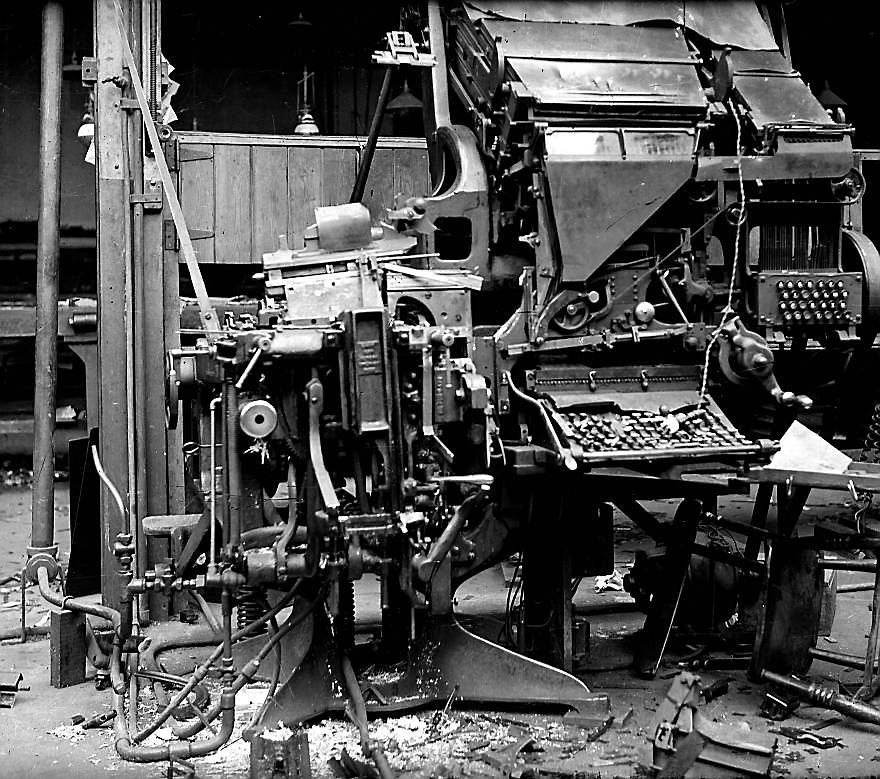

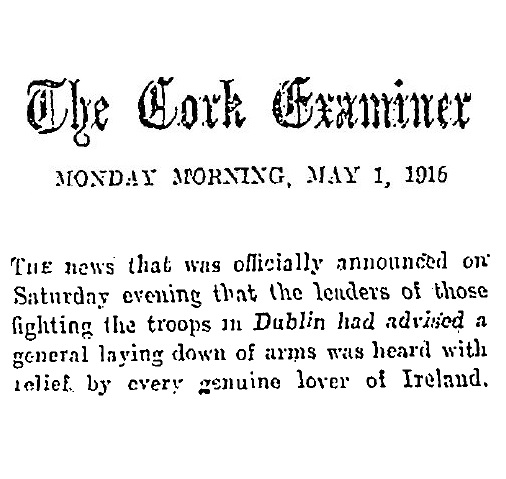

Among the participants was the paper’s own printer, Riobard Lankford, who was promptly dismissed from his post for taking part in the insurrection.[vi] The Examiner was relieved by the cessation of hostilities, a sentiment they believed would be expressed “by every genuine lover of Ireland. We trust that this means that the end is well in sight, and that little remains now but to count the cost in lives and hopes that are to be laid at the door of this mad enterprise.”[vii]

Other papers were even more closely connected to the action. The Tivy family-owned Cork Constitution and Weekly News had the most vitriolic reaction to the Rising of the Cork papers, dismissing the insurgents as “wreckers” and the Proclamation of the Irish Republic as “arrant nonsense.”[viii] A year prior, the Tivy family purchased the Dublin Daily Express and its sister paper, the Evening Mail. At Easter-time 1916 both papers were occupied by rebels, with the Express later putting in a compensation application for £3 for an overcoat taken by insurgents and used as a disguise when exiting the building.

Closer to home, the Cork Constitution was to have a major impact on the Cork Corps of the Irish Volunteers. While “Dublin [was] in a state of revolution,” as Tivy wrote to his wife Nellie on April 27th, the Cork Volunteers were confined to guarding their premises.[ix] This was largely attributable to poor organisation and communication stemming from I.R.B.’s Supreme Council., as meticulously detailed in the research of Gerry White and Brendan O’Shea. Having learned of an agreement between MacCurtain’s Volunteers and the authorities to hand over their weapons in exchange for a pardon, thereby living to fight another day, Tivy’s Constitution published a story about the negotiations, jeopardising them in the process. While the arms were handed in, General Maxwell did not honour the agreed-upon truce agreed and with mass round-ups ensued. The directness with which the Constitution assessed the rebels was mirrored by its handling of the Roger Casement trial. While the likes of the Southern Star sympathetically offered career sketches of Casement that highlighted his glowing record as a diplomat and humanitarian, the Constitution captioned its reports in his trial for high treason with headings like ‘Traitor Casement.’[x]

The Cork Free Press was less certain about what position to adopt. Frank Gallagher, the Free Press’s last editor, came into conflict with the newspaper’s owner, O’Brien, for wanting to convey moderate approval of the Insurrection.[xi] It is probable that Gallagher would have been supported in this alteration in tone by Patrick O’Driscoll, another member of the editorial staff.[xii] Former owner and editor of the Fenian weekly The West Cork People, O’Driscoll was also the brother-in-law of Michael Collins. O’Driscoll’s involvement with the Free Press has long gone overlooked, but may well provide further explanation for the Free Press’ support for the rebels. This support critiqued the fool-hardy nature of the endeavour, but heaped praise on their courage and conduct in multiple articles published in the months after the Rising. Significantly, the Free Press was one of the first papers in the country to adopt a primarily supportive position. O’Brien’s change of heart was no doubt encouraged by a raid on the Free Press’s premises in the aftermath of the Rising, along with William O’Brien’s opposition to the policy of execution and what he saw as the “barbarities” of Martial Law.

While the Southern Star thought the Rising was a “mad, insane, hopeless project,” the paper also challenged “cowardly fellows, who would run away from a mouse, casting aspersions on a man like Pearse.”[xiii] The Dublin executions, along with that of Thomas Kent in Cork encouraged appeals for leniency. On 13 May, the Star editorialised that “The plea for clemency has grown into an irresistible demand.”[xiv] A week later the paper’s Skibbereen and Carbery correspondent poignantly prophesised: “We wonder how many of the people up and down the country who have recently been crying out for vengeance against a certain body of men, will in twenty years have succeeded in persuading themselves and be trying to persuade others that they were always heart and soul with these men.”[xv] The Eagle struck a tone not too dissimilar, proffering some sympathetic pieces, but leaning primarily towards shock, stating that the Rising represented “a period of bloodshed, rapine and disorder which few cities in the world have ever experienced,” albeit acknowledging that their countrymen were “misguided.”[xvi] While the suggestion that the executions served to turn the tide of public opinion is well-trodden territory, it is important to note that many papers had taken up the approach of stressing the good conduct and character of the rebels, thereby exacerbating the sense of distaste and disquiet with which the executions were met.

Attention would soon shift back to the European War over the summer of 1916, particularly the conflict in the Somme, albeit with a hint of war weariness creeping in. Censorship and suppression would come to shape the climate in which the press operated in the wake of the Rising.

Sources

[i] Skibbereen Eagle, 9 April 1910, p. 2

[ii] Maume, Patrick, The Long Gestation: Irish Nationalist Life 1891-1918, Gill & Macmillan, Dublin, 1999, p. 100

[iii] Cork Examiner, 20 May 1910, p. 4, 21 June 1915, p. 4

[iv] O’Donovan, John, “Nationalist political conflict in Cork, 1910,” Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society, Vol. 117, 2012 p. 42

[v] Laffan, Michael, The Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Féin Party 1916-1923, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005, p. 47

[vi] U156/3, Period 1, p.1. Langford outlines how he officially lost his job owing to his “activity in the Volunteer movement.” Lankford Papers, CCCA. Edward Keegan, a clerk at the Irish Times, would be similarly dismissed for his participation in the 1916 Rising. See Jones, “Southern Unionism”, p.197 and O’Toole, Irish Times- Book of the Century, p.81

[vii] Cork Examiner, 1 May 1916, p. 4

[viii] Cork Weekly News, 6 May 1916, p. 1 and p. 6

[ix] U116/A/32, Tivy Family Papers, Note delivered to Nellie 27 April 1916, CCCA

[x] Southern Star, 20 May 1916, p. 2; Cork Weekly News, 6 May 1916, p. 4

[xi] O’Sullivan, David Richard, “William O’Brien, The Irish People and the Cork Free Press: voices of conciliation and conflict”, MA Thesis, UCC, October 2009, pp. 52-3, Maume, The Long Gestation, p. 181, Maume, Patrick, “A Nursery of Editors: The Cork Free Press, 1910-16,” History Ireland, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Mar. – Apr., 2007), p. 46

[xii] The Irish Times, 7 September 1940, p. 6

[xiii] Southern Star, 6 May 1916, p. 5

[xiv] Southern Star, 13 May 1916, p. 5

[xv] Southern Star, 20 May 1916, p. 5

[xvi] Skibbereen Eagle, 6 May 1916, p. 4