In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

The Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920: A night of terror and destruction

Three new interactive maps designed and developed by UCC cartographers Charlie Roche and Mike Murphy, offer new perspectives on the so called ‘Burning of Cork’ by Crown forces on 11-12 December 1920.

In what the Cork Examiner called ‘a night of horror’, the burning of Cork on 11-12 December 1920 was the most devastating of the Crown force reprisals during the Irish War of Independence. Fifty-seven premises at the heart of the southern capital were destroyed by fire, twenty were badly damaged and twelve were wrecked and looted. Five acres of property – the equivalent of about three football pitches – were involved. While there was no loss of life as a result of the fires, some £2.5m worth of damage was caused and over 2,000 people lost their jobs.

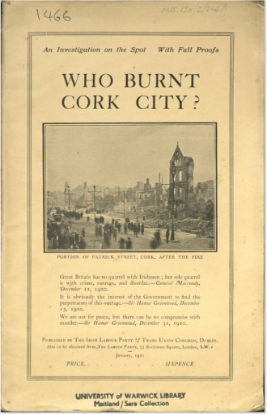

This first of three interactive maps provides a visual overview of the buildings destroyed, damaged and looted on 11-12 December 1920. Based on new research, it builds on a map published by the Irish Labour Party and Trade Union Congress in their pamphlet Who burnt Cork city? A tale of arson, loot and murder (January 1921).

Zoom into the map to discover the proprietors and residents of the affected properties in 1920 as well and images of the scenes of destruction from the Irish Examiner archives and Cork Public Museum.

Click here to view the map in full screen.

If you are having trouble viewing the map, please ensure that your web browser settings are not blocking "Third Party Cookies."

Far from being an isolated incident, the devastation of the city centre was the culmination of an intense period of arson, intimidation and looting during the autumn of 1920. This second interactive map, built on the 25 inch historical Ordnance Survey maps of Cork city hosted by the Department of Culture Heritage and the Gaeltacht, locates the key actions and events that took place in Cork city between January and December 1920. Mapping the attacks and counter attacks, ambushes and reprisals demonstrates the extent to which the city was in the grip of what Bishop Daniel Coholan would call a ‘devils competition between the IRA and agents of the Crown.’ By December 1920, Cork city was a tinderbox of violence just waiting for a spark.

Zoom into the map and click on the labelled locations to discover more about what happened in Cork in the months leading up to the Burning of Cork.

This map was designed and produced by Charlie Roche (MobileGIS, associated cartographer/researcher for University College Cork’s Atlas of the Irish Revolution)

Click here to view the map in full screen.

If you are having trouble viewing the map, please ensure that your web browser settings are not blocking "Third Party Cookies."

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

The spiral into violence began in earnest in March when the shooting of RIC District Inspector McDonagh on Pope’s Quay was followed by the assassination of the city’s first republican Lord Mayor, Tomas MacCurtain at his home in Blackpool. Then, on the first weekend in April, to coincide with the anniversary of the Easter Rising, IRA GHQ ordered a major mobilisation by the Irish Volunteers for a concerted nationwide assault vacated police barracks, courthouses and tax offices. On the 5 April, 1920, tax offices on the South Mall and the South Terrace, as well as others outside the city were targeted by the IRA.

Tensions heightened again with the arrival of the Black and Tans in the Spring and the number of fatalities on both sides increased. The ceaseless round of searches, patrols and arrests went hand in hand with intimidation and harassment of the civilian population.

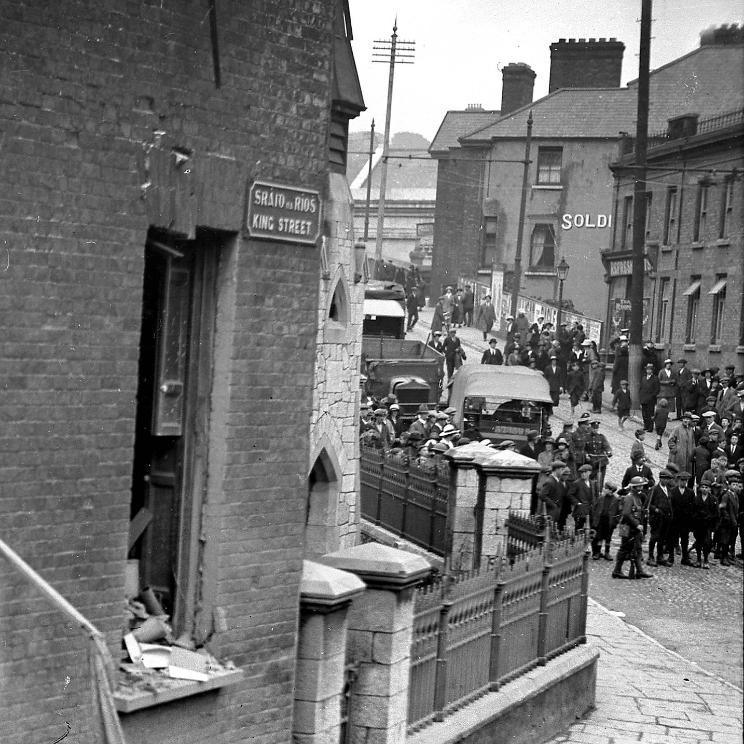

King Street (MacCurtain Street) RIC barracks after it was attacked and destroyed by Cork No.1 Brigade IRA on July 20th. 1920. [Source @Irish Examiner]

On 12 July the IRA burned out three RIC barracks in the city at King Street (MacCurtain Street), St Luke’s and Lower Glanmire Road. Six days later, on 17 July, Divisional Commissioner G. Brice Ferguson Smyth shot dead by the IRA at the County Club, South Mall. This prompted the introduction of a curfew in the city after which anyone caught on the streets after 10pm within a three miles radius of the GPO on Oliver Plunkett Street could be arrested. August saw the arrest at City Hall of Terence MacSwiney who had replaced his friend and commander, Tomas MacCurtain as Lord Mayor. MacSwiney was lodged in Cork men’s gaol near UCC where he immediately joined a hunger strike.

On 22 August members of Cork city IRA assassinated District Inspector Swanzy in Lisburn. Swanzy had been implicated in the murder of MacCurtain in March and relocated to the northern city for his own safety. The assassination prompted two days of rioting, arson and looting which the Belfast Newsletter compared to ‘an episode in Dante’s inferno’. The Irish Linen Centre & Lisburn Museum online exhibition, ‘The Swanzy Riots 1920′, features an interactive map by Charlie Roche based on a database of more than 300 compensation claims.

Events in the autumn of 1920 turned up the temperature in Cork even further. The death of Terence MacSwiney in Brixton prison after 74 days on hunger strike was reported all over the world. His body was returned to Cork and tens of thousands of people filed through City Hall where he was lying in state. MacSwiney was buried in Finbarr’s cemetery on 1 November, the same day that 18-year-old medical student Kevin Barry was executed in Mountjoy.

Prior of the autumn of 1920, Cork city had largely escaped the attacks on property that constituted the unofficial policy of Crown Force reprisals. Between June and September 1920 the national and international press was outraged by the destruction of centres of population such as Tuam, Thurles, Mallow and most notably, Balbriggan in Dublin. The campaign of reprisal attacks on property came forcibly to Cork in the autumn and winter of 1920. On 3 October Cork city Volunteers staged an ambush from Blackthorn House on the corner of Princes Street and Patrick Street. Three Black and Tans were wounded and a fourth died from his wounds in the military hospital in Victoria Barracks. Five days later a British soldier was killed in an ambush on Barrack Street. Retribution was directed at the municipal heart of the city and were it not for the swift arrival of the Cork Fire Brigade, Cork City Hall would have been completely destroyed.

Another notable event during October was the decision by General Crozier to form a new company of Auxiliary cadets and station them in Cork city. The sixty-seven men of the notorious ‘K Company’ were placed under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Latimer and billeted in the gymnasium at Victoria Military Barracks. From the point of their arrival in late November, the levels of violence and intimidation in the city increased again. Florrie O’Donoghue later recorded that ‘their drunken aggressiveness became so pronounced that no person was safe from their molestations.’

Members of the Auxiliary Division, RIC, at Lower Glanmire train station (now Kent Station), Cork, circa 1920-1. [Source: @Irish Examiner]

This period also saw the establishment by the British Labour Party of a commission of inquiry into republican violence and reprisals by the forces of the Crown. On 25 October, Labour Party deputy leader Arthur Henderson told the House of Commons that, while outraged at the actions of the Sinn Féiners, he was appalled by what he described as the ‘a policy of military terrorism’ in Ireland. It was time, he said for an independent investigation into the ‘causes nature, and extent of reprisals on the part of those who duty is the maintenance of law and order’.

Back in Cork City, the arrival of new Auxiliaries failed to discourage the Volunteers. On 17 November, acting on intelligence delivered by civilian intelligence agent Josephine Browne in Cork Military Barracks, the IRA captured and executed three British intelligence officers in Waterfall just outside the city. Later that night RIC Sergeant James Donoghue was shot dead by three Volunteers as he was walking down White Street. It was no surprise that retaliation came swiftly. That evening two armed and masked men wearing police uniforms made their way to the tenement buildings and lane-ways of the area known locally as the ‘Marsh’. Their primary targets were the O’Brien brothers, who they suspected of being involved in the killing of Donoghue. The gunmen entered No 2 Board Lane where they killed seventeen-year-old Fianna Éireann member Patrick Hanley. Up the street at No 17, ex-serviceman, Eugene O’Connell was shot dead and Charlie O’Brien seriously wounded. Not long afterwards, at No 15 North Mall James Coleman, prominent member of the Cork Chamber of Commerce, was shot dead in front of his wife. On the same night, Roches jewellers on Patrick Street and O’Callaghan’s tobacconists on the North Mall were broken into and looted.

The pervasive sense of fear in the city was not lost on the Labour Commission delegation who arrived in Cork in late November to conduct interviews and visit the scenes of reprisal attacks. They reported,

The atmosphere in Cork prior to the latest acts of incendiarism was beyond description. During the time we were in the city terrorism was at its height. Cork has perhaps suffered longer from the brutal domination of ill-disciplined armed forces than any other town in Ireland … The whole of the civilian population has been in varying degrees under the terror.

This terror did not act as a deterrent to the Cork IRA who were busy making plans to abduct a senior British intelligence officer after mass on Sunday 21 November. However, in a case of mistaken identity they actually captured an RIC constable named Ryan on the steps of St Peter’s Church. Later that night, the security forces raided the homes of well-known republicans and shortly after midnight the extensive premises of Dwyer and Co. on Washington Street was looted and set on fire. This marked the beginning of a week-long spate of arson attacks in Cork city centre.

Unsurprisingly, early targets were Sinn Fein halls and GAA Clubs, synonymous with the republican cadre in the city. On 23 November, a bomb exploded on the corner of Princes Street and Patrick Street killing two Volunteers. Business premises were also burned and looted on St Patrick Street, MacCurtain Street and Bridge Street. This was compounded by reports on 28 November of the Kilmichael Ambush. The following day saw the Camden Quay headquarters of the ITGWU set on fire. As the city fire brigade struggled to control a fire at the Sinn Fein Club at Fr Mathew Quay on 30 November, they received word that there had been another attempt to raze the City Hall. Tensions were increased again on 2 December with the funeral parade for the Auxiliaries killed at Kilmichael passed through St Patrick Street. On the same day the officers of the Irish National Assurance company on Marlborough Street were set on fire.

On 6 December, Donal O’Callaghan summed up for the British Labour commission the extent of the disturbances in the city.

‘During the month of November alone over 200 curfew arrests had been made, four Sinn Fein clubs burned to the ground, twelve large business premises destroyed by fire, in addition to attempts made to fire others including the City Hall, seven men shot dead, a dozen men seriously wounded, fifteen trains held up, four publicly placarded threats to the citizens of Cork issued and over 500 houses of private citizens forcibly entered and searched.’

He could not have known that things were about to get much worse as the Cork IRA made plans to build on the momentum of the Kilmichael Ambush. This story map, developed by Charlie Roche, maps the the Ambush at Dillon’s Cross on the north side of the city on the evening of 11 December 1920.

Zoom into the map and click on the individual symbols to follow the steps leading to the burning of six houses at Dillon’s Cross by Crown Forces.

If you are having trouble viewing the map, please ensure that your web browser settings are not blocking "Third Party Cookies."

This map was designed and produced by Charlie Roche (MobileGIS, associated cartographer/researcher for University College Cork’s Atlas of the Irish Revolution)

Click here to view the map in full screen.

THE BURNING OF CORK

As the first reprisal attacks of the night were taking place at Dillon’s Cross, people were busy trying to get off the streets before curfew at 10pm. According to witnesses statements collected by the Irish Labour party in the aftermath of ‘the Burning of Cork’, a group of Auxiliaries proceeded from St Patrick’s Bridge down Patrick Street at about 9.30, smashing shop windows and firing indiscriminately. One of the most valuable eyewitnesses to the events of 11 -12 December, was Alan J Ellis – a young reporter with the Cork Examiner. At about 9.30 he left his cousin’s home at Cornmarket Street to make his way to the Examiner offices on Patrick Street, hoping to hitch a ride home on a colleague’s motorbike. On turning into St Patrick Street from Castle Street he realised that something unusual was happening.

I could hear sporadic rifle fire and small arms from every direction. At first I thought it was an engagement between republicans and the military. Then I noticed, further down Patrick Street the ‘Auxies’ and soldiers were driving people from the streets and firing over their heads to make them disperse into the buildings. Grant’s drapery store appeared to be on fire.

Alexander Grant and Co, an upmarket department store on Patrick Street was the first of the large commercial premises targeted by the Auxiliaries. Making his way up Patrick Street, Ellis was joined by a man who swore that he saw a patrol of Auxiliaries break into Grants and set it ablaze. In the meantime, a motor ambulance had been dispatched from the Grattan Street fire station to Dillon’s Cross. It turned into Patrick Street and was met with scenes of pandemonium. One fireman recalled

We stopped on seeing between forty and fifty civilians, well dressed walking in a body in the middle of the road. … ‘Where are you going to? I was asked. In my opinion the speaker had an English accent. I replied, ‘To Sullivan’s Quay, to turn out the fire brigade’. A man answered me, ‘All right. Take your time, you’ll have a few more in a minute’…

At 10.20 Fire Chief Alfred J Hutson received word that Grant’s was on fire. Without the manpower or the equipment necessary to deal with the situation, he contacted Victoria Military Barracks for assistance in outing the blaze. Unlike on previous occasions, his request was ignored. Hutson was forced to abandon plans to tackle Dillon’s Cross and lead his men to St Patrick Street where the fire in Grant’s had made considerable headway. At about 11.30 Huston learned that the Munster Arcade and Cash’s department store were on fire.

Eyewitness Peter Barry, an apprentice living in an apartment over the Munster Arcade, testified at a compensation hearing that the police tore a door off the building and then threw a bomb inside, which exploded in the shop beneath him. Without waiting to gather clothes or belongings, he and the other men and women in residence over the Arcade made their way out though the side entrance on Elbow Lane where they were harassed by auxiliaries. Chaos now reigned as civilians ran for shelter and the firemen made heroic efforts to fight the growing conflagration. In spite of their best efforts, most of the south side of St Patrick’s Street was on fire by 11pm. The blaze from Cash’s had spread to the Lee Cinema, Roches Stores, the Lee Boot Company, Connell and Company, Scully’s, Wolf’s and O’Sullivan’s. The block above the Munster Arcade was also on fire by the early hours of the morning.

Accounts of the burning provided by firemen suggest that they were subject to intimidation, attempts were made to impede their progress, and some were even fired at, narrowly escaping serious injury. According to one fireman who took part in a 1960 RTE documentary on the Burning of Cork:

We were useless. They were cutting the hoses and they were firing all around them. There was one man … on top of Cash’s up a ladder. He was ordered down by a Black and Tan with a bomb in his hand. …. He was told that he would either get this or get down, and that meant that fire went on. It was worse than if a fellow was out in Flanders, or any other battlefield.

From his vantage point on the roof of the Shamrock Hotel on the Grand Parade, Volunteer Michael O’Donoghue recalled the terrifying spectacle.

Billows of red flame roared and swelled high into the air about 200 yards north east of us. … As we watched the devouring flames, awe-struck and fascinated, our backs and bodies generally shivered in the cold frosty air of the roof; but, turning our faces to the red-roaring holocaust, we felt the heat-waves beating against our faces. It was an extraordinary experience.

The night of incendiarism was not over. Alan Elis, who had made his way to Anglesea Street, found a unit of the city fire brigade actually pinned down by gunfire. When he asked who was firing on them, they said it was Black and Tans who had broken into the nearby City Hall next to the station.

One fireman told me that he had also seen ‘men in uniform’ carrying cans of petrol into the Hall … Around four o’clock there was a tremendous explosion. The Tans had not only placed petrol in the building but also detonated high explosives. The City Hall and adjoining Carnegie Library with its hundreds of priceless volumes was suddenly a sea of flames …They turned off the fire hydrant and refused to let the fire crews have any access to the water. Protests were met with laughter and abuse. Soon after six o’clock the tower of the City Hall crashed into the ruins below.

Incredibly, there was no loss of life as a result of the fires, but 2am, as Patrick Street was burning, members of the crown forces entered the home of the Delaney family on Dublin Hill and shot brothers Jeremiah and Cornelius, both of whom were members of the IRA. Their father, Daniel later provided a witness statement to the Irish Labour party inquiry.

At least eight men entered the house and went upstairs. A large number remained outside, as I could hear them moving and see them in the yard. The men who went upstairs entered my sons’ bedroom, and said in a harsh voice, ‘Get up out of that’. … My sons got up and stood at the bedside. They asked them if their name was Delany. My sons answered, ‘Yes’. At that moment I heard distinctly two or more shots, and my two boys fell immediately.

Funeral of Cornelius Delaney passing the ruins of a devastated St Patrick’s Street [Source: Irish Examiner]

Fire men continued to battle the fires well into Sunday as the city’s people emerged to examine the applying destruction to the proud eighteenth-century thoroughfare. In a poignant diary entry for 12 December, Sinn Fein TD for Cork city, Liam de Róiste described ‘an orgy of destruction and ruin’.

Last night in Cork was such a night of destruction and terror as we have not yet had. An orgy of destruction and ruin. The calm sky frosty red – red as blood with the burning city, and the pale cold stars looking down on the scene of desolation and frightfulness. The finest premises in the city are destroyed, the City Hall and the Free Library..

Many years later, Florrie O’Donoghue, recalled the searing grief of seeing his city so scared:

Many familiar landmarks were gone forever – where whole buildings had collapsed, here and there a solitary wall leaned at some crazy angle from its foundation. The streets ran with sooty water, the footpaths were strewn with broken glass and debris, ruins smoked and smouldered and over everything was the pervasive smell of burning.

Corkonians move through the ruins of the Munster Arcade on St Patrick’s Street [Source: Irish Examiner]

Those citizens who attended 12 o’clock mass in Cork’s North Cathedral on Sunday morning were witness to a hard hitting sermon from their Bishop, Daniel Coholan, who denounced the murderous violence on both sides. In the face of the destruction of Patrick street, which he compared to scenes from Dublin after the 1916 Rising, he considered it his duty to deal harshly with the perpetrators of violence in the city.

If any section of the Volunteer organisation refuse to hear the church’s teaching about murder, there is no remedy but the extreme remedy of excommunication from the church. And I will certainly issue a decree of excommunication against anyone who, after this notice, shall take part in an ambush or a kidnapping or attempted murder or arson.

For many devout Catholic Volunteers the decree was deeply unsettling. For an apoplectic J.J. Walsh, speaking at a specially convened meeting of the Corporation that afternoon, the bishop was ‘adding insult to injury’. He was afraid that Coholan’s utterances may be used to ‘blackmail the Irish people, and hold them up as the evil doers’ rather than those who were responsible.

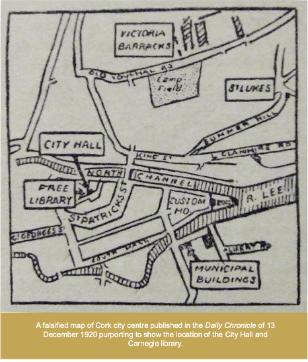

This was certainly the line taken by Irish Chief Secretary, Sir Hamar Greenwood during the House of Commons Debate on 13 December. In response to questions about the authorship of the crimes in Cork, Greenwood protested ‘most vigorously against the suggestion without any evidence, that these fires were started by forces of the Crown’. His oblique reference to the fact that Sinn Féiner’s rather than the Crown forces were in possession of the incendiary devices used in the burning of Cork, suggested that the people of Cork had burned their own city. He also countered the chorus of appeals for an independent inquiry by assuring the House that a military inquiry, more appropriate in the context of martial law, had been initiated by General Strickland in Victoria Barracks. The Chief Secretary went on to strongly condemn the comparison made by one MP between the German sacking of Louvain during World War One and the burning of the City Hall and Carnegie Library in Cork. ‘I see a great difference, he said, ‘between firing a building and its being burned down by the spread of a conflagration’. The outrageousness of the Chief Secretary’s theory was reinforced by a falsified map of Cork city center published in the Daily Chronicle on the same day.

‘The Irish Louvain’ – a view of the ruined remains of St Patrick’s Street following the ‘Burning of Cork’ on 11–12 December 1920. [Source: National Library of Ireland, HOGW 100].

The vast majority of the Irish and British press, however, were in no doubt about the perpetrators of the Cork city reprisals. As a photograph of Patrick Street in the aftermath of the burning went around the world with the provocative title, ‘the Irish Louvain’, the Manchester Guardian reported:

This is a reprisal – the worst that has yet occurred in Ireland and there can be little doubt that this appalling-destruction is the crowning sequel of a long series of incendiary fires by which servants of the Crown sought to terrorise the city and crush its militant Sinn Fein.

A Cork Examiner editorial on 14 December dubbed the suggestion that the fire had been started by the people of Cork as ‘outrageous’ and a ‘malicious insinuation’, which would be given little credence. The Irish Independent of the next day described the general ridicule and amazement at Greenwood’s suggestion. ‘Even staunch Unionists’, it reported, ‘do not deny that all the evidence available points to only one conclusion.’

General Strickland was clearly in no doubt about where the blame lay as he promptly dispatched K Company to Dunmanway in West Cork where they continued to wreak havoc on the local population. Certain too were the 73 eyewitnesses who provided testimony to the Irish Labour Party’s inquiry. Their anonymous statements were compiled and published as a booklet entitled ‘Who Burnt Cork City,’ over 2,000 copies of which were sold by March 1921.

On 14 December, Cork Corporation issued a telegraph to Westminster repudiating most emphatically the vile suggestion that city was burned by any section of the citizens and demanding an impartial civilian inquiry. The only state-sanctioned inquest however was the enquiry conducted by Major General E. P. Strickland, the Military Governor of the Martial Law Area. Starting on 16 December, the enquiry lasted five days and took statements from thirty eight witnesses. The report, which found that the members of the Auxiliary Division of the RIC were responsible for the fires, was placed before cabinet on 4 January 1921 and two weeks later the decision was made to quietly suppress the document.

In the meantime, the American Commission on Conditions in Ireland continued its public sessions in Washington D.C. with testimony from Cork’s Lord Mayor, Donal O’Calaghan, who had bypassed British passport restrictions by stowing away on a steamer bound for America. His statement dealt with the devastation of 11 December which he emphatically attributed to the British security forces who were the responsibility of the the British Government. His testimony was undoubtedly influential in the Commission’s damning indictment of the of the Crown forces’ behaviour in Ireland as ‘organised anarchy’.

Some of the Influential Irish-American members of the Commission were also founding members of the American Committee for Relief in Ireland (ACRI), established five days after the burning of Cork. Early donations to the ACRI meant that they were ready in January to send money to Belfast and Cork and needed a conduit in Ireland. This accelerated Sinn Fein’s plans for an Irish White Cross organisation, which was officially established on 1 February 1921.

Over six weeks in February and March 1921, an ACRI delegation visited 95 Irish locations and identified an estimated 100,000 people in urgent need of relief. By July over 1.2 million dollars had been sent to Ireland for disbursement by the Irish White Cross.

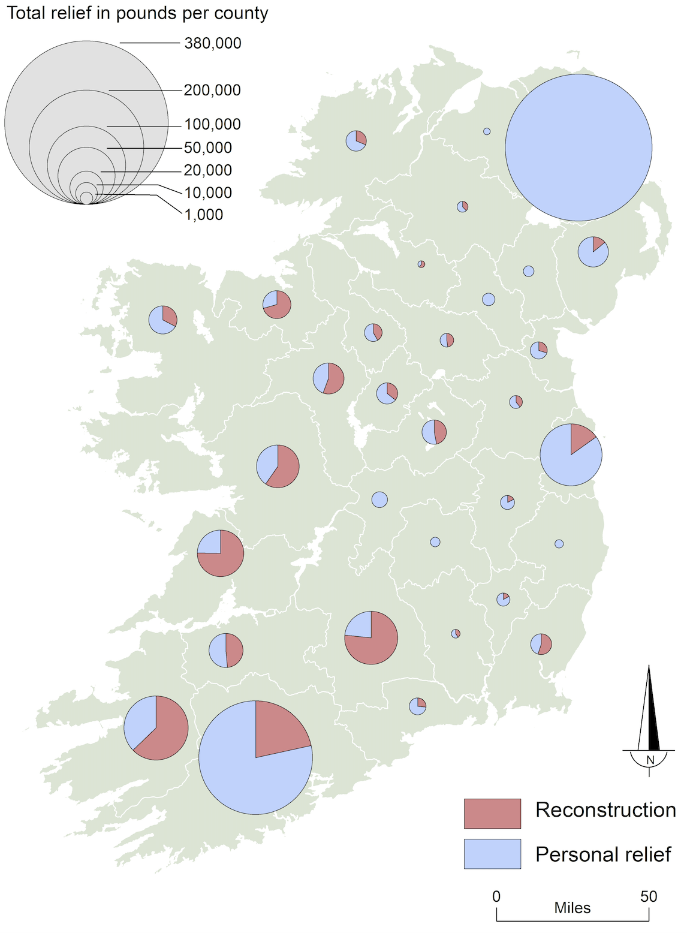

The Disbursement of funds by the Irish White Cross by county. [Source: Atlas of the irish Revolution (2017)]

This map, based on the Reports of the AIRC and the Irish White Cross in 1922, show how the funds were distributed by county in its two categories – Personal Relief and Reconstruction. Just over three quarters of the entire funds went to personal relief – that is to families and individuals who had suffered unemployment injury or the loss of the breadwinner. Most went to those affected by the ‘pogroms’ and workplace expulsions of the Catholics in Belfast, and to the victims of the burning of Cork. The huge amount of personal relief reduced the amount available for reconstruction.

Belfast received £362,356.16.1 in Personal Relief and Cork, £170,398.3.9. Cork city and county were the leading recipients of Reconstruction funds – £47,090, followed by Kerry (£43,625) and Tipperary (£36,431). Cork city and county were the leading recipients of reconstruction funds (£47,090).

– Maps designed and developed by Charlie Roche and Mike Murphy. Context by Helene O’Keeffe –