In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Cork Hunger Strike, 1920

Dr Gabriel Doherty explores a traumatic episode in the long history of Cork city, which became a focal point for republican pride and anger during the War of Independence.

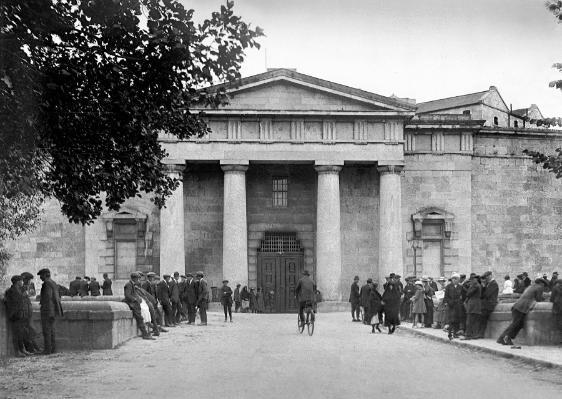

‘The prisoners in Cork Gaol started a hunger-strike at dinner-time today, demanding immediate release. Between 58 and 60 prisoners are on hunger strike.’

This insert in the ‘Late News’ column of the Evening Echo of Wednesday 11 August was the first confirmation to the outside world that a hunger strike had commenced in Cork men’s gaol on the Western Road in the city. The strike would ultimately last 94 days, result in the death by starvation of two of the prisoners involved – Michael Fitzgerald and Joseph Murphy – and permanent damage to the health of nine other men who, along with Fitzgerald and Murphy, constituted the eleven who were at the core of the action. It was, by any standards, a remarkable event, one of the longest such strikes in prison history anywhere in the world, a traumatic episode in the long history of Cork city, and a focal point for republican pride and anger during the War of Independence.

And yet it remains an under-studied, and for many an unknown, episode, notwithstanding the determined efforts made to mark the centenary of the strike. While several reasons can be put forward for this state of affairs, the most important was certainly the simultaneous hunger strike in Brixton prison, London, by the-then Lord Mayor of the city Terence MacSwiney, whose fast over 74 days undoubtedly generated global headlines, and to a certain extent over-shadowed, though it never eclipsed, the longer, larger action in his native city.

Hunger striking as a political tactic had, of course, been pursued by suffrage movement, albeit it was also widely-known in Ireland to have been practised during the pre-Norman era. The death, huge funeral, and damaging inquest, of the republican leader Thomas Ashe in 1917 following force-feeding in Mountjoy gaol had alerted the Government to the potential harm that could arise from a mis-handling of such a strike. Since then the authorities had initially granted striking prisoners ameliorations from ordinary prison discipline as a means of persuading them off the strike, and then, following the Mountjoy strike in April, formally introduced a category of political prisoner (albeit narrowly defined) to the same end.

When the Cork prisoners began their action, therefore, there seemed little reason to believe that the strike would not be resolved swiftly. On this occasion, however, the authorities struck a different note and from the beginning stated that the men’s demand – for a general, immediate and unconditional release – would not be granted in any circumstances. The stage was set for the ensuing tragedy.

The first few days of the strike saw the numbers involved fall significantly, partly through the release of those against whom little or no evidence existed, and partly by the transfer of others to English gaols. Terence MacSwiney – who, along with a significant proportion of the staff of Cork no 1 Brigade, had been arrested during a raid on City Hall the day after the strike began in the gaol – was one of this number, being despatched to Brixton after his court-martial conviction, his hunger strike already having commenced during his incarceration in Cork. Interestingly, the remaining brigade officers were among those released – an indication of just how poor Crown intelligence was at that point.

If the plan of those in authority was that the reduction in the numbers involved, and the fact that many of the deported prisoners ate before their journey (as sanctioned by IRA practice), would break the spirit of those who remained, their expectations were dashed. So it was that the final figure of eleven strikers became known just after the end of the first week of the strike. They, and their alleged offences, were:

- Michael Fitzgerald, Fermoy, co. Cork – alleged to have been involved in the killing of a soldier in Fermoy, county Cork on 7th September 1919

- John Power, Cashel, co. Tipperary – captured by soldiers on 2nd August 1920, allegedly in the course of preparing an ambush at Fethard, county Tipperary.

- Thomas Donovan (Emly, co. Tipperary), Mathew O’Reilly, John Crowley, Peter Crowley, Christopher Upton (all Ballylanders, co. Limerick) – arrested 16th August 1920, allegedly for having engaged in an ambush of police in Ballylanders on that date.

- Michael Burke (sometimes Bourke), Folkstown, Thurles, co. Tipperary – arrested August 9th 1920 for possession of a revolver.

- Seán Hennessy, Limerick – arrested 28th July 1920 on suspicion of having been involved in an ambush at Inchimore on 23rd July.

- Joseph Murphy, Pouladuff Rd, Cork city – arrested 17th July at his home and charged with possession of a bomb.

- Joseph Kenny, Grenagh, co. Cork – arrested 13th June, and charged with possession of a service rifle and ammunition.

Over the course of the following three months the strike followed a meandering path, occasionally veering towards optimism, but, especially after mid-September, seemingly inevitably set for a fatal end. There was a brief period, in the first fortnight of that month, when it seemed some movement was possible, as a result of the efforts of Harold Philip Barry, a local unionist and former High Sherriff of Cork. He showed great energy in cabling a number of prominent figures – including Prime Minister Lloyd George, Chief secretary for Ireland Greenwood and Neville Macready, Commander in Chief of the British Army – seeking a review of the cases of several of the men where genuine doubt seemed to exist as to their guilt. Despite the fact that his efforts were publicly repudiated by the prisoners, who insisted they would not accept a partial release, Barry placed the entire blame for the impasse at the feet of the Government.

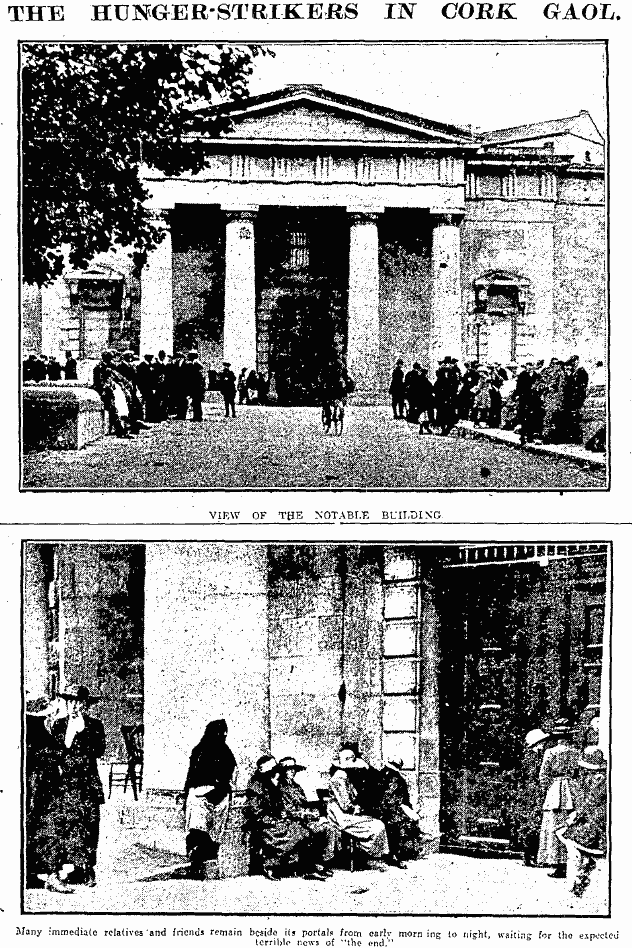

Images relating to the hunger strike featured in the Cork Examiner, 1 September 1920

This note of intransigence had been struck from the outset by Andrew Bonar Law, the hard-line unionist and leader of the Conservative party who was the public face of the government when the strike broke out, with Lloyd George on holiday in Switzerland. It was confirmed a fortnight later by Lloyd George himself, who said that release of prisoners simply because they resorted to hunger strike would completely undermine the judicial and penal systems, and would be a devastating blow to the Crown forces then facing an increasingly active IRA – and this remained the government’s line throughout the strike. Interestingly, a public meeting of ex-RIC men on MacCurtain street in Cork on 10 September, came out strongly in favour of releasing the prisoners.

The hunger strike was suffused by an all-enveloping religiosity. A small number of Catholic clerics (mainly in England) publicly criticised the action as suicide, but the general weight of theological contributions in Ireland came down in favour of viewing the fast by the strikers as a soldierly-like giving of their lives for their country, rather than the taking of them. The prison chaplain was a daily visitor to all, along with a number of prominent ecclesiastics, including the Cork-born Archbishop Spence of Adelaide, who strongly criticised the government’s stance following his visit. From the very earliest days a large number of relatives and the people of the city gathered every evening at the gates of the gaol to pray the rosary for those inside, and the men themselves were reported to participate in same as long as they were able.

On three separate occasions – 24th August, 22 September and 15 October – universally-observed stoppages of work were organised by the city’s Civic and Labour Council so as to allow workers to attend masses for the strikers, and over the course of the strike a truly staggering number of masses for their intentions were sponsored by practically every firm, every residential area, and every public body and private organisation in Cork (and many well beyond). The occasional messages that passed between the Lord Mayor and the prisoners in Cork were likewise shot-through with religious imagery, with the juxtaposition of faith and fatherland in this excerpt from a cable from Cork to London on 8 October illustrative of the general trend: ‘Sustained in our struggle by the will of God, and fortified by your example and our confidence in one another, we await with calmness the issue – prepared for death if need be in the cause of the Republic. We gladly join with you in your prayer committing our people and our cause to the mercy of God.’

Other bodies also expressed their support for the strike, with the Cork County GAA Board to the fore. On the 27th August it was decided that the county hurlers would not travel to Thurles to play the Munster final against Limerick, and the following week the footballers likewise pulled out of a fixture against Mayo – with their opponents on both occasions publicly indicating their support for the Cork action. On the 7 September the Board postponed all GAA activity in the county ‘as a tribute to the great sacrifices those men [the hunger strikers] were making and the sufferings they were undergoing for the principles they held so dear,’ with this suspension extended following the board meeting on 2 November (during which the playing of rugby on the Mardyke ‘within earshot of the hunger strikers in the County Gaol’ was also reproved).

The deaths of Michael Fitzgerald on the 17th October and Joseph Murphy on the 25th of the month (the same day as Terence MacSwiney) came as a severe blow to all concerned, and gave the lie to the rumour circulated in government-supporting newspapers that the men were being surreptitiously fed by visitors to their cells. All three were given huge funerals (to Kilcrumper cemetery for the first named, and St Finbarr’s for the latter two), with MacSwiney’s not surprisingly being the largest. The conduct of all three was disrupted by the military, who placed severe restrictions on the size of the corteges and forbade any overt military displays by the Volunteers – and in so doing exacerbated the huge ill-feeling generated by the strike and deaths.

Terence MacSwiney’s funeral in Cork where more than 100,000 turned out to pay their respects.

Following public discussion as to the merits of persisting with the action in light of the certainty that there would be no change in government policy, the men were directed to come off the strike by Arthur Griffith on 12 November, on the basis that they had ‘sufficiently proved their devotion and fidelity, and that they should now, as they were prepared to die for Ireland, prepare again to live for her.’ All the men recovered from their ordeal in the short term, but all suffered permanent damage, and a number died prematurely.

The action failed in its immediate purpose – that of obtaining the release of the men involved – but it was a pyrrhic victory for His Majesty’s Government. It was no coincidence that it was during the months of the strike that IRA activity in the county increased dramatically, reaching levels that were more or less sustained for the remainder of the War of Independence – and it is impossible to suggest that the two phenomena were unrelated.

As we mark the centenary of the strike, the names of those who during these awful weeks challenged British rule in Ireland in one of its most secure citadels deserve to be remembered with pride and gratitude by the citizens of the Rebel, Premier and Treaty counties, and by their compatriots more generally.

– This article by Dr Gabriel Doherty was first published in the Irish Examiner on 2 January 2021 –