In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Over 600 rebels mobilised in the western county, but, with no arms nor reinforcements arriving, they had no choice but to reject the urgings of their leader Liam Mellows and disband, writes Conor McNamara

Galway was one of the few places outside of Dublin to have a significant Volunteer mobilisation at Easter 1916. Over 600 Volunteers under the com- mand of Liam Mellows traversed south-east Gal- way for five days, attacking the police at Clarinbridge, Athenry, Oranmore, Carnmore, and Lydecan.

One police constable was killed and several taken captive by the insurgents. The group commandeered foodstuffs, cars, horses, and cattle, destroyed railway lines, barricaded roads, and generally defied the police authorities over a large section of Galway countryside.

The charismatic Mellows was very much an outsider in the county, but a figure who attracted great loyalty among his followers.

The plan for the Rising in Galway was predicated on the successful delivery to the county of 3,000 rifles from the Aud. When the arms landing in Kerry failed, the prospects for a concerted and meaningful rural dimension to the Rising ended. The 600 or so men who went out in Galway were armed with fewer than 30 .303 service rifles, a few miniature rifles, and 300 shotguns.

The plan for the county envisaged two distinct phases: Companies were to be armed at central points, before returning to their districts to attack police barracks, then proceed as a combined force into heavily-garrisoned Galway.

A few months before the Rising, Patrick Pearse visited Athenry and asked if the local Volunteers, “could hold a line to the river Suck in Ballinasloe” in the event of a rebellion. He was told that, because of their poor equipment and armament, their only chance was to attack local Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks.

The first shots of the east Galway Rising were fired just after 7am on Easter Tuesday, when 100 men from Killeeneen and Clarinbridge attacked the police barracks in the village of Clarinbridge.

The parish priest, Fr Tully, who was saying Mass when the attack began, pleaded with Mellows to call off his men. He refused and called for the barracks to surrender.

After hours of fruitless sniping, a small force was left to keep the building under intermittent fire while the main body of Volunteers marched seven miles to nearby Oranmore, taking with them three RIC men who had been caught unawares while on patrol.

As the rebels approached the village of Oranmore, they were joined by the Oranmore and Maree companies. The four constables on duty in the village barricaded themselves into their barracks. Thirty-five rebels tried to rush the door but were greeted with a fusillade from the rein- forced windows above.

When a contingent of Connaught Rangers arrived by special train from Galway to relieve the beleaguered police, a prolonged firefight ensued as police and army charged down the main street. Mellows decided to move west to the Athenry agricultural college, cutting telegraph wires, tearing up railway tracks and commandeering foodstuffs as they went. The rebels were joined in the town of Athenry by Volunteer companies from the nearby districts of Athenry, Kilconieron, Coldwood, Coshla, Rockfield, Derrydonnell, and Newcastle.

As the rebels regrouped at their new camp, they heard the distant boom from the big guns of the Naval cruiser, The Gloucester, in Galway Bay. The indis- criminate shelling of the coast between Oranmore and Castlegar continued all week, and the effect on the atmosphere in the rebel camp and the countryside was immense. Some Volun- teers believed their German allies had arrived and that the booming represented a naval battle between U- boats and the British navy.

WHILE hundreds of Volunteers massed at At- henry on Tues- day night, the Claregalway and Castlegar companies billeted for the night in the small village of Carnmore, six miles east of Galway town, to await orders from Mellows. A group of Special Constables and RIC formed a convoy in Galway town and drove to Carnmore to confront the Rebels.

Volunteer leader Mick Newell later recalled: “The enemy advanced up to the crossroads and Constable Whelan was pushed by District Inspector Heard up to the wall which was about four feet high, the District Inspector standing behind [Patrick] Whelan and holding him by the collar of his tunic.

Old IRA comrades at Killeeneen, where the Volunteers mobilised in 1916.

“Constable Whelan shouted, ‘surrender boys, I know ye all’. Whelan was shot dead and the District Inspector fell also and lay motionless on the ground. They got back into the cars and went in the direction of Oranmore.”

Following the killing of Constable Whelan, the insurgents marched to Athenry, joining up with their comrades. On Wednesday evening, over 650 rebels awaited arms and reinforcements, but none were to arrive and the group was placed in an increasingly invidious position: As each day passed the military were gaining the upper hand in Dublin and well armed military reinforcements would soon depart from the capital to destroy the Galway Volunteers.

They had become, to all intents and purposes, sitting ducks. The initial euphoria faded as the realisation sank in that it was only a matter of time before the group must face better-equipped British troops. Their chances of mounting an effective defence were small, and demoralising rumours swept the camp of the imminent arrival from Dublin of troops armed to the teeth.

Moyode Castle, Athenry, which was occupied by the Galway rebels.

As night fell, Mellows decided to march south towards the Burren to join up with the Clare Volunteers. Late on Thursday night, the group marched south to Limepark, a ruined big house near Peterswell, on the Galway-Clare border. Fr Henry Feeney, who had been with the Volunteers all week, was joined by Fr Thomas Fahy of Maynooth College and the pair pleaded with Mellows to disband his men before the military decimated them. The resolute Mellows refused.

Fr Fahy persuaded him to allow the case to be put to a meeting of brigade officers, however, and Volunteer Michael Kelly recalled:

“A discussion then arose mainly between the priest and Mellows. The priest was trying to convince the meeting that, as the Volunteers in Dublin had surrendered, the Galway

Volunteers should disperse, as the position was hopeless in the circumstances.”

Mellows, as commanding officer, addressed his men: He would not order them to disband, but he was willing to let them decide their own fate. Only Mellows and his deputy Ó Monacháin voted not to disband.

Following the Rising, 328 men from Co Galway were arrested and deported to jails across Scotland and England, before joining their comrades in Frongoch.

In letter to a friend in 1919, Mellows wrote of the Galway men he commanded: “It will never be, in our day anyway, in all probability, but it is to them the thanks of future generations of the Irish people will be due. They gave all in silence, seeking no reward and getting none.”

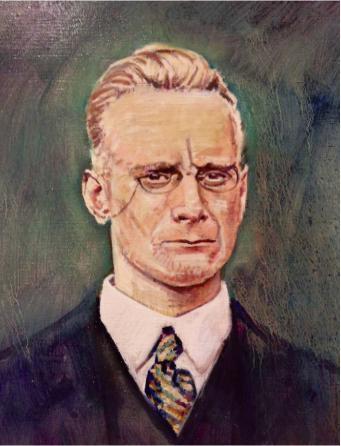

Liam Mellows: Republican Enigma

LIAM Mellows, who led the Galway Rebels during Easter Week, was shot dead by the Irish Free State on December 8, 1922.

It was one of the first brutal executions of Anti- Treaty IRA Volunteers by the National Army during the Civil War. He was 30 years of age and had given his entire adult life to the cause of an Irish Republic.

William ‘Liam’ Mellows was born in 1892 in Lancashire, England. His father was a military officer and Liam and his brother Herbert, known as Barney, moved to Wexford in their childhood.

Inspired by their love of Irish history, the brothers became indefatigable organisers for Na Fianna Éireann boy scouts and the Irish Volunteers, formed in 1909 and 1913, respectively.

Of small stature, but physically fit, a non- drinker or smoker, Mel- lows’ sole relief from his life’s work of building an Irish Republic was playing his beloved fiddle for friends and comrades. Sent by HQ to organise the Galway Volunteers in March 1915, Mellows’ personal steel was cloaked by his inoffensive character.

Volunteer Frank Hynes recalled: “My impression of him was that he may be a clever lad — he was about 22 years — but couldn’t be much good at fighting... I learned later that he was determined to give his life in the fight.”

Following the Rising, Mellows escaped to the United States where he spent several unhappy years in New York involved in various capacities with Clan na nGael and other branches of the republican movement.

A close friend of Volunteer leader, Patrick McCartan, he was incarcerated in The Tombs Prison in late 1917 for entering the US without a passport.

While abroad he was elected Sinn Féin MP for both Galway East and Meath North in the December 1918 general election. On his return to Ireland in October 1920, he was appointed director of arms purchases at IRA HQ.

He implacably opposed the Anglo-Irish Treaty and was part of the Anti-Treaty IRA leadership that occupied the Four Courts in April 1922. Captured in the attack on the complex by the National Army, he was subsequently shot dead in December 1922, in reprisal for an attack by the Anti-Treaty IRA in which Cork TD Sean Hales was killed.

Mellows’ career is a classic example of the disenchantment among a coterie of republican leaders with the Irish revolution’s political direction. Like Patrick Pearse, he shared English ancestry, but had a pro- found sense of the republican cause’s righteousness, and could not countenance any form of political compromise.

Like Pearse, he held a close bond with his only intimate friend, his brother. Both were devoted to their mothers, with whom they shared their ideals for their country.

In a letter to an acquaintance in 1919 Mellows wrote with typical lack of ego:

“You place me on too high a pedestal. Someday you may turn iconoclast and then you will find that, like all idols, this one has feet of clay... And after all talk is cheap. It is the deed that counts, and there I have failed lamentably...There are men and women in Ireland today, compared with whom I am as nothing, simple, honest, knowing nothing of the maze of politics or the ways of the great world, yet, they cherished in their hearts great ideals and noble aspirations... Dreamers fanatics, intransigents, fools, yes, but unconquerable and sublime.”

■ Dr Conor McNamara is NUI Galway 1916 Scholar in Residence. His books include The Easter Rebellion 1916: A New Illustrated History (Collins Press, 2015). This article first appeared in ‘The Rising in the Regions’ supplement, published by the Irish Examiner on 21 March 2016