In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

An article by UCC’s John Borgonovo looking at the escalation of violence in the summer of 1920 and the most critical period in the War of Independence which occurred during the month of November 1920, when dramatic IRA attacks and Crown force reprisals drew international attention to events in Ireland.

In the first half of 1920, a republican military and political offensive greatly weakened both the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) and the British judicial system in Ireland. Resignations from the RIC soared, hundreds of police barracks were abandoned, and courts became empty. In growing desperation, the British government sought a military solution to its Irish problem. The RIC was overhauled, militarized, and placed under the control of an ex-soldier, Sir Hugh Tudor, who had no police experience or knowledge of Ireland. Tudor approved the recruitment into the RIC of ex-soldiers from England, Scotland, and Wales. These working-class temporary constables were quickly dubbed ‘Black and Tans’ by the Irish public. A more elite police fighting force, the Auxiliary Division of the RIC, was raised from demobilised military officers. Members soon became associated with ill-discipline and reprisals against civilians. In Dublin, the British Army organised a covert unit to take over intelligence duties in the capitol. They were part of a broader reinforcement of the British Army garrison in Ireland, which eventually exceeded 50,000 troops.

During the autumn of 1920, hunger strikes in Cork and Brixton prisons had garnered worldwide interest and raised tensions across Ireland. The death and burial of Lord Mayor Terence MacSwiney at the end of October provided a brief interlude before the ensuing storm of November.

The month started with the execution of the UCD medical student Kevin Barry, following his capture during a fatal IRA ambush of British soldiers in Dublin. Despite considerable public protest over his youth and mistreatment while in custody, Barry was hanged in Mountjoy Jail on 1 November. The same day, in Tralee, County Kerry, the RIC began a series of frightening reprisals against the civilian population, following the disappearance (and killing) of two of their police comrades. For nine days, police forced businesses to shut, enforced a strict curfew, and prevented food supplies from entering the town. They also burned the county hall and other structures, and fired into civilians as they departed Sunday mass. International press correspondents provided chilling eye-witness testimony, which drew attention to the emerging government policy of collective punishment against the civilian population for IRA transgressions. Yet British Prime Minister David Lloyd George believed the government’s hard-line policy was turning the tide, as he boasted to a London audience on 9 November that he had ‘murder by the throat’ in Ireland.

BLOODY SUNDAY

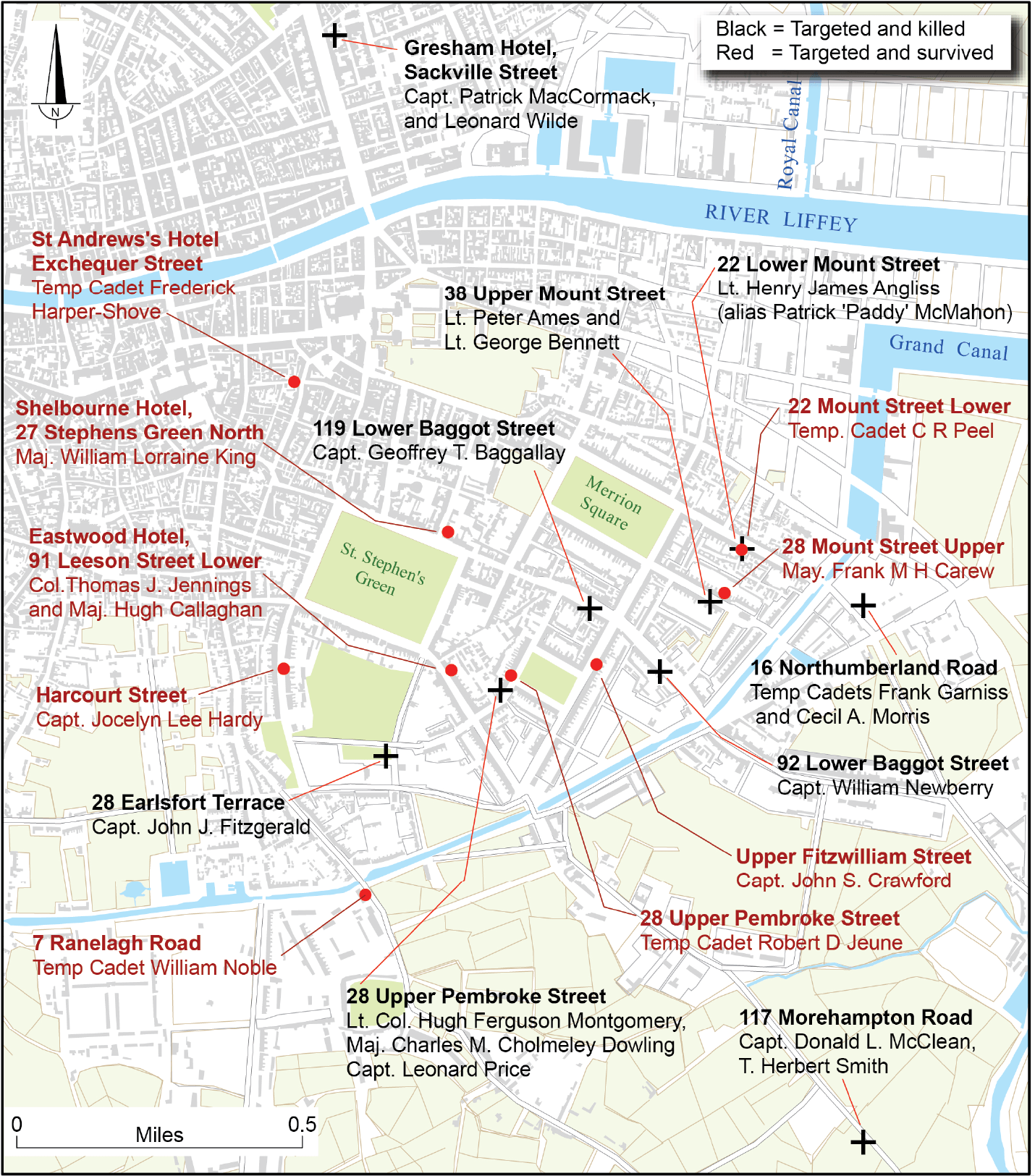

Less than two weeks later, events in Dublin shocked observers in Ireland and beyond. Since the summer of 1920, specially-recruited British Army officers had been working in a secret intelligence unit in Dublin. Dressed in plain clothes and residing without adequate security precautions in boarding houses, they were quickly detected by Michael Collins’ IRA intelligence department (managed by Liam Tobin). On the morning of 21 November 1920, Dublin IRA shooting teams simultaneously struck 14 separate premises housing 22 suspected British agents. The scale of the audacious operation was unprecedented, as scores of IRA gunmen shot dead 15 men (12 of whom were pre-targeted), many while still in their beds in fashionable areas of South Dublin. The operation’s effect on British intelligence has perhaps been exaggerated – only eight of the fatalities were in fact military intelligence agents (others were military legal officers and one or two were innocent). However, the psychological impact was enormous. No longer could British agents carelessly live among the civilian population beyond the protection of their military bases. The IRA had demonstrated to the entire British administration that it was vulnerable to IRA assassination at any time.

IRA attacks on ‘Bloody Sunday’, 21 November 1920. Most shootings occurred in a fashionable part of south Dublin, which was especially popular with Dublin Castle personnel. [Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution (2017)]

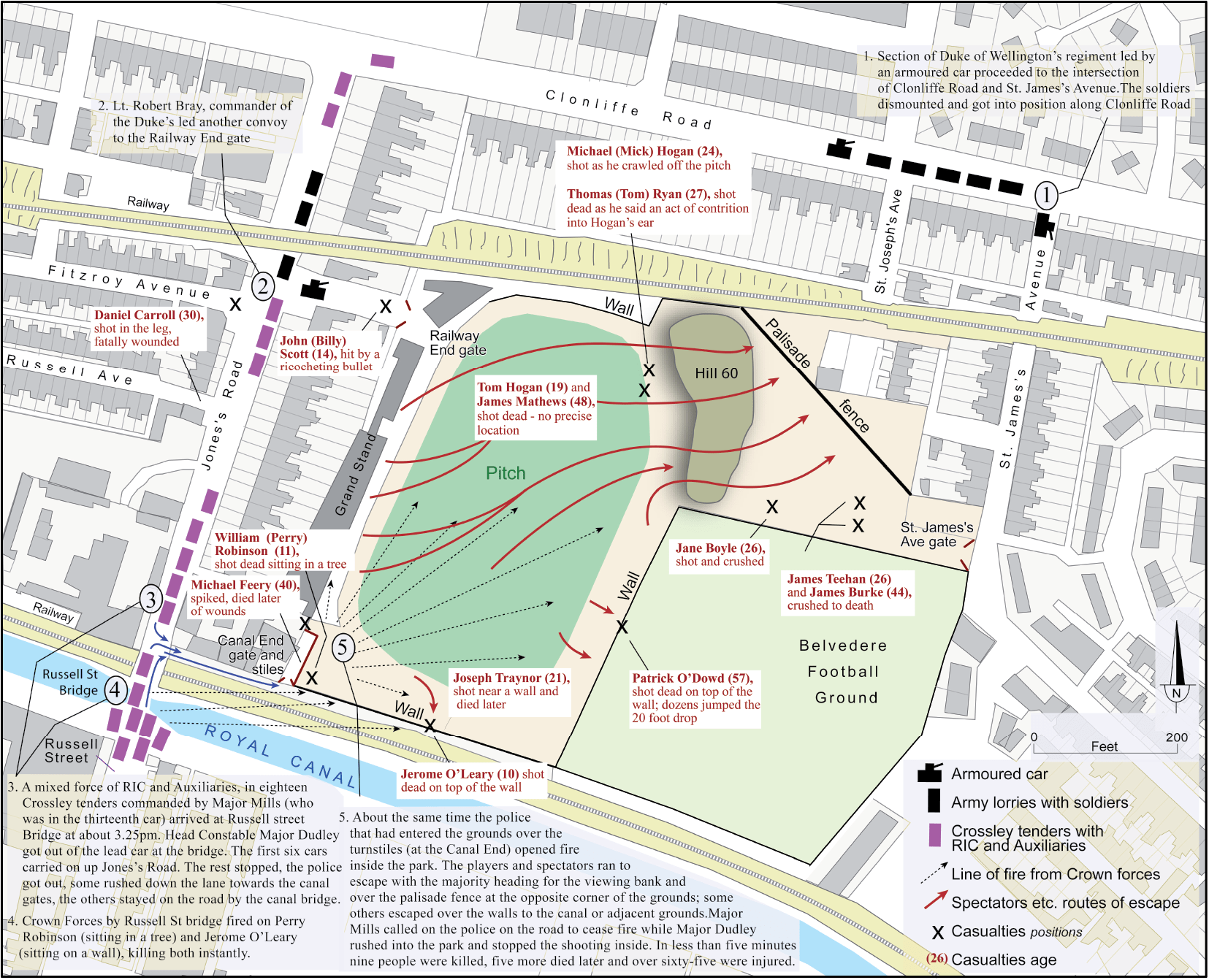

The British response to the IRA shootings was immediate and shocking. Within rattled Dublin Castle, it was believed that some of the IRA gunmen may have used attendance at the GAA football match between Dublin and Tipperary as a cover to enter the city. A large, mixed force of British soldiers and members of the RIC Auxiliary Division was dispatched to Croke Park to encircle the grounds and search male spectators for weapons. The operation may not have been pre-planned as a reprisal, but it was criminally reckless as its bloody outcome was entirely predictable. When the first police entered Croke Park, some constables opened fire on the crowd without provocation. Their shooting caused spectators and players to stampede, and other members of the Crown forces to fire indiscriminately into the fleeing throng. A total of 14 civilians were killed (11 shot dead and 3 crushed in the rush), and another 64 wounded or injured. Later that night, two senior IRA leaders, Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, were killed inside Dublin Castle while in police custody, probably after ill-treatment. A third man, Conor Clune, was killed with them, even though he was not a member of the IRA. His uncle, Patrick Clune, Catholic archbishop of Perth, Australia subsequently emerged as critic of British policy in Ireland and as a peace conduit between British and Irish governments.

Map showing the events at Croke Park on Bloody Sunday, 21 November 1920, when Crown Forces opened fire on the crowd during a challenge football match between Dublin and Tipperary, resulting in the death of fourteen civilians and the injuring of a further sixty-four. The incident followed the assassination earlier that day of twelve suspected British intelligence agents by Michael Collins’s ‘Squad’, and was followed by the killing later that evening of two leading Dublin IRA officers, Peadar Clancy and Dick McKee, as well as a civilian Conor Clune. [Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution (2017)]

British government officials and conservative newspapers expressed horror at the IRA killing of British Army officers while they were helpless in their bedrooms on a Sunday morning. The shootings were depicted as treacherous and beyond the rules of war, and the fallen officers given elaborate funeral processions in London. Government attempts to sidestep the Auxiliary Division’s stark brutality at Croke Park was less successful, leading at one point to nationalist Belfast MP Joe Devlin trading punches with Conservative MPs inside the House of Commons. Though the Irish Chief Secretary Sir Hamar Greenwood denied government culpability, eye-witness testimony collected by a British Labour Party investigation into the Croke Park killings, made it clear the shooting had been unprovoked. Croke Park fit into an emerging narrative of deliberate British state violence deployed against Irish civilians by out-of-control police units. That perception was gaining traction in the global press and causing dissent within Britain.

THE KILMICHAEL AMBUSH

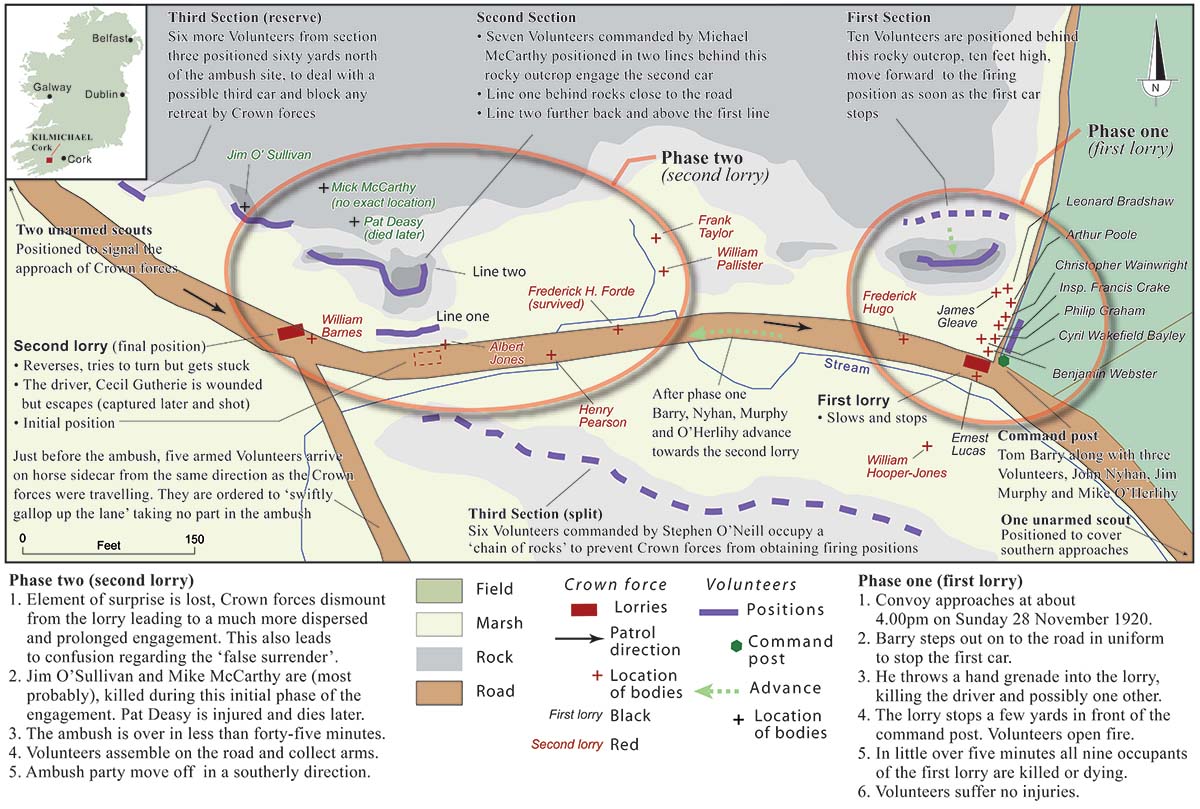

The RIC Auxiliary Division featured in the month’s final compelling episode a week after ‘Bloody Sunday’. On 28 November, a two-vehicle Auxiliary police convoy left Macroom Castle, county Cork and drove in the direction of Dunmanway. At dusk near Kilmichael, they were ambushed by an IRA party led by Tom Barry, a veteran of the First World War. The sharp fight left 16 of 18 ‘Auxies’ dead; one survivor was left for dead, while the other fled but was later discovered by another IRA unit and executed. Three IRA Volunteers also died in the encounter. British officials claimed the IRA had disguised themselves as British troops, overcame the Auxiliaries, then committed a ‘brutal massacre’ which included mutilating the corpses of the dead. According to one British Army official history, ‘as far as the cold-blooded brutality shown by the Murder Gang and the number of casualties to the Crown forces are concerned, it is quite the worst on record throughout the whole rebellion in Ireland’.

The Republican narrative of the affair reported that some of the police had committed a ‘false surrender’ near the close of the ambush; when IRA Volunteers emerged to disarm them, some resumed firing and hit at least two Volunteers. The iconoclast ambush commander Tom Barry subsequently claimed a ‘false surrender’ spurred his order to take no prisoners. Similar accounts of this version had been circulating in British and Irish circles since 1921. The false surrender narrative was generally accepted until the publication of historian Peter Hart’s 1997 book, The IRA and Its Enemies: Violence and Community in Cork, 1916-1923. Citing IRA veteran evidence, Hart reported that at least two of the police were killed after they surrendered, but Hart also proposed that a number of other constables may have died this way as well. Describing the ambush as a ‘massacre’, Hart suggested Barry never intended to take prisoners, thus questioning the entire ‘false surrender’ narrative. Hart’s interpretation of Kilmichael was challenged by a number of historians, who emphasized questions about the sources of Hart’s cited veteran testimony. Other historians and public commentators defended Hart’s methods and his findings. This charged dispute has rumbled on for over twenty years, continuing long after Peter Hart’s premature death in 2010, with new contributions anticipated in the future.

Beyond sparking an intense debate among historians, Kilmichael made an impression on British political and military leaders at the highest level of government. The event was referenced in the British Cabinet on multiple occasions, and subsequently offered as a partial explanation for another criminal act by the Crown forces, the ‘Burning of Cork’ on 11-12 December 1920. By then, Prime Minister David Lloyd George was no longer boasting that he had ‘murder by the throat’ in Ireland. The cascading events in November 1920 had shown government realists that the Irish insurgency would not be crushed so easily. Indeed, December and the first half of 1921 would offer even more unwelcome surprises for Lloyd George and his imperial supporters.

Map detailing events during the Kilmichael ambush. Source: Atlas of the Irish Revolution, (CUP, 2017)]

– This article by John Borgonovo was first published in the Irish Examiner on 2 January 2021 –