In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

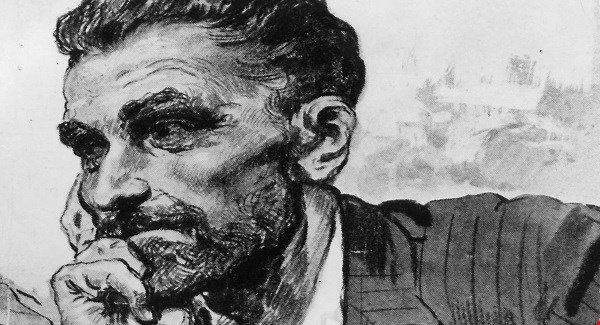

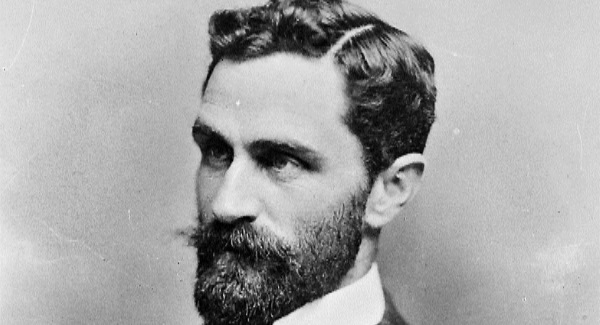

Roger Casement: Complex Soul Defies Monochrome Portrait

On the centenary of Roger Casement’s death, Ryle Dwyer examines the background to his execution for trying to get German help for the Easter Rising that he later tried to call off.

Roger Casement was hanged at Pentonville Prison in England for high treason on this day 100 years ago. Though remembered as a patriot in this country, mystery and controversy still surround his execution.

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War. he travelled to Berlin to enlist German help for the forthcoming Irish rebellion. In much of the English-speaking world, especially in the US, the Germans were pilloried for their attack on tiny Belgium but, having been knighted for exposing the savage conditions of slavery in the Belgian Congo, Casement took a different view of the attack on Belgium.

“There may be in this awful lesson to the Belgian people — a repayment,” he wrote. What the Germans were doing in Belgium did not compare with the sufferings Casement witnessed the Belgians inflict on the natives of the Congo.

“Germany is fighting the battle of European civilisation at its best against European civilisation at its worst,” Casement wrote after the war broke out. He considered the British Empire “a monstrosity”.

The Germans authorised Casement to recruit an Irish brigade from among the 2,200 Irish taken prisoner while serving in the British Army, but he only managed to recruit 54 men, and he considered them the dregs of Irish society.

“The more I see of these alleged Irishmen — the less I think of them as being Irish,” he wrote. “They are the black blot of our claim to nationality.

“I used to be proud to be Irish,” he added, but now had reservations. “I feel ashamed to belong to so contemptible a race.”

He also developed misgivings about the Germans.

“The more I see of the ‘governing classes’ in Germany, the less highly I estimate their intelligence,” he wrote the following day. He asked the Germans for 100,000 guns but they were only willing to provide 10 machine guns and 20,000 captured Russian rifles, which Casement dismissed as “a paltry gift of second- hand rifles”. The Germans were supposed to deliver him in a submarine to the arms ship, the Aud, in Tralee Bay, where he was to direct the landing of the guns, but he had different plans.

He was hoping to stop the Rising because he realised it would be a disaster.

“If I can only get ashore a little head of the rifles I may be able to stop the ‘rising’.

“I tread the pavement with joy — my last day in Berlin, city of dreadful night and most ‘forbidding society’,” he noted in his diary on April 10, 1916. “How I loathe the place!”

Indeed, Casement had come to think of Germany as his prison.

He was arrested within hours of landing at Banna Strand in Co Kerry on Good Friday. That evening, he asked Fr Francis Ryan, a Dominican priest who called on him at the police station in Tralee, to pass on a message to the Republicans to call off the Rising, but the priest procrastinated over the weekend and only passed on the message on Easter Monday morning.

By then, Casement had been moved to London, where he was questioned on Easter Sunday by Basil Thompson, head of the Criminal Investigative Division at Scotland Yard, and Admiral William ‘Blinker’ Hall, head of Naval Intelligence.

Casement pleaded to be allowed to appeal to those in Dublin to call off the Rising, but Hall wished for it to go ahead so that Irish nationalism could then be suppressed. “It is better that a cankering sore like this should be cut out,” Hall insisted.

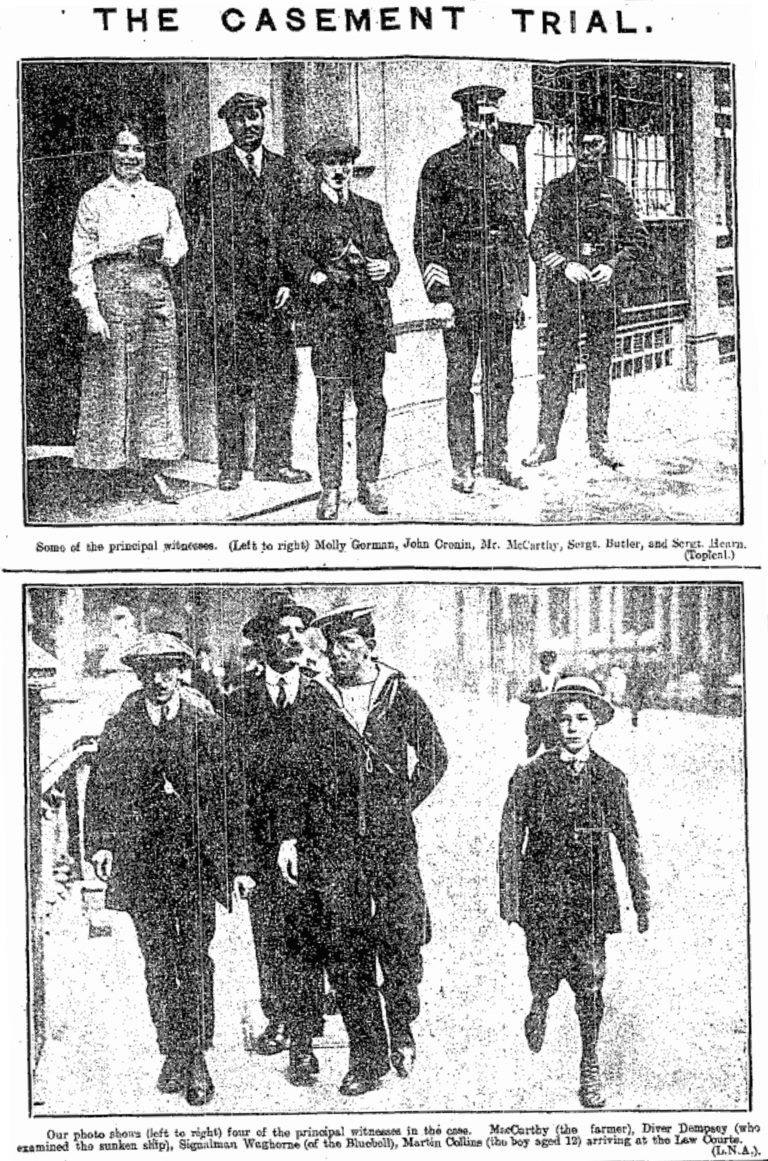

In effect, Hall facilitated the rebellion while Casement went on trial in London for high treason on June 26, 1916. There was conclusive evidence that he had tried to recruit Irish prisoners-of-war in Germany to fight against the British in Ireland. His defence counsel, Sergeant Alexander M Sullivan, tried to defend the charge on strictly legal grounds, contending that the 1351 statue he was accused of violating did not apply to acts committed outside the United Kingdom. The prosecution told the defence it had got hold of a Casement diary with some salacious material indicating he had engaged in homosexual practices. It seemed the prosecution was hoping the defence would use the material to support a plea of insanity, but Sullivan rejected the idea.

“I did not even discuss it with Casement,” he wrote, “beyond assuring him that the diary would not be alluded to during his trial. He was very nervous about it.”

It was possibly because of the danger of being cross-examined in relation to the diary that Casement decided not testify in his own defence but he was allowed to deliver an unsworn address to the jury on the third day of his trial. In this, he denied ever asking any Irishman to fight for Germany, or that he had ever received foreign money.

“I must state categorically that the rebellion was not made in Germany, and that not one penny of German gold went to finance it.”

After just 55 minutes of deliberation at the end of the four-day trial, the jury convicted Casement, and he was duly sentenced to death. He appealed, but this was dismissed on July 19 after a two-day hearing.

There were strong calls for clemency. Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, drew up a petition that was signed by 39 prominent people including writers Arnold Bennett, G K Chesterton, John Galsworthy, and Jerome K Jerome. W B Yeats and George Bernard Shaw also spoke out on Casement’s behalf.

Strong sympathy was roused in the US, where William Randolph Hearst threw the support of his newspaper chain behind a US Senate resolution calling for Casement’s reprieve. The resolution was duly passed but, due to a mix-up, was not delivered until an hour after his execution.

British officials had deliberately undermined the clemency campaign by leaking extracts from Casement’s diaries to prominent political and religious figures, as well as selected reporters. Photographs of the diary extracts were also circulated with the aim of undermining sympathy for him by depicting him as a moral degenerate.

British ambassador Cecil Spring Rice warned Monsignor Giovanni Bonzano, the Papal representative in Washington, that “His Majesty’s Government were in possession of evidence which would make it extremely undesirable that priests of the Catholic Church should publicly ascribe to Casement the character of a Christian martyr whose life should be held up as a model to the faith”.

The ambassador also gave “a similar hint” to Cardinal John M Farley of New York. The warning was supposedly to save “high officials of the Church” from embarrassment.

On the eve of Casement’s execution, Walter H Page, the US ambassador in London, told British prime minister Herbert Asquith he had seen extracts from Casement’s diary.

“Excellent,” Asquith replied, “and you need not be particular about keeping it to yourself.”

The diary issue was really an irrelevant distraction. Instead of focusing on his brave attempt to stop the rebellion and the injustice of his execution, his supporters became obsessed with futile efforts to depict Casement’s authentic diaries as forgeries.

This article was first published in the Irish Examiner on 3 August 2016