In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

In the theatre of war of the turbulent years from 1919 to 1921, Cork was the main act, writes .

From 1919 to 1921 County Cork was the most violent county in Ireland. The republican insurgency against the British administration produced numerous episodes that galvanised political opinion in Ireland and Britain, and briefly earned Cork an international reputation for armed resistance against the British Empire. Statistical evidence supports the prominence awarded to ‘Rebel Cork’ during the War of Independence. County Cork possessed nine per cent of Ireland’s population in 1911 but was over-represented in various measurements of revolutionary intensity.

The Military Service Pensions Collection shows an overall national strength of 115,476 Irish Republican Army (IRA) Volunteers; the IRA brigades in Cork accounted for 17,976 of that total, or 16 per cent. The national estimated strengths of all IRA flying columns and active service units in 1921 totalled 1,379 IRA full-time fighters, of which 466 (34 per cent) served in County Cork.

The Cork brigades dominated the IRA’s 1st Southern Division, comprised of units from counties Cork, Kerry and Waterford and west Limerick. One of fifteen IRA divisions, the 1st Southern Division possessed 26 per cent of the IRA’s rifles, 25 per cent of its pistols, and 58 per cent of its machine guns. The Cork IRA was responsible for roughly eighty-six of 403 Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) dead (21 per cent), and forty-nine of 158 British military fatalities (31 per cent). The importance of Cork is further evident in the Crown forces dispositions.

Five of the nineteen RIC Auxiliary Division companies operated in County Cork (26 per cent); eighteen of the British army’s seventy-seven battalions or equivalent units (23 per cent) deployed in Ireland by July 1921 were based there.

ACTIVE SEPARATISM

Two factors contributed to Cork’s active separatism. Firstly, the city and county had been a Fenian stronghold in the nineteenth century, a legacy that left embers of republicanism around the county.

Prior to the First World War, Cork city developed a small but vibrant separatist community that included a Sinn Féin branch, an industrial development association, experimental theatre, a diverse Gaelic League, the women’s republican group Inghinidhe na hÉireann, a small Irish Republican Brotherhood organisation and a Gaelic Athletic Association organisation dominated by republicans. This nascent republican circle attracted and retained young men and women (primarily Catholic) from the ‘respectable’ working classes and lower middle classes, drawn to the separatist message.

Secondly, unlike the rest of nationalist Ireland, County Cork did not support John Redmond’s constitutional nationalism. In the December 1910 general election, William O’Brien’s All-for-Ireland League defeated Redmondite candidates in seven out of eight Cork constituencies, attracting moderate unionists, militant separatists, trade unionists, small farmers and farm labourers. All-for-Ireland League centres later became republican hotbeds, and the party’s membership defected to the independence movement virtually en masse following the Easter Rising. The active Fenian and O’Brienite strands of nationalism probably explain the over-representation of Cork men and women in the republican elite in Dublin and London. The county’s distinctive political traditions added another significant layer to the economic, geographical, political, social and cultural factors that came together across Ireland during the First World War.

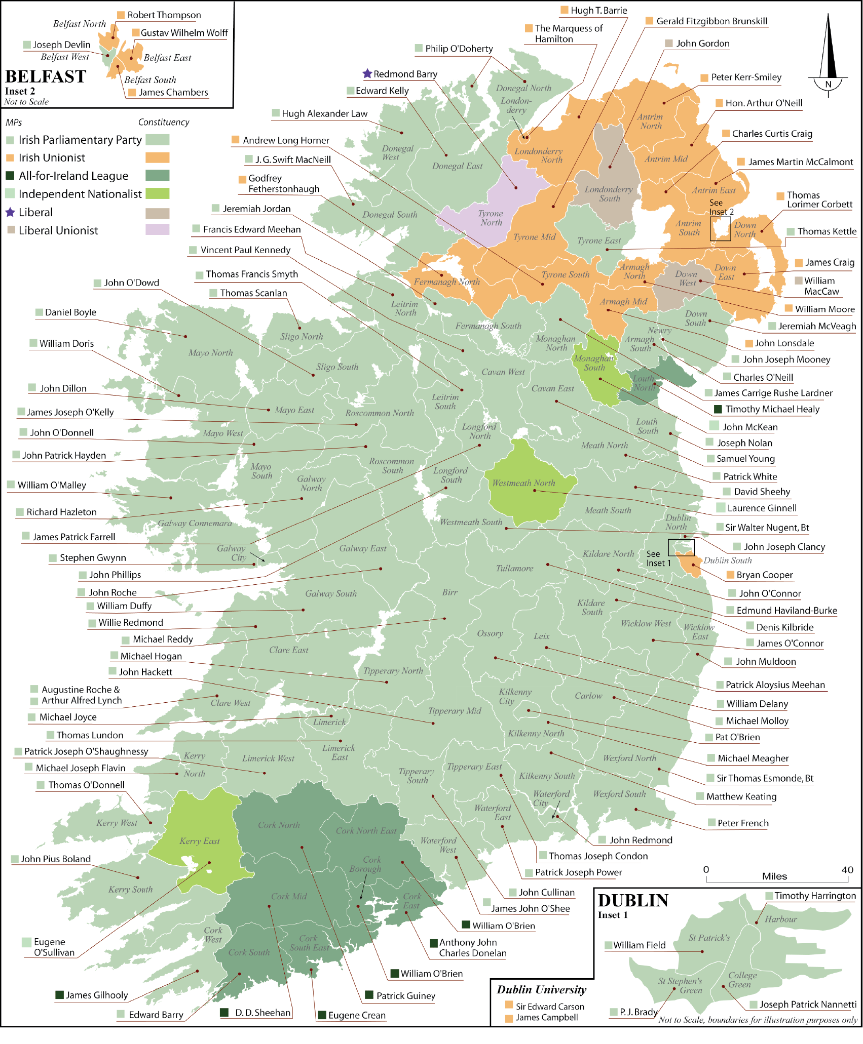

Caption: The results of the general election of January 1910, which saw John Redmond’s Irish Parliament party win seventy-one seats, put Home Rule at the heart of British politics. [Source: B. Walker (ed.), Parliamentary Election Results in Ireland, 1801–1922 (Dublin, 1978)] Map: Atlas of the Irish Revolution, CUP 2017

Cork separatists leapt at the opportunity presented by the foundation of the Irish Volunteers in late 1913. By the time of the Easter Rising, the County Cork Volunteers were among the best organised in the country, having secured some arms, set up branches throughout the county, and trained a cadre of potential leaders. They worked alongside the Cork branch of Cumann na mBan, which was a centre of strength for that organisation beyond Dublin. However, despite intensive preparations, Cork separatists sat out the 1916 Easter Rising. Confused by conflicting orders from their Dublin headquarters, the Cork Volunteers ultimately surrendered much of their weaponry without firing a shot.

Cork’s Easter Rising failure influenced the subsequent development of the Cork Volunteers. The organisation emerged from the Rising with structures, personnel and operational practices in place. This allowed the Volunteers movement in Cork to expand rapidly when public opinion moved towards republicanism in 1917. Easter Week failings generated a reappraisal of officers; those considered incompetent or insufficiently militant were nudged into the Sinn Féin organisation. Much of this transition occurred prior to the onset of hostilities with the Crown forces, allowing a robust organisation to emerge in the period of armed conflict.

The Cork Volunteers also seemed determined to compensate for their passivity during the Rising and consistently urged early armed action against Crown forces. Prior to the Soloheadbeg ambush, Cork Volunteers had attacked the Cork Men’s Prison, Eyeries RIC Barracks and a police patrol near Ballyvourney in 1918. More spectacular successes followed.

FLEXIBLE MILITARY ORGANISATION

Directed by Tomás MacCurtain and Terence MacSwiney, the Cork Volunteers built a flexible military organisation with a practical appreciation of the powerful British forces it faced.

In 1918 the Volunteers created a sophisticated communications system, with message-delivery stations established along primary and secondary roads selected to evade police observation. Intelligence gathering was also prioritised at an early stage. Internal discipline became strong, as individual Volunteers followed orders, kept appointments and accomplished their assigned tasks. Later success rested upon these solid organisational foundations.

The Volunteers in Cork remained organised in a single county-wide brigade until January 1919, when three new brigades were formed. Cork No. 1 Brigade took in Cork city and mid-Cork from Youghal to the county boundaries with Kerry; battalions were established in Cork city, Blarney/Donoughmore, Ballincollig/ Ovens, Cobh/Midleton, Whitechurch/Carrignavar, Macroom, Ballyvourney, Youghal and Passage West/Crosshaven. Cork No. 2 Brigade encompassed north and north-east Cork, with battalions created in Millstreet, Newmarket, Kanturk, Mallow, Charleville, Castletownroche and Fermoy. Cork No. 3 Brigade took in west Cork, starting from Kinsale, with battalions organised in Bandon, Clonakilty, Dunmanway, Skibbereen, Bantry and Castletownbere. Other units formed as the organisation expanded in 1920–21.

Though the Cork brigades operated independently of each other until 1921, their senior officers enjoyed collegial working relationships stemming from earlier collaboration. Each of the three Cork brigades developed separately but similarly, as officers built up confidence, aggression and expertise in guerrilla warfare. They each relied on thorough organisation and strong discipline, which ranked them among the very top IRA units in Ireland.

In early January 1920 the Cork No. 1 Brigade received sanction from IRA General Headquarters (GHQ) to simultaneously attack three RIC barracks, which perhaps offers a more logical starting point for the Irish War of Independence than Soloheadbeg. From this point until the autumn of 1920, Cork IRA units undertook a series of well-planned sorties that yielded precious arms and cleared strategic locales of their police presence. These early successes generated republican self-belief, inspired similar attacks in neighbouring areas, and damaged the prestige of the Crown forces.

On a practical level, newly seized weapons (especially rifles) enabled the IRA to tackle more ambitious targets. These early actions occurred prior to the hardening of Crown forces defences, giving the Cork Volunteers a head start over other brigades, which they never relinquished. They also instilled an independence of thought and action well suited to a rapidly evolving situation. The Cork Volunteers became ambivalent about the authority of IRA GHQ as they grew accustomed to arming, funding and thinking for themselves.

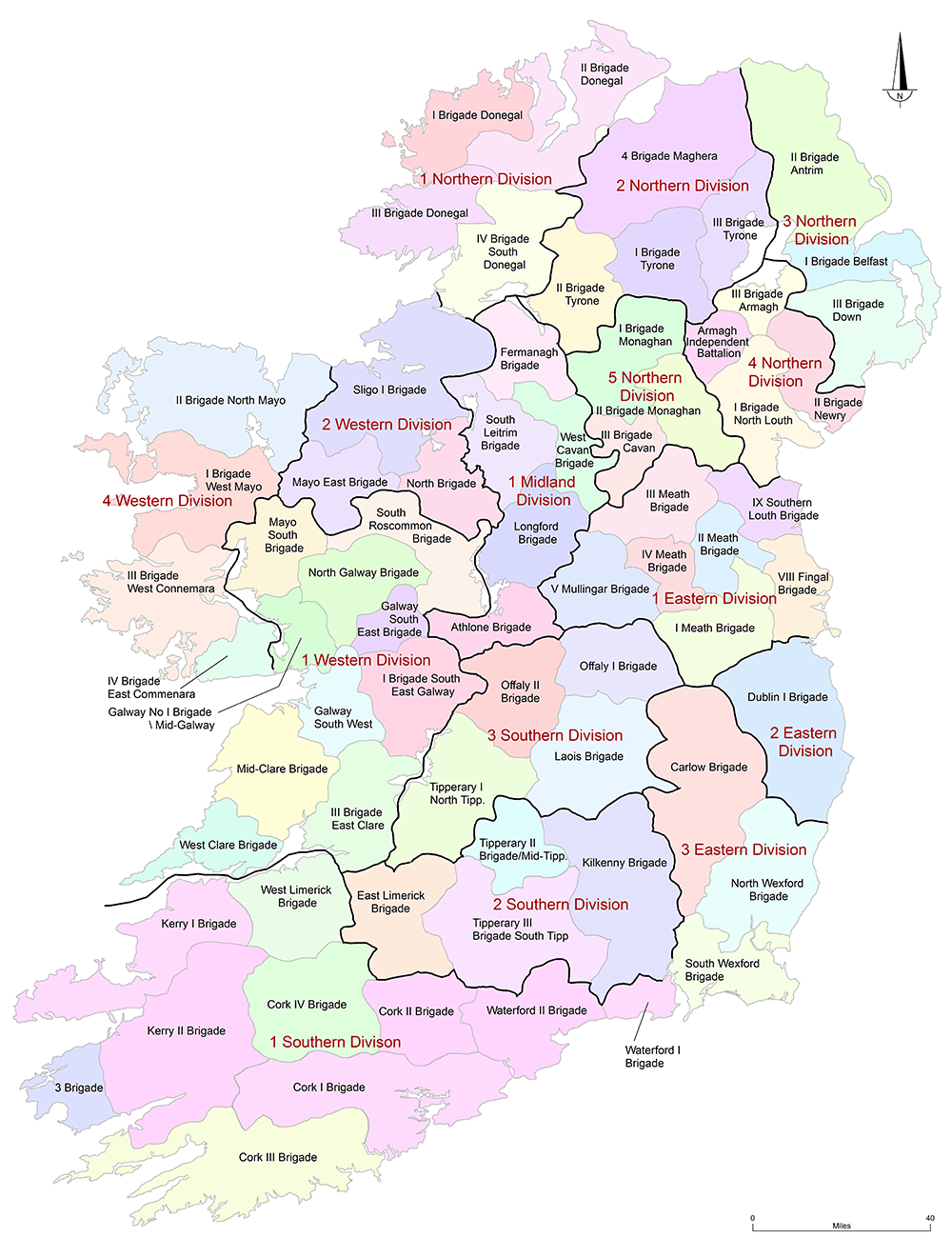

Caption: IRA Structure in 1921: Despite a lack of weapons and other material sources, the IRA built a sophisticated guerrilla army based on a parish-by-parish organisation. A town, rural area or urban neighbourhood/community formed a company; a number of companies comprised a battalion (usually a district, parliamentary constituency or barony); a number of battalions formed a brigade (typically a large part of a county). Late in the War of Independence and during the Truce period, brigades were organised into divisions. [Source: Irish Military Archives, Military Service Pensions Collection, IRA Nominal Rolls, RO/1-611] Map: Atlas of the Irish Revolution, CUP 2017

The audaciousness of the Cork brigades was striking. In 1920 and 1921 Cork Volunteers riddled Major General Strickland’s automobile with bullets; shot dead Brigadier General Cumming during a convoy ambush; kidnapped Brigadier General Lucas while he fished; assassinated RIC Divisional Commissioner Smyth (in command of the south Munster RIC) as he sipped brandy in the Cork County Club; and killed his successor Divisional Commissioner Holmes in another roadside ambush. Different IRA units captured the first RIC barracks (Carrigtwohill) and the last (Rosscarbery) of the conflict; seized for the only time a British army barracks (Mallow); and scuttled one Royal Navy warship (in Cork Harbour) and briefly captured another (a patrol craft at Castletownbere).

Cork Volunteers successfully attacked coastguard stations, lighthouses, airplanes, trains and armoured vehicles. Assassination squads were dispatched to Lisburn (County Down), England (twice) and New York City.

CAPABLE LEADERS

All the Cork brigades enjoyed intelligent and imaginative leadership. There were charismatic figures, like Seán O’Hegarty, Tom Barry and Seán Moylan; innovators, like Liam Lynch and Florrie O’Donoghue; tireless organisers, like George Power, Charlie Hurley and Liam Deasy; and daring and ruthless operational specialists, like Dan ‘Sandow’ O’Donovan, Paddy O’Brien and Seán Lehane. Despite suffering serious losses through death and capture, the Cork brigades quickly replenished their leadership ranks.

Their strength in depth stemmed partially from the early start to fighting in Cork, which required some officers to become full-time activists, a professionalisation process that improved their performance. But the organisation itself seemed to push the most capable men forward, a trait inherited from the original egalitarian and results-driven organisation begun in 1914. Intense conflict with the Crown forces also demanded steady and reliable administration; ineffectiveness, carelessness and lack of imagination could not be tolerated.

Militarily, Tom Barry’s west Cork flying-column victories have generated high interest (and academic controversy), not solely because of the popularity of Barry’s readable, if self-aggrandising, memoir, Guerrilla Days in Ireland. From late 1920 to 1921 Barry and his large flying column ranged across the Bandon Valley region, threatening British garrisons and drawing attention from the British cabinet. Yet Barry’s concentration of forces was risky, as defeat would have crippled the Cork No. 3 Brigade.

A better model was developed in the Cork No. 2 Brigade by Liam Lynch, whose units won a series of victories during the same period. In late 1920 Lynch formed columns in each of his seven battalions, usually with a strength of about fifteen fighters. The small battalion columns worked together as needed and assembled and dispersed quickly. The Cork No. 1 Brigade likewise operated a number of battalion-sized columns, though the great distance within the brigade area only allowed collaboration from Macroom to the Kerry border. There, in the Shehy Mountains, the brigade created a safe haven that eventually hosted various headquarters and columns, well-protected by twenty-four-hour sentry posts at strategic viewpoints.

As the conflict escalated in late 1920, the Cork IRA adapted quickly. In early 1921 units paralysed the county’s road infrastructure, destroying bridges, felling trees and cutting trenches on virtually every highway and byway. This prevented the British from conducting quick raids and confined vehicles to a few road arteries, which could be kept under observation and attacked when opportune.

Republican bomb-making also improved, with different brigades producing landmines, bombs and hand grenades. As the British military upped the intensity, the Cork IRA responded by moving underground, literally, with hidden dugouts constructed in every company area in the county. The IRA in Cork funded its extensive operations by taxing the civilian population, with payments based on pre-war local-authority rate levels.

ORDINARY VOLUNTEERS

The iconic Cork flying columns were only the most visible part of a much wider movement, like the tip of an iceberg. They were supported by thousands of ordinary Volunteers, who scouted, cut roads, carried messages, gathered information and kept watch.

Unlike most of the IRA, the Cork battalions and brigades created numerous specialist departments for such tasks as scouting, signalling, record-keeping, engineering and transport. Supplies were secured (usually surreptitiously) and equipment stockpiled in hidden caches. Much of this activity was invisible to the Crown forces, who instead focused on fighters and leaders comprising what historians have called the ‘revolutionary elite’.

County Cork experienced a disproportionate share of Crown-forces reprisals. Military curfews were often enacted or made more severe to punish communities for IRA activity. The British military noted that in ‘official’ reprisals (property destruction authorised by senior British army commanders), ‘most of the punishment’ was carried out in Cork. Overall, ten of twenty IRA fighters executed by the British in the War of Independence were Cork Volunteers, shot at Victoria (now Collins) Barracks in Cork city. Republicans responded to British reprisals by documenting them through the collection of witness depositions. This testimony became the basis for republican propaganda, which echoed themes used by the British government to denounce German crimes in Belgium during the First World War. In December 1920 this technique brought world attention to the biggest reprisal of the period, when Auxiliary cadets set fire to part of Cork city centre after an IRA ambush, damaging or destroying over eighty commercial premises, as well as City Hall and the Carnegie Library.

In the spring of 1921 the Cork IRA responded to British arson attacks on the homes of republican sympathisers by burning down the residences of prominent loyalists, frequently those who were Protestant, wealthy and connected to the British administration. These ‘counter-reprisals’ seemed to convince Dublin Castle to cancel the policy of official reprisals, which had failed to curtail IRA operations but had increased antagonism from the civilian population. Civilians suspected of providing information to the Crown forces were much more likely to face IRA assassination in County Cork than elsewhere in the country. This propensity likely stemmed from the intense British counter-insurgency waged in Cork, the upgrading of the IRA’s information-gathering efforts, and the overall high levels of violence in the county.

The Cork No. 1 Brigade in Cork city was especially prolific in civilian executions, as it maintained a wide network of surveillance over city residents. While it has been suggested that the Cork IRA targeted civilian suspects on a sectarian basis, available evidence does not support this contention. However, the Protestant population in parts of west Cork feared republican intentions. Sectarian and political tensions in that locale later featured in the controversial ‘Bandon Valley killings’ of thirteen Cork Protestants in April 1922. Civil administration.

While republicans invested heavily in the military campaign, some success was also achieved in civil administration. During 1920 public bodies around the county swore allegiance to Dáil Éireann and made symbolic gestures, like flying tricolours from public buildings. In the face of government suppression, County Cork was one of the only parts of Ireland where Dáil Courts continued to function in 1921.

During the Cork Men’s Prison hunger strike in the autumn of 1920, republicans successfully mobilised Cork civil society to demand the prisoners’ release, organising demonstrations, prayer vigils and other shows of solidarity. joint Civic and Labour Council, comprised of elected republican officials and Cork trade unionists, co-operated closely with the IRA during such emergencies as the Cork hunger strike. Yet efforts at civil governance simply could not cope with strong suppression from the Crown forces.

The dangers of travel and oppressive military curfews made it increasingly difficult for public bodies to find quorums for meetings. In many parts of the county, local government barely functioned. The danger to republican office-holders was made clear by the assassination of Cork’s lord mayor, Tomás MacCurtain (also the commander of the IRA’s Cork No. 1 Brigade), by disguised police constables, which garnered considerable sympathy from the Irish public and the international press. The danger to the public created by the deteriorating security situation caused the Catholic bishop of Cork, Daniel Cohalan, to excommunicate IRA fighters in December 1920.

REPUBLICAN WOMEN

In this volatile environment, women played an increasingly important role. Republican women in County Cork had long worked alongside republican men in the Gaelic League, Inghinidhe na hÉireann and Sinn Féin. Cumann na mBan in County Cork developed perhaps the strongest organisation beyond Dublin.

Nationally, Cumann na mBan created district councils comprised of a number of branches in a region. In theory each district council was supposed to align to the IRA battalion in the same area. In reality uneven Cumann na mBan organisation across Ireland meant that only 32 per cent of IRA battalions were matched with a Cumann na mBan district council. However, in County Cork 75 per cent of IRA battalions enjoyed this relationship, which suggests that republican women, like republican men, were highly mobilised in the county. Cumann na mBan provided logistical support to Cork’s numerous IRA columns and headquarters staff.

IRA intelligence officers in Cork recruited numerous female operatives, while at least four women served as IRA staff officers at either the battalion or brigade level, more than anywhere else in Ireland. As the environment became militarised in County Cork, republicans deployed their humanitarian organisation, the Irish White Cross. Mainly administered by women, the White Cross supplied critical financial assistance to the families of republican prisoners and to the victims of government reprisals.

Overall, the escalation of the war in Cork created a demand for reliable activists regardless of their gender. Relatively large numbers of teenage Fianna Éireann boy scouts and the Clan na nGaedheal girl guides were likewise channelled into the republican war effort.

ORGANISED LABOUR

Cork republicans depended on organised labour, especially the more radical Irish Transport and General Workers’ Union (ITGWU). The refusal of Cork Harbour dock workers to offload British military equipment during the summer of 1920 critically escalated the national ‘munitions strike’ of dockers and railway workers. The Cork ITGWU and the Cork Trades Council led one-day general strikes against conscription (April 1918) and for the release of the Mountjoy hunger strikers (April 1920), and stoppages protesting the deaths of Lord Mayor Tomás MacCurtain (March 1920) and Lord Mayor Terence MacSwiney (October 1920).

In the 1920 local elections, a joint Sinn Féin and ITGWU ticket won a majority of the Cork Corporation seats; at times of city crisis, the ITGWU and the Cork Trades Council often collaborated with republicans, such as after the burning of Cork. Organised labour remained a key republican ally across County Cork throughout 1921.

Desperate to regain control of the civilian population, the British government declared martial law in County Cork and neighbouring Munster counties on 10 December 1920. Amongst other powers, the military was authorised to carry out ‘official’ reprisals against civilians and execute republicans captured carrying arms. By early 1921 the British army in County Cork had improved its intelligence capabilities; troop reinforcements strengthened the military’s hold on major population centres; and the deployment of airplanes and armoured vehicles added new dimensions to British operations.

IRA flying columns suffered heavy casualties at Dripsey, Mourneabbey and, especially, Clonmult. Having adjusted to IRA tactics, the Crown forces became more difficult to target, while republicans increasingly went on the defensive in the long summer evenings.

Crown-forces casualties stabilised during the last three months of the War of Independence in Cork, though armed IRA activity continued to grow. However, while British army leaders claimed to be on the verge of total victory at the time of the 1921 Truce, this belief was not shared by republicans. Writing from his mountain hideout near Gougane Barra shortly before the Truce, the senior IRA officer Florrie O’Donoghue assured his wife, ‘we shall have a warm summer, most probably followed by a cool winter … to put it in plain and inelegant language – the enemy is in the very devil of a knot’.

The 1973 book Kiskeam Versus the Empire celebrated armed rebellion in one north-west Cork village during the War of Independence. Other Cork communities became closely identified with the independence movement, such as Coolea, Newcestown, Mourneabbey, Knockraha, Donoughmore and Kilbrittain. However, most areas of County Cork did not achieve the same high level of republican activity as those locales, while in places like Skibbereen, Youghal, Kinsale and Crosshaven, clear public ambivalence to republican violence was apparent.

In 1920 and 1921 Corkonians across the political spectrum endured intense republican resistance to government authority and a harsh counter-insurgency campaign waged by the British state. Their experience embedded the conflict firmly in their collective memory, routinely sparking debates, discussions and enduring curiosity, both inside and beyond the county boundaries.

Crowds gather at a police cordon on St Patrick’s Street, Cork, c. Dec 1920. [Source: The Irish Examiner]

AGRESSIVE AND LETHAL GUERRILLA WAR IN CO. KERRY

Perhaps nowhere in Ireland was the Civil War fought as bitterly as in Co Kerry. While the Kerry IRA had been reasonably active and well organised during the War of Independence, it waged a yet more aggressive and lethal guerrilla war in 1922–23. Kerry republicans sustained determined armed resistance, inflicted heavy casualties on the National Army, and retained control of large swathes of the county for much of the conflict.

Frustrated by their inability to crush the republicans, National Army officers took extreme measures against the IRA. The Free State forces in Kerry included the ‘Dublin Guard’, comprised of IRA veterans. Many of its officers were closely associated with Michael Collins, including intelligence officer David Neligan and Major-General Paddy O’Daly, the commander of Free State forces in Kerry. Republicans accused both men of killing and brutalising republican prisoners. The toxic environment culminated in several unofficial reprisal executions by the National Army in March 1923, including the notorious ‘Ballyseedy Massacre’.