Introduction

By Dr Andy Bielenberg, UCC, and Professor Emeritus James S. Donnelly, Jr, UW-Madison

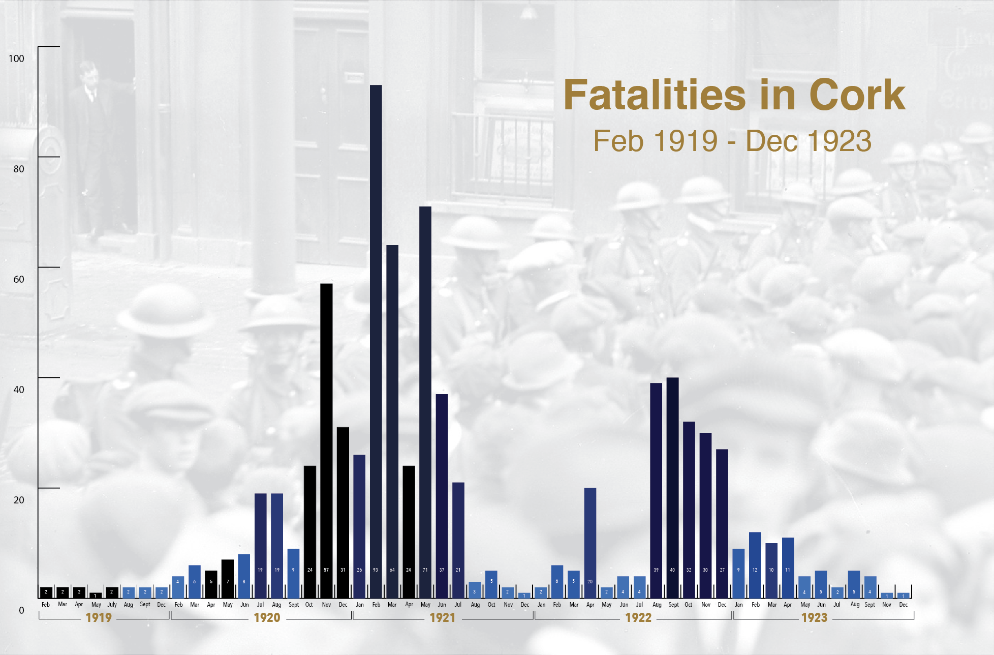

One of the outcomes of the Irish Revolution in County Cork was a high fatality level relative to other counties. This project has set out to record fatalities throughout the county between 1919 and 1923. This updated version now also includes the Truce and the Civil War; as such, it is now the most comprehensive record of conflict fatalities for County Cork during these years, identifying 827 deaths in total. In temporal terms fatality levels were highly uneven, with 538 taking place in the War of Independence, 53 during the Truce, and a further 236 in the Civil War. These figures starkly reveal the greater intensity of violence during the War of Independence in the county than later.

A monthly breakdown of the deaths recorded in this project across these years discloses that all the major peaks took place between the autumn of 1920 and the Truce on 11 July 1921 (see table above). The graph reveals the exceedingly limited level of fatalities in the early part of the War of Independence, which can justifiably be described as a ‘phony war’. Much of the Truce period and the latter part of the Civil War in 1923 were also relatively quiet spans, revealing considerable variance in the intensity of the revolution as measured by the number of fatalities. But each death was not simply a statistic; it directly affected close family members and other relatives, not to mention friends and neighbours of the deceased. To provide this context and other personal data we have supplied as much relevant information as possible for each entry.

Objectives and Methods

The primary objective of this fatality register is to identify as far as possible those killed in connection with the conflict, as there remains uncertainty with regard to some of the fatalities, and a number of those killed no doubt remain unidentified. Identification of deaths is not always a straightforward matter, for while an incident where people were badly wounded might have been recorded in the press, the subsequent fate of the casualties is frequently not at all clear.1

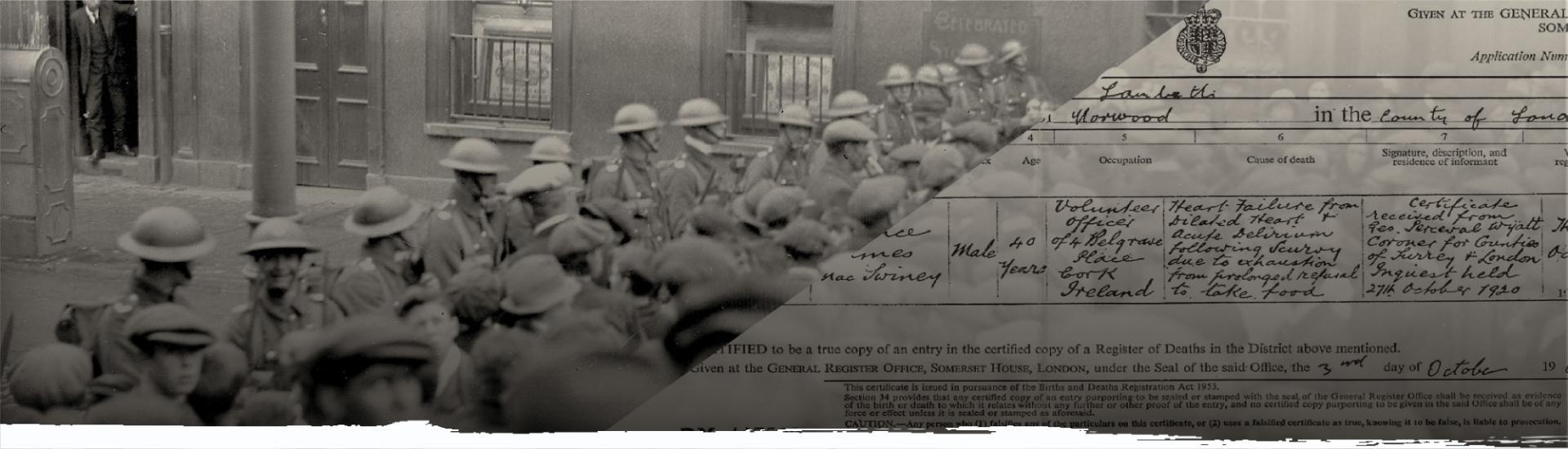

Though we have gathered data based on the registration of deaths by the state—a task taken over in 1920 by the British Army in County Cork, which became the director of ‘military inquests’—this procedure was by no means comprehensive and could be subject to military interference and even to omissions in cases where crown forces were directly involved. A wide range of other sources were consulted to bridge this deficit, and these often provided conflicting accounts of the circumstances of death, reflecting the biases of the protagonists or the purpose for which a given type of source was created. Republican memory of major ambushes, for example, dramatically exaggerated British fatalities in many instances. Compensation claims were shaped primarily to secure monetary awards within the terms of reference of the claim pursued; newspapers might have reflected the political biases of their editors or correspondents; IRA and crown-force sources commonly presented conflicting or contradictory perspectives. Moreover, numerous sources were gathered decades after the episodes in question. These delays frequently helped to give rise to multiple interpretations of the same death.

We have attempted to ascertain details of the initial incident leading to any given death; we have also recorded the contemporary description as well as the date, time, and location of each death (as far as possible). The victim of an ambush or shooting, for example, may have been fatally wounded in one location of the county but then died weeks later in a hospital at another location. We have highlighted the former incident (as the site of the violence which led to death), while also taking note of the latter where possible. We have accounted for deaths resulting from wounds at the place and date of wounding (e.g., an ambush site) rather than at the place of death (e.g., a hospital or prison). We indicate executions at the place of execution.

Each of the entries in Cork’s Fatality Register follows the same format:

- (1) the name of the deceased, including certain variations in the forename or surname that appear in the sources;

- (2) the victim’s age (if known, and usually as derived from the 1911 census);

- (3) the victim’s residence if known—given without parentheses;

- (4) the place of death, given within parentheses;

- (5) the exact date of the incident, i.e., the date on which the victim was killed or mortally wounded, or the date on which the victim was abducted or otherwise disappeared, though death took place on a later date;

- (6) the full range of our sources for each death, with abbreviations as needed, and for which a full list will soon be supplied on the website as part of a comprehensive bibliography; and

- (7) a note providing all valuable information about the victim available to us and considered relevant.

About the Researchers

Andy Bielenberg is a Senior Lecturer in the School of History, University College Cork, where he lectures on Irish social and economic history in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He also teaches about and undertakes research on the First World War, the War of Independence, and the Civil War, with a special focus on County Cork. He received his doctorate from the London School of Economics in 1992. His recent publications include Ireland and the Industrial Revolution, 1801-1922 (2009), which summarises many years of research on Irish industrial history; An Economic History of Ireland since Independence (2013), co-authored with Raymond Ryan; and “Exodus: The Emigration of Southern Irish Protestants during the Irish War of Independence and the Civil War,” Past and Present, no. 218 (Feb. 2013).

James S. Donnelly Jr is Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he taught modern Irish and British history from 1972 to 2008. He authored The Land and the People of Nineteenth-Century Cork: The Rural Economy and the Land Question (1975) and The Great Irish Potato Famine (2001). He co-edited (with Samuel Clark) Irish Peasants: Violence and Political Unrest, 1780-1914 (1983) and (with Kerby Miller) Irish Popular Culture, 1650-1850 (1998). His latest book Captain Rock: The Irish Agrarian Rebellion of 1821-1824 was published in the fall of 2009. He serves as co-editor (with Thomas Archdeacon) of the book series ‘The History of Ireland and the Irish Diaspora’ at the University of Wisconsin Press (20 volumes published to date). He was co-editor of the journal Éire-Ireland from 2001 through 2017 and has served since then as senior consulting editor.