In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Released Files Show President Higgins Family Diversity in 1916

President Higgins’ family illustrates just how divisive the Civil War was, as siblings nationwide chose to fight on opposite sides, writes Niall Murray, Irish Examiner

President Michael D Higgins’ family show just how divisive the Civil War was, as his father and uncle went different ways over the 1922 Anglo-Irish Treaty, while their two siblings appear to have remained neutral. The details emerge in files released in relation to their applications for pensions in respect of their military service during the Irish revolution. The four Higgins siblings’ files are among those of 882 people whose actions in the 1916 Rising, the War of Independence, or the Civil War — and in some cases all three — have been scanned for the Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) since last June. Their public availability through the website of the Military Archives mean that MSPC files so far uploaded cover applications for pensions, allowances and medals of nearly 4,800 individuals — with further releases planned in the coming years.

As a boy, President Higgins, who was born in 1941, was cared for by his uncle and aunt in Co Clare. His father, John Higgins, had moved from Co Clare to north Cork in the early stages of the 1919-1921 War of Independence. But while he fought with the anti-Treaty IRA in the 1922-1923 Civil War, his brother Peter joined the Free State Army to oppose the side that John had taken. John Higgins initially served with the Ballycar company (D company) in the 1st Battalion of the Irish Volunteers/IRA East Clare Brigade from around 1918. He later transferred to the Charleville company in Cork No 2 Brigade (north Cork) 4th Battalion, where he served as a company lieutenant from March 1920 and was involved in an attack on Freemount Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks. He also claimed to have blocked roads when the IRA attacked barracks in Ballylanders and Kilmallock, both just inside the Co Limerick border, cutting roads on the Buttevant road on one occasion. For John, like hundreds of IRA volunteers and officers in that period, other duties included raiding mails, cutting telegraph wires to disrupt Crown Forces communications, and moving arms around the local countryside.

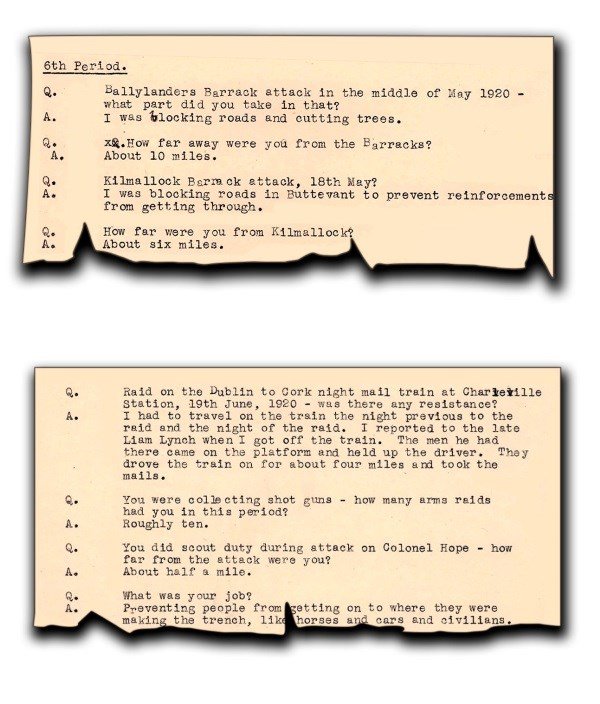

Extracts from the transcript of the 1936 interview of John Higgins, father of President Michael D Higgins, in relation to his military service pension application. Pic: Military Archives, Military Service Pensions Collection

In the months leading up to the July 1921 truce in the War of Independence, as the military campaign by both sides intensified, so too did the activities of John and his fellow IRA members. Some incidents in which he was involved were a May 1921 raid for mail at Charleville Post Office, when he carried a revolver, and burning a house of Lord Kenmare and another used by the British Legion, both of which were said were to be about to be occupied by British forces, only weeks out from the truce. During the same period, two local men suspected of giving information on the IRA to Crown Forces were sentenced to death and executed in June. According to his 1951 petition relating to a previously refused application, John Higgins was battalion intelligence officer in that part of north Cork from September 1921. During the Civil War, he was with an IRA Flying Column involved in two ambushes on Free State soldiers. He told an advisory committee assessing pension applications in 1936 that he also spent time organising men in local companies to gather information on the Free State army. John spent most of 1923 in custody, having been arrested in January and interned until December in Limerick and in the Curragh camp where anti-Treaty IRA members were held. He outlined in a 1935 addendum to his application how hard it was to get work after being interned. His work had suited him to intelligence work, having been employed as a grocer’s assistant in Charleville on a good salary of €130 a year, plus €50 for travel. However, after his release a local deputation had to approach Owen Binchy and Sons to take him back on.

“He refused to do so, with the result that I was idle until the 1st of August 1924 when I got a position as a junior assistant from Michael Nolan, Eyre St, Newbridge, at a salary of €50 per year,” he wrote in support of his claim. “At the time very few people would employ an ex-internee.”

John was awarded a pension for four and 3/8 years of military service at Grade E level, but only after appealing the earlier refusal of his claim.

Peter Higgins, meanwhile, was a lieutenant in the Ballycar company in east Clare, and was a member of the Brigade Flying Column during the War of Independence. During the Civil War, he enlisted in the Free State Army and served as sergeant in the headquarters company of 4 Infantry Battalion in the 1st Western Division.

“When the split came, he stood loyal and joined the army on its formation. Again I found him to be one of the most reliable men I had in Galway and would trust him to any extent,” wrote an Army colonel in a 1925 reference.

Peter received a pension for a period of seven years’ service under the 1924 Army Pensions Act. Michael Higgins, also serving with the Ballycar company, was involved in work on Éamon de Valera’s hugely significant East Clare by-election campaign as Sinn Féin candidate soon after joining the Irish Volunteers in May 1917. So too did Kitty Higgins, in her role as a recent recruit to the local Cumann na mBan branch. But despite an extensive list of activities throughout the War of Independence, including scouting, carrying despatches, supplying tools, and blocking roads, Michael had to wait more than four years after seeking a pension in late 1935 to be told his service did not qualify him for payment. Under the relevant pensions acts at the time, the interpretation of active service did not cover such work. There was a similarly unsuccessful outcome to Kitty’s pension claim at the same time, in which she had outlined a long list of activities, supported by references from local IRA officers. Like many Cumann na mBan members in rural Ireland, she fed and housed volunteers on the run from British forces, carried IRA despatches, and brought food to men sleeping in the countryside.

Asked in an interview by the pensions advisory committee in June 1940 if she took any part in the Civil War, she explained her predicament, one felt in hundreds of homes around the country.

“No, because I had one brother went one way and another went the other way,” she replied.

This article was first published in the Irish Examiner on 11 December 2015