In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

1921 Brought Challenges on Multiple Fronts

Ulster, the campaign for diplomatic recognition of the republic, and the papacy were all at play, writes Gabriel Doherty

After the Government of Ireland Act received royal ascent on 23 December 1920, the principal political initiative undertaken by the British Government during the Irish War of Independence moved from the realm of debate into that of implementation. For most of the remainder of the conflict the focus of Dublin Castle and Downing Street was on the growing military threat posed by the IRA. Political considerations were not completely ignored, however, as the British sought to undermine the stated position of the leadership of Dáil Éireann that they spoke and acted on behalf of an independent state.

Those republicans, of course, were themselves far from idle during the same period, as they sought to both resist such encroachments on their hard-won gains, and to further enhance the credibility of their claim, domestically and internationally, to have supplanted British rule.

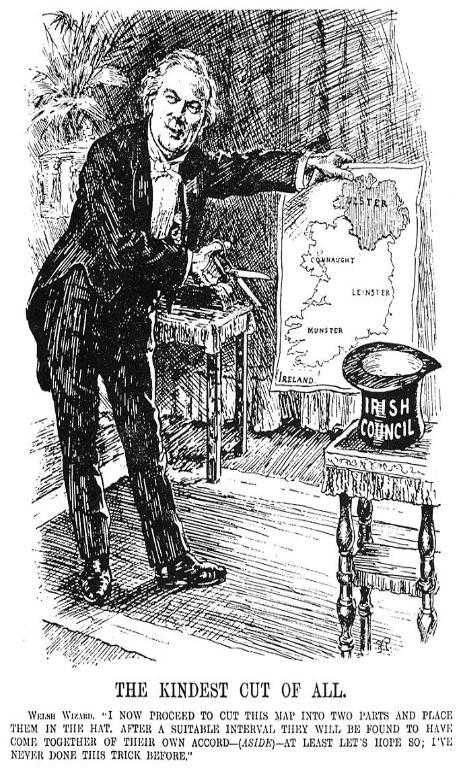

A cartoon from Punch in 1920, depicting British Prime Minister David Lloyd George’s plan to partition Ireland. © Granger Historical Picture Archive.

Quite distinct challenges faced the British Government on either side of the new border they had created. The simpler of the two, not surprisingly, came in the six counties. There was the organisation of a distinct civil service drawn primarily from the ranks of the existing staff of Dublin Castle; the drafting of orders in council to facilitate the holding of elections to the new parliament; and the obtaining of the co-operation of local unionist élites to ensure the smooth transition of political power to the new régime. The decision of Edward Carson to step down from his position as leader of the Ulster Unionist party in February 1921 was a fortunate development. It created an opportunity for the younger, organisationally-minded, and locally-based James Craig to become the first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland when the time came for his appointment four months later.

The south presented a very different story. Herbert Asquith criticised Lloyd George’s Irish policy as ‘giving to Ulster [or six counties of same] a Parliament which it did not want, and to the remaining three-quarters of Ireland a Parliament which it would not have,’ and this encapsulated the government’s dilemma. To fail to proceed with elections in the south at the same time and in the same manner as in the north risked exposing London to the charge that it was afraid of Irish democracy, but to allow them to proceed ran the risk of gifting the republicans another electoral landslide, and enhancing their claim to independence in the court of world opinion.

There were two additional considerations that weighed heavily in Downing Street. The first, in the event of the predicted Sinn Féin victory, was the planned extension of martial law across the whole of, and the application of Crown Colony government to, the twenty six counties – courses of action that would have presented Sinn Féin with additional propaganda coups on top of their anticipated electoral triumph. The second was the increasingly precarious position of the southern unionist population. They pushed for the earliest possible end to hostilities that they believed threatened their very existence, almost irrespective of what form any political settlement might take (though they were desperate to avoid partition as part of same). To put it mildly, the fortunes of the northern nationalist community did not weigh heavily on British government minds.

If the working out of the complications of the Government of Ireland Act was one political challenge in 1921, another was the simultaneous assault on, and defence of, the Republic, by Dublin Castle and Dáil Éireann respectively. Owing to the extreme pressure exerted by the former, the Dáil itself could only meet on four occasions between January and May 1921. With a number of TDs in prison at this point, more interned, and the remainder ‘on the run’, it took all the ingenuity (and courage) of its members to meet even on this limited number of occasions, and to sit as a symbolic gesture of defiance of the British Government.

The Dáil courts, and those local authorities (the vast majority) which had recognised the legitimacy of the Dáil and had repudiated British control, were the objects of particular attack by the forces of the Crown, primarily because they had been such outstanding republican successes stories the year before. The former were driven underground and the latter were both starved of the traditional grants from the Local Government Board (LGB) and saddled with the payment of collective fines to fund compensation payments to the victims of IRA attacks. And as at central level, many local councillors (and not just those elected under the Sinn Féin banner) found themselves imprisoned if not worse: the killings by Auxiliaries of the serving Sinn Féin Mayor of Limerick, George Clancy, and his predecessor Michael O’Callaghan, on 7 March 1921, stand out in this respect. Bearing these factors in mind, the IRA attack on the LGB central office in Dublin’s Customs House in May was more widely supported within the movement outside Dublin than is usually acknowledged.

The ‘Belfast boycott’ sponsored by the Dáil was vigorously enforced, and most certainly did damage to a number of smaller trading enterprises in the six counties – but at the cost of seeming to give point to the very partition of the island that the action was designed to forestall.

Two other examples of the activities undertaken by agents of the Dáil in the first half of 1921 deserve attention. The first was the on-going search for diplomatic recognition of the Irish Republic from foreign states, and the work of publicising the achievements of the Dáil abroad. The focal point of these activities had been the United States, but the clear victory of Warren Harding in the presidential election of November 1920, and the absence of any prior commitment on his part regarding the Irish Question, meant there was little more that could be done on this front – whence de Valera’s return to Ireland at Christmas 1920.

Given the extent of British power at this juncture, it was inconceivable that any established state would even contemplate granting the recognition sought by Irish republicans, and the belief that they might was a sign of just how little those republicans appreciated the role that realpolitik played in statecraft. Even the new, radical states, such as the Soviet Union, that had come into being in the teeth of British opposition during the revolutionary turmoil induced by the First World War, ultimately found it in their interests to curry favour with London, and brought their dalliances with Irish republican representatives to a conclusive halt.

There was one exception to this general trend, and it involved a state that was far older than any of those involved (or not) in the recent war, and who, by its unique nature, was an object of fascination, indeed adoration, in Ireland – the Vatican. Itself in a form of diplomatic purdah at this time (a state of affairs that lasted until the Lateran Treaty of 1929), the British were, nevertheless, acutely conscious of the prestige enjoyed by the Papacy in Ireland, and expended much effort in extracting a condemnation of republican violence from the Holy See. There were powerful elements within the Vatican’s diplomatic bureau that were reportedly sympathetic to such a course of action, but Pope Benedict XV was aware of the overtures and refused to bestow his imprimatur on them. His Apostolic Letter to Cardinal Logue of 27 April 1921, which was read at all masses in the country four weeks later, officially declared that the universal church was neutral in the contest, but its condemnation of the arson then widespread across the country, and the attacks on both church property and personnel (notably the slayings of clergy), was inevitably interpreted as being directed primarily against the British side.

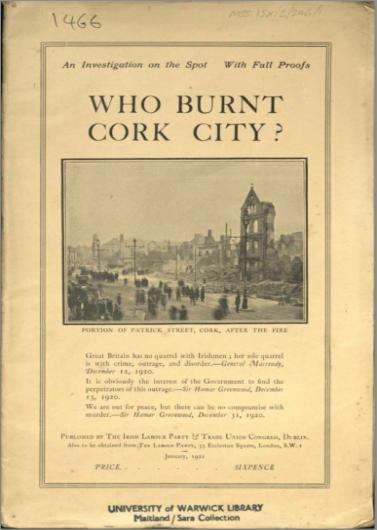

Publicity was the other arena in which the Dáil sought to maintain the strong profile it had achieved during 1920. The British policy of official reprisals, inaugurated in January 1921, was a boon to the republicans in this respect, for it was precisely the type of ‘Hunnish’ tactic so strenuously condemned by the British themselves when used by the Germans in the Great War. Other developments similarly played into the hands of the separatists. These included the declaration (sought by the British military themselves) by a British court that a state of war existed in Ireland, the humanitarian work of the American Relief Committee and the White Cross Society, the conclusions (highly sympathetic to the Irish nationalist viewpoint) arrived at by the American Commission on the War in Ireland, and other anti-British publications such as the Irish Labour party’s pamphlet Who burned Cork city? All were grist to the editorial mill of the Dáil’s Irish Bulletin, which maintained not alone its daily publication schedule (notwithstanding the logistical difficulties in doing so) but also its position as a source of reliable (if inevitably skewed) information on Irish affairs amongst British and foreign journalists.

Publicity was the other arena in which the Dáil sought to maintain the strong profile it had achieved during 1920. The British policy of official reprisals, inaugurated in January 1921, was a boon to the republicans in this respect, for it was precisely the type of ‘Hunnish’ tactic so strenuously condemned by the British themselves when used by the Germans in the Great War. Other developments similarly played into the hands of the separatists. These included the declaration (sought by the British military themselves) by a British court that a state of war existed in Ireland, the humanitarian work of the American Relief Committee and the White Cross Society, the conclusions (highly sympathetic to the Irish nationalist viewpoint) arrived at by the American Commission on the War in Ireland, and other anti-British publications such as the Irish Labour party’s pamphlet Who burned Cork city? All were grist to the editorial mill of the Dáil’s Irish Bulletin, which maintained not alone its daily publication schedule (notwithstanding the logistical difficulties in doing so) but also its position as a source of reliable (if inevitably skewed) information on Irish affairs amongst British and foreign journalists.

The political considerations that led the British government to make an offer of qualified dominion status to the republican leadership immediately following the Truce of July 1921 lie outside the remit of this article. But the mere fact that the British abandoned, almost overnight, their ‘murder gang’ rhetoric in favour of a recognition that such figures, and the movement they directed, possessed an overwhelming democratic mandate was a huge morale boost to those involved, after a hellish winter and spring. What, if any, new political alignments would develop as a result of these engagements in the second half of 1921 only time would tell.

This article was first published in the Irish Examiner on 21 March 2021