In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Dr Donal Ó Drisceoil explains how the Sinn Féin effectively won the battle for hearts and minds during the War of Independence and how the Propaganda war was just as significant as the military conflict

The battle for hearts and minds – in Ireland, Britain and beyond – was in many ways as significant, if not more so, to the Irish independence struggle as the military engagements that dominate the representation of the period. In a new age of mass democracy and mass media, the war of words and images was central to the struggle and its outcomes.

This could be called the propaganda war, and it was a war that Irish republicans won hands down.

In some ways, the |IRA campaign in 1919-21 was less about inflicting military defeat on Crown forces than drawing them out – forcing the British to show their hand – and then showing them up to the world. The war was as much about the use of moral force as of physical force – about asserting the rightfulness and justness of Ireland’s cause and the wrongfulness of British denial of Irish rights, and the immorality and injustice of British policies in Ireland.

Terence MacSwiney – whose hunger strike and death was such a major event in the swaying of international opinion on the Irish question – famously declared (though it is often misquoted) that ‘It is not those who can inflict most but those who can suffer most who will conquer.’

And in that vein, Robert Lynd, an editor with the British paper the Daily News, wrote very perceptively of the republicans in May 1919 that ‘They have a theory that whatever happens cannot but end in favour of Ireland. They seem to have a paradoxical belief that England cannot injure them without terribly injuring herself. They do not believe they could defeat the armed forces that might be sent against them but they believe that they could defeat the purpose of those who make use of the armed forces.’

This followed on the British and international refusal to accept the results of the 1918 election and the claims of Irish democracy. US global power was now being established and its continuing financial support for Britain gave it enormous influence. President Woodrow Wilson’s commitment to self-determination for small nations was a very selective one – it applied to the nations of the defeated Austro-Hungarian empire in central and eastern Europe, who would he hoped provide a bulwark against Bolshevik Russia, but not to the victims of colonialism in India, Africa, East Asia or the in the US sphere of influence in the Caribbean – and not to Ireland, the first colony of its ally Britain.

But Irish republicans made full use of his stated commitment to the ideal of self-determination for small nations in making the case for Irish independence. They placed the Irish struggle in a global context and sought to universalise the Irish cause. As Gavan Duffy, who was an envoy for the Irish republic in France and then Belgium put it, ‘Ireland stood for democratic principles, against imperialism and upon the side of liberty throughout the world’.

On the other side, British methods were presented as contrary to its claims to be a civilising force, some kind of champion of civilisation which had defeated the barbarous Germans. The suffering of Belgium at the hands of German militarism in the recent war was used to create parallels with Irish suffering at the hands of Britain.

The Irish Louvain’ – a view of the ruined remains of St Patrick’s Street following the ‘Burning of Cork’ on 11–12 December 1920. [Source: National Library of Ireland, HOGW 100]

In an era when the press and public opinion mattered more than ever before in politics and photojournalism was coming into its own, newspapers and journalists were anxious to use their power to focus on the morality of the methods used by a great power to suppress a popular movement that had widespread international sympathy. Ireland became a liberal cause célèbre, a focus of international attention where bigger conflicts than just the particular issue of Irish independence were being fought out. This was repeated in the coverage of the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s, and the closest analogy in the present day would probably be Palestine.

Ireland had hit the front pages of the world in 1916 and the British established a special Irish press censorship so that ‘news should not reach the neutral countries, and particularly our friends in America, which would be calculated to give them an entirely false impression as to the importance of what has taken place’.

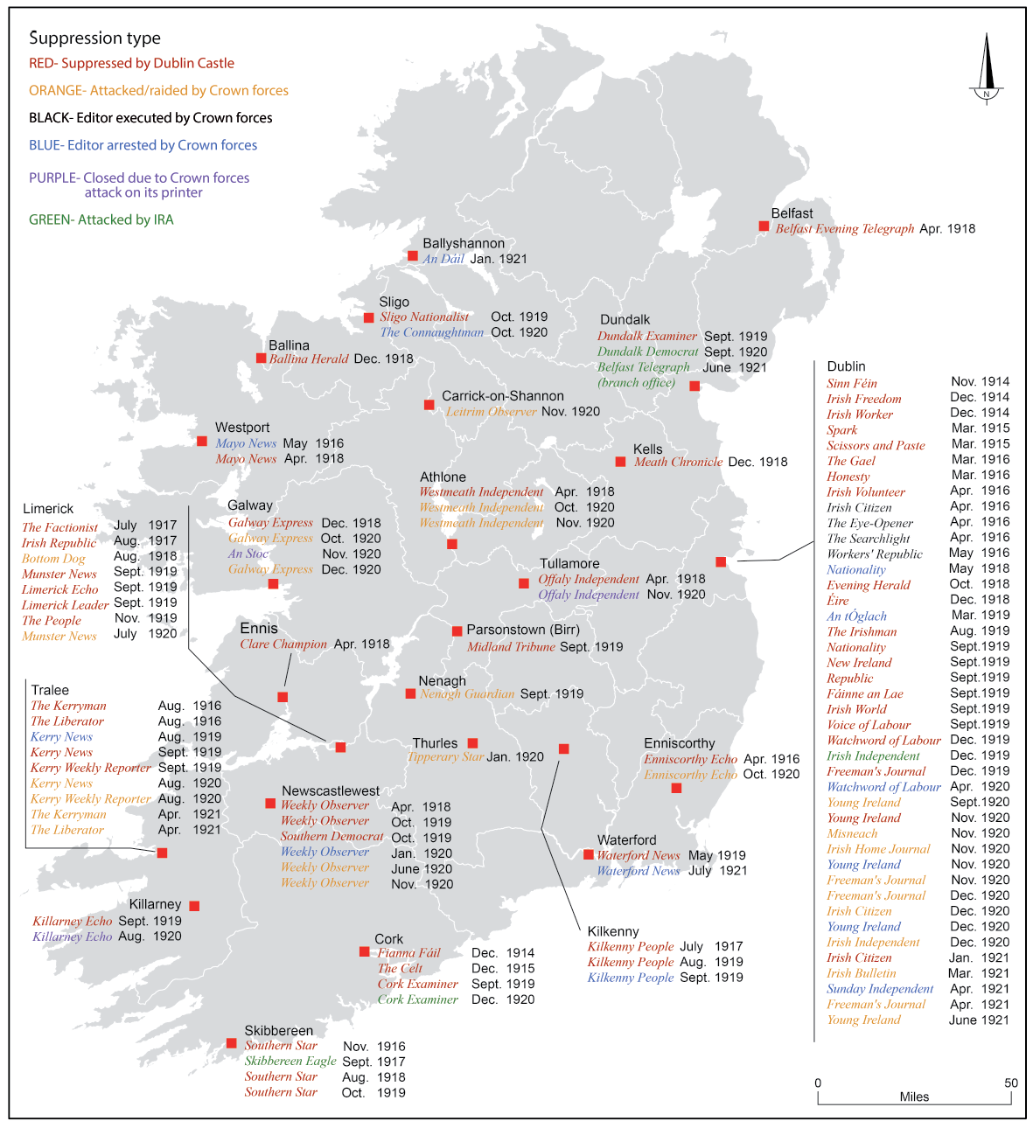

The Irish censorship system, 1916-19, was run by Lord Decies, who set out to manage the media in order to hobble the advance of republicanism. This was media management rather than repressive censorship, so, for example he would occasionally allow papers free rein to report radical speeches from the likes of de Valera in the hope of alarming or alienating moderate opinion. Papers that refused to toe his line had their presses dismantled, but this was rare. The 1918 victory of Sinn Féin and the establishment of the Dáil signalled the failure of this policy; the British then resorted to a more repressive approach to the press – what republicans dubbed ‘lawless censorship’. Thirty-six newspapers were put of circulation in 1919-21 period, forcing the Irish media to tone down its coverage of Crown force behaviour and stop carrying news supplied by the Dáil.

Suppression of/attacks on newspapers, December 1914 to June 1921 [Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution, (CUP, 2017)]

It was at influencing British and international opinion that the resources of republican publicity were primarily aimed; the battle for a majority of Irish minds was already largely won, aided by the alienating activities of the Crown forces on the ground.

The attempt to achieve recognition of the Irish Republic at the post-war peace conference at Versailles failed, not least because Woodrow Wilson opposed it. So the Dáil now set out to seek public support across the world for that position in order to pressurise their own governments and, in turn, the British.

The Dáil’s Department of Propaganda was directed by Desmond FitzGerald and Erskine Childers, and it was they who hosted visiting British, American and other journalists who were drawn to the exciting events in Ireland. Fitzgerald and Childers were British-born ‘men of letters’, already well-connected in British media and literary circles, and they cultivated close relationships with correspondents and ensured the ‘news from Ireland’ reflected the revolutionary agenda. The Dáil established press bureaux in Paris, Berlin, Rome, Madrid, Geneva and in the US, and spread its propaganda through support networks to an even wider global audience.

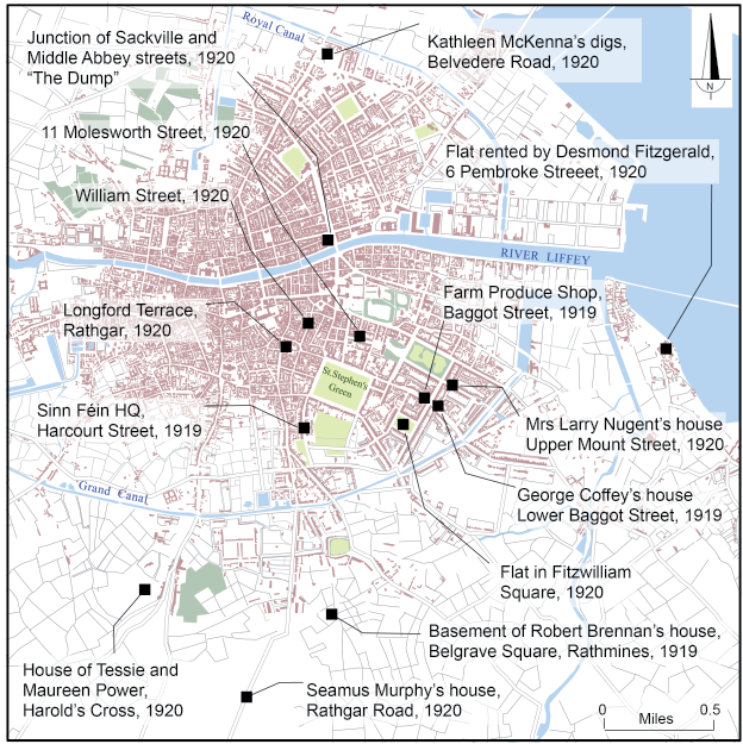

The Irish Bulletin, which chronicled the activities of Dáil Eireann and the military efforts of the British to suppress these, began in November 1919. Widely distributed, its contents were translated into several languages. The Bulletin carried an air of reliability and was trusted by the international media, as well as diplomats and politicians, far more that British propaganda. It emphasised British repression and atrocities, particularly the collective punishments meted out to the Irish people.

Map showing the locations in Dublin where the influential weekly Irish Bulletin was produced from its first issue in November 1919 until the Truce in July 1921. [Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution, (CUP, 2017)]

The British were much slower in realising the importance of the propaganda war and only established a special propaganda office – the Public Information Branch – in August 1920. This was regarded with suspicion by most journalists and newspapers and failed to counter the colouring that republicans had managed to put on coverage of events in Ireland. The Manchester Guardian considered government-supplied news ‘unscrupulous propaganda’, while other British dailies were likewise sceptical about such ‘doped’ or doctored ‘news’.

British black propaganda suggesting that Terence MacSwiney had been planning the assassination of the Catholic Bishop of Cork (!), or that he was secretly taking food during his hunger strike, made no impression. Rather, according to Desmond Fitzgerald, ‘The endurance and death of Alderman MacSwiney received extraordinary publicity and impressed the world with the heroic nature of Ireland’s struggle against England.’

Reporters flocked to Ireland from all over the world, including Britain, and one of the most important in terms of influencing British public and political opinion was Hugh Martin, who gathered his reports from Ireland into a book – Insurrection in Ireland (1921) – where he writes that ‘no honest man who has seen with his own eyes and heard with his own ears the fearful plight to which unhappy Ireland has been brought could fail to curse in his heart the political gamble that bred it or cease to use all the power of his pen to end it’.

And he did play a big part in ending it, despite being threatened and harassed by the Crown forces and denounced in Britain, along with his colleagues, as mouthpieces for Sinn Féin. He and others played a huge role is exposing British atrocities and British cabinet minutes and parliamentary debates reflect how seriously they were taken and the impact they had.

A major factor in this reportage was the attempts by liberal journalists in Britain to reclaim their reputation of independence and of speaking the truth the power having allowed themselves to be become mouthpieces for the British state during the First World War. They now expressed outrage at how Britain was betraying its claims to stand for justice and fair play; that it was acting as it had portrayed the Germans as acting in the Great War, when British propaganda presented the conflict as civilisation versus barbarism, morality versus militarism. A photograph of Patrick’s Street in the aftermath of the burning of Cork in December 1920 went around the world with the title ‘The Irish Louvain’, after the Belgian town destroyed by the Germans in 1914.

Integral to the American moral arguments for entering the First World War was the humanitarian dimension. Future president Herbert Hoover led the establishment of humanitarian relief for Belgians and such campaigns provided the model for the humanitarian initiative called the American Committee for Relief in Ireland, which was formed in December 1920 after the burning of Cork. The publicity efforts of this committee and its adjunct, the Irish White Cross, doubled as highly effective propaganda for the Irish cause. This ‘humanitarian propaganda’ put significant moral pressure on the British government in relation to its Irish policies.

The historian Michael Laffan makes the point that the British government in 1921 ‘changed its policy more in response to international hostility and to the shame and revulsion felt by British public opinion, than as a consequence of military weakness or defeat’.

As we proceed through the decade of centenaries, we should remind ourselves that the war was fought on many fronts, and that ultimately the military campaign was primarily a mechanism for provoking a British response that would shame it in the eyes of the world and especially its own population.

The IRA fought the British military to a stalemate in the military war, but the Republic’s propaganda machine was the undisputed victor in the other war. Ultimately, one might argue, moral force triumphed over physical force.

– This article by Donal Ó Drisceoil was first published in the special Irish Examiner Supplement commemorating the centenary of the death of Lord Mayor Tomas MacCurtain on 20 March 2020 –