In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

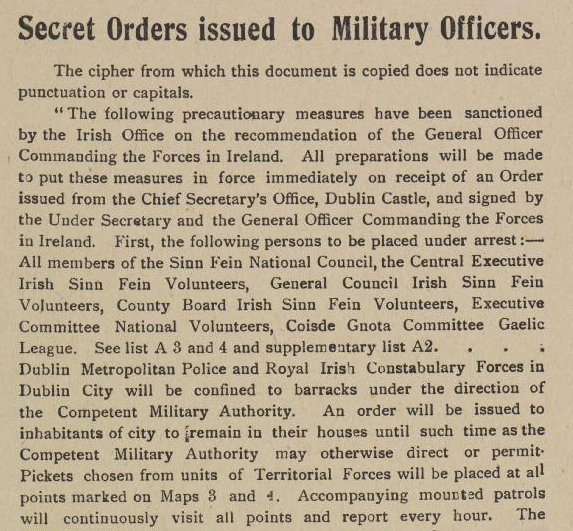

The Castle Document could have altered the Rising writes Bill McCormack

A small printing press in the home of Joseph Plunkett was responsible for one of the most controversial documents in Irish history.

Intended to deceive those unaware of the intended rebellion to back the idea, it has come to be known as the Castle Document. But historians differ — and the full truth may never be known — as to how the content was decided or where it originated.

Seán MacDiarmada — Plunkett’s co-conspirator on the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) military council — had sources in the intelligence world, certainly.

But it is more likely that the content of the‘Castle Document was a composite of material secreted out from inside the British administration, and of the creative writing, probably, of James Plunkett.

The document suggested military raids were planned, at an imminent unknown date, in which arrests would be made of the officers of the Irish Volunteers, National Volunteers, and Gaelic League.

From a military perspective, the naming of certain addresses to be taken over meant the Volunteers and James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army were effectively being suppressed after months of police surveillance of their leaders’ every move. Those premises included Citizen Army and ITGWU headquarters at Liberty Hall, Irish Volunteers HQ at Dawson St, and other premises regularly named in daily ‘movement of extremists’ reports from Dublin police detectives.

Furthermore, communication was to be restricted in and out of the homes of Plunkett, Irish Volunteers chief of staff Eoin MacNeill, Constance Markievicz, and Padraig Pearse’s St Enda’s College, among other locations.

The document was distributed to newspapers over the weekend of Saturday and Sunday, 15 and 16, Palm Sunday, 1916 — but there was little take-up by editors, probably under fear of wartime censorship.

It was not until a copy found its way into the hands of Dublin Corporation member Tom Kelly, and he read it to the council on Wednesday, April 19, that it eventually became public.

The reaction was mixed: Many people, on reading reports of the document, believed Dublin Castle’s claims that it was bogus (a focus on Dublin City only instead of the whole country, and highlighting printing anomalies helped bolster the argument).

But the senior IRB men managed to convince MacNeill of the need to place regional and local commanders around the country on notice to defend their arms with force if necessary.

He had been unaware of the secret plans to launch a rebellion on Easter Sunday. But it was his willingness to back the Rising in light of this information — and on finally learning of the planned Rising on Good Friday, April 21, 1916 — that led to the confused orders emanating from Irish Volunteers headquarters in the lead up to Easter weekend.

In Cork, for example, Brigade commandant Tomás MacCurtain received no fewer than nine messages from Dublin — some from Seán MacDiarmada and Padraig Pearse of the IRB military council — up to Easter Monday.

The news that reached Dublin on Saturday — of the Aud and its cargo of guns from Germany being arrested and sunk off the south-west coast — had eventually convinced him to issue the infamous countermanding orders. By despatches around the country and a notice placed in the Easter Sunday edition of the Sunday Independent, he effectively ensured a far lower turnout than might otherwise have been expected of Irish Volunteers for the rebellion that was to have kicked off that evening.

The Rising did, however, eventually begin— almost 24 hours later than planned — on Easter Monday, April 24, 1916.

Bill McCormack’s forensic analysis of whether — or to what extent — the Castle Document was a forgery is in Making 1916 — Material and Visual Culture of the Easter Rising, edited by Lisa Godson & Joanna Bruck (Liverpool University Press, 2015).