In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Civil War Politics: A Volatile Clash of Loyalties

1922 was characterised by the fight between practical politics and physical fighting that combusted into conflict, writes Dr Ciara Meehan

‘Famous leader killed in Dublin’ was how this newspaper reported the assassination of Seán Hales in December 1922. Steeped in the republican tradition, the Bandon native had been a battalion commander in Cork and head of a flying column during the War of Independence, leading various ambushes and attacks. Despite being considered an extremist, he supported the Treaty, which his brother Tom opposed.

The Cork TD had been at lunch with Pádraig Ó Máille, the Leas Ceann Comhairle, at the Ormonde Hotel on the quays in Dublin on 7 December. The two men were about to make the short drive to Leinster House when they were targeted by anti-Treaty gunmen. They were acting under Liam Lynch’s orders to shoot any member of parliament who had voted in favour of the Public Safety Act. Hales was killed and Ó Máille was seriously wounded. The Irish Free State was one day old. Democracy was under attack.

1922 was characterised by a struggle between practical politics and physical fighting, with the former seeking to win out over the latter as the way for ‘doing’ life in the new state. Legitimacy underpinned both, a theme that permeated political debate and propaganda, and which ultimately fuelled the Civil War.

The debate over the Treaty did not end with the ratification of the agreement by the Dáil on 7 January 1922. The anti-Treaty side moved quickly to disseminate their case before it was put to a public vote, launching a new newspaper, Poblacht na hÉireann: the Republic of Ireland. Early the following month, Cumann na mBan became the first republican organisation to reject the Treaty, when the majority of those present voted against it at a special convention. Éamon de Valera would go on to make a series of speeches around the country, for which he was accused of inciting violence.

The pro-Treaty side began printing its own newspaper, An Saorstát: the Free State, in February. The newspaper largely focused its efforts on explaining why the Treaty should not be repudiated, often making a case for why de Valera’s alternative, as outlined in his Document Number 2, was not workable, or alluding to the threat of a return to war with Britain.

As the prospect of civil war hung in the air, steps were taken to refocus energies on finding a way forward through politics instead. An electoral pact agreed by Michael Collins and Éamon de Valera offered voters panels of pro- and anti-Treaty candidates for the June 1922 general election with a view to creating a coalition government thereafter.

Both sides agreed to suspend their propaganda during this period, but signs of the divide still crept in. Though the articles printed in Free State were more muted than they had been, the newspaper repeatedly printed an advertisement for the Treaty fund that pointedly asked, ‘Where does your interest lie? In good government or in gun-law?’

The ‘pact’ failed, and the political complexion of the third Dáil was considerably different to that of its predecessor. The combination of proportional representation – the first time it was used in an Irish general election – and the presence of Labour and other interests, many of whom also supported the Treaty, thwarted Collins’ and de Valera’s efforts. Both sides of Sinn Féin had criticised the smaller parties during the campaign for being ‘self-interested’ and for not stepping aside. Intimidation occurred in parts of the country. Both had also argued that farming and labour interests were already catered for within Sinn Féin, thus negating the need for additional parties.

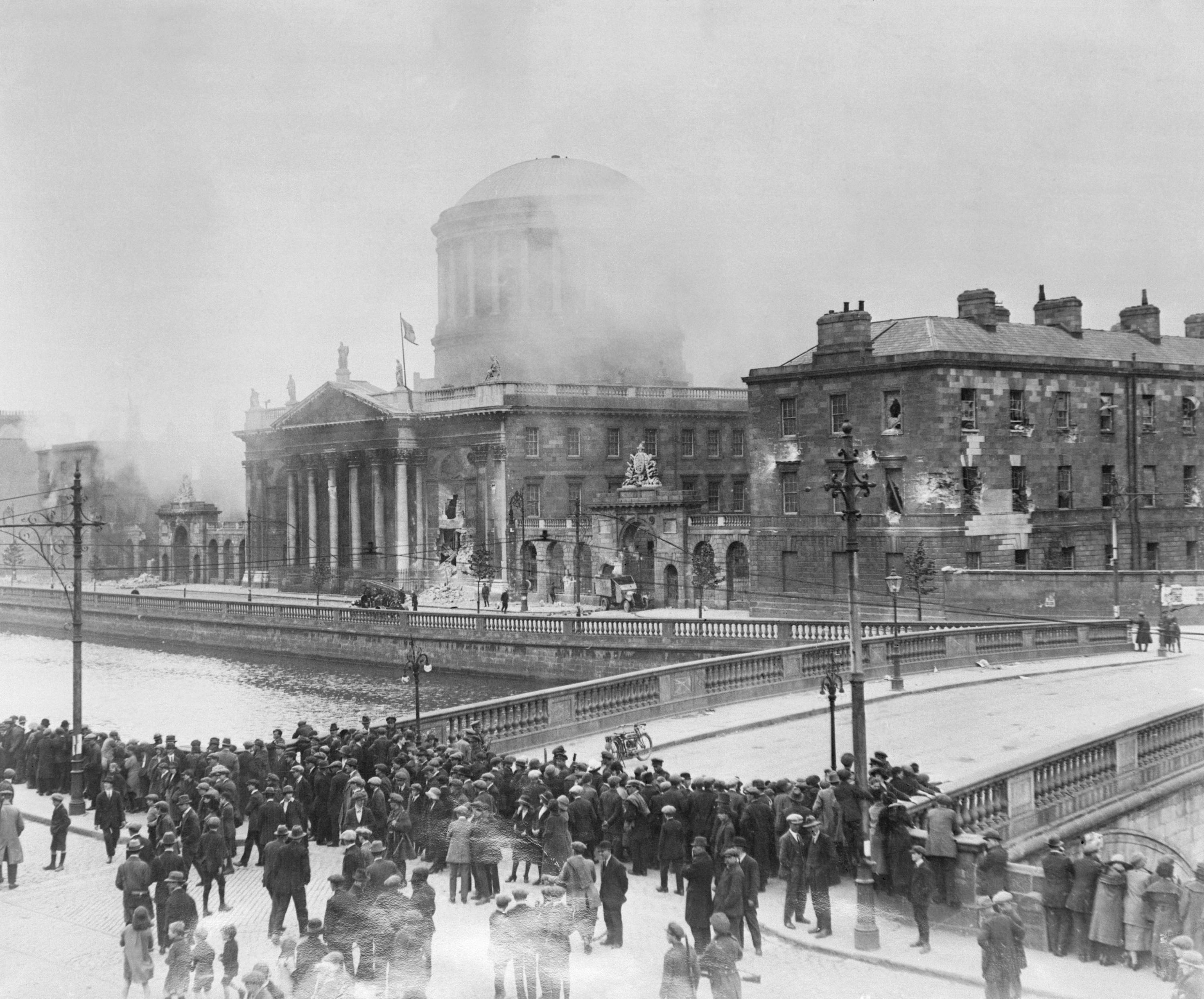

Less than a fortnight after the election, the National Army began shelling the Four Courts, which had been occupied by the anti-Treaty IRA since April. Taken as the official start of the Civil War, fighting overtook politics as the IRA and the National Army clashed in various parts of the country in the weeks and months after.

Repeatedly postponed because of the fighting, the first meeting of the Third Dáil finally happened on 9 September. Reporting on the occasion, the Irish Examiner noted in the same piece the ‘large sweeping operations’ underway in parts of the country by the National Army to squash the ongoing guerrilla war being waged by the IRA. Such articles serve as a reminder of the co-existence of practical politics and physical fighting in this period – that even at times when fighting, or the threat of it, seemed to eclipse all else, behind the scenes, for example, the new constitution was being drafted.

The Free State formally came into existence on 6 December 1922, exactly one year after the Treaty had been signed in London. The provisional government of the third Dáil became the executive council, and W.T. Cosgrave was re-elected President (the forerunner of the office of the Taoiseach).

Observing the meeting, a reporter for this newspaper wrote of the government’s intention to ‘persevere in its efforts for the advancement and development of the country’. But Cosgrave reserved a significant proportion of his first address to the Dáil to denounce those who sought to undermine the legitimacy of the new state. Moving quickly from expressing his pride in being the ‘first man called to preside over the first government’, he criticised the ‘mad efforts’ of those who opposed the Treaty. He lamented the loss of energy spent ‘trying to hold what we have won – not from those lately our enemies, but from those … who set their own narrowness … against the broad good sense of the people’.

But his criticism was heard only by like-minded politicians. The anti-Treaty side continued the policy of abstention that Sinn Féin had adopted for Westminster, and the opposition benches were sparsely occupied. Thomas Johnson, leader of the Labour Party and the opposition, made clear that his party had complied with the contentious oath only so that they could give ‘effect to the will of the organised workers’.

Cosgrave also mentioned the North in his speech, affirming that ‘our Northern policy … must be construed with respect to the Treaty’. At this time, of course, the belief still held that the Boundary Commission, provided for under the terms of the Treaty, would solve the problem of partition. Indeed, even some British politicians appeared to give credence to this in public, with David Lloyd George having earlier said that Ulster could be persuaded into being part of the Free State structure. Hopes would, of course, be later disappointed, but just as the promise of the commission explains the near absence of the North from the Treaty debates, so too does it explain its limited appearance in political debate at this time.

The killing of Seán Hales just one day after this meeting was noted at the outset of this article as a sign that democracy was under attack. But the risk did not come from those who opposed the Treaty alone. The government’s response had the potential to destabilise the democratic legitimacy of the new state in the eyes of observers.

Speaking in the Dáil, Cosgrave framed the attack as being part of a ‘diabolical conspiracy’ that needed to be squashed. In reprisal for Hales’ death and to send a strong message, four prominent anti-Treaty prisoners – Rory O’Connor, Liam Mellows, Joe McKelvey and Dick Barrett – were executed without trial. As these men were already in prison at the time of the shooting, the government had clearly stepped outside the rule of law.

Thomas Johnson accused the government of killing the new state at its birth. Democracy survived. Nonetheless, the vigorous way in which the government pursued the war, particularly the use of execution without trial, cast a long shadow.

By the time that Frank Aiken, then Chief of Staff of the IRA, ordered his forces to dump arms in May 1923, the country had largely settled down to the habit of practical politics. Although those TDs who opposed the Treaty still remained outside the Dáil, inside the parliament, the government was busy building the new state and scaffolding its development.

The statute books for the first years of independence record immense activity. Various image building projects – including membership of the League of Nations and the successful staging of the Tailteann Games – had also been undertaken to signal to international observers that the Free State was functioning, and that the Irish were capable of self-government.

The language of the Civil War was never far away, however. Not only did it frame much of the political propaganda throughout the 1920s, but it routinely re-surfaced in the decades that followed. As recently as the 2020 general election, commentators wondered if the Fianna Fáil-Fine Gael coalition finally signalled the end of Civil War politics.

Dr Ciara Meehan is author of The Cosgrave Party: a History of Cumann na nGaedheal

– This article was first published in the special Irish Examiner Supplement 'Civil War: The conflict that ripped the county apart', published 13 June 2022 –