In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

How the Cork Labour movement defined the struggle for Irish independence

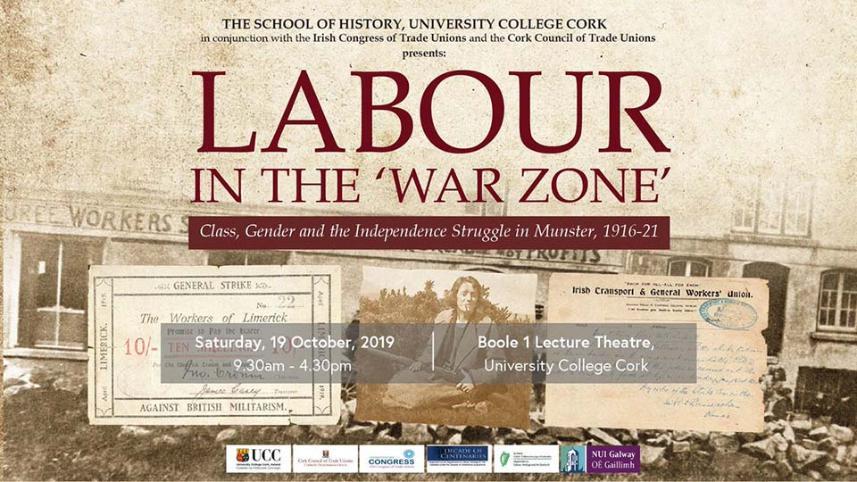

A major one-day conference on the Labour movement and the struggle for independence takes place in University College Cork on Saturday. Here looks at the labour movement in Cork.

A major one-day conference on the Labour movement and the struggle for independence takes place in University College Cork on Saturday.

The conference, which is open to the public, will feature leading historians discussing often neglected issues such as strikes, occupations, the role of women as combatants and the class tensions that permeated the period. Here looks at the labour movement in Cork.

Until 1916, the Labour movement in Cork had, like all elements of local society, supported constitutional nationalism.

In 1909, the Home Rule party split when Cork MP William O’Brien broke away and formed the All-for-Ireland League, which quickly became the primary vehicle for constitutional nationalism in Cork. The split was reflected in the city’s Labour movement. After 1909, it had two trades councils: The Cork United Trades and Labour Council backed the O’Brienites and Cork District Trades Council backed the Redmondites.

But the Easter Rising initiated a political realignment towards Sinn Féin. On May 11, 1916, the District Trades Council appealed for clemency ‘to those concerned in the tragic and deplorable events of Easter week’ and strongly condemned the execution of its leaders. Both councils amalgamated in late 1916.

The new Cork Trades Council embraced the new political consensus more than most elements of Cork society.

Cork Labour’s biggest and most efficacious protest during this period was not about wages or conditions. Rather, it was its implementation of the Irish Trade Union Congress’s one-day general strike on April 23, 1918 to oppose the imposition of conscription in Ireland.

As John Borgonovo put it, ‘Cork’s trade unions moved into the vanguard . . shops and factories closed, trains and trams were idle, pubs shut their doors, and the harbour fell silent.’ About 30,000 attended what was the largest protest in Cork’s history.

The trades council and the 1918 general election The conscription crisis had further reinforced the growing Labour-republican alliance in Cork. On October 10, 1918, tragedy had struck the Cork Trades Council when its president Patrick Lynch went down with the HMS Leinster.

His death opened the way for Éamonn O’Mahony, a republican, to become council president. The council’s All-for-Ireland League- orientated leadership, whom Labour-republicans disparagingly called the ‘old gang’, was dealt a heavy blow by Lynch’s death.

The historic 1918 general election illuminates the extent to which republicanism had come to permeate the council. Its rank-and-file opposed a Labour Party candidate entering the race. Liam de Róiste, Sinn Fein candidate for the Cork City constituency, observed that there was little class consciousness among workers and that most would vote for Sinn Féin over Labour. O’Mahony told him that ‘everyone as far as I can judge . . . is against a fight between Labour and Sinn Féin’.

De Róiste agreed, predicting that the council would split if a Labour candidate was put forward.

Trade-union leaders spoke at 15 of the 18 Sinn Féin election meetings. At one such rally, John Good, the trades council’s republican secretary, proclaimed that ‘Labour and Sinn Féin were one and the same thing’ and that only a Sinn Féin victory could deliver the coveted ‘workers’ republic.’ De Róiste, in the most Bolshevik of rhetoric, told the crowd that ‘the day had come when the working classes would have power in the government of the country.’

No trade unionist spoke at any Home Rule party rally or played any role in its campaign.

The outbreak of the war of independence in January 1919 turned working-class attention to the national struggle as never before. As the war intensified across Ireland, the British government the Motor Permits Order, a decree stipulating that from November 29, 1919 motor vehicles could only be utilised with a permit.

The order was designed to assist the authorities to monitor private transport, through which arms were being carried. Motor drivers were outraged and immediately went on strike. They received unequivocal support from the trades council. In early 1920, however, the strike began to dissipate and on February 8 it was called off

Labour’s opposition to the order deepened its commitment to national independence.

The republicanisation of Cork Labour reached new heights during the municipal elections of January 15, 1920. The British government had introduced proportional representation to Ireland to undermine republican electoral success. In Cork, the ITGWU ran on a joint ticket with Sinn Féin.

The coalition won 30 seats out of a possible 49, giving it a four-seat majority. The trades council ran 12 candidates in five districts for the Labour Party, three of whom were elected. There was little that was new in the council’s manifesto.

It promised medical treatment for children, provisional of school meals, scholarships, direct labour on public works and trade-union rates for Corporation employees. De Róiste believed that ‘Labour, official or otherwise, has done very badly. These elections clearly show that the appeal to a war between classes is not a very moving one in Ireland.’

But the results contradict this assertion. Nationally, the Labour Party had its best municipal election and returned 324 candidates. Sinn Féin returned 422, compared to 213 nationalists and 297 Unionists. Labour secured one-quarter of the vote, second only to Sinn Féin, which secured one-third of it. Craft union conservatism lingered in Cork.

The ITGWU had wanted the trades council’s nominees to take a republican pledge, much to the annoyance of the Typographical Association which refused to fund the campaigns of such candidates.

The next great show of Labour support for the republic emanated from the new Sinn Féin- ITGWU Corporation. On March 21, 1920, at a special meeting to condemn the murder of Lord Mayor Tomás Mac Curtain by the Royal Irish Constabulary, the trades council passed the following resolution:

That we, the Cork and District Trades and Labour Council, representing the organised workers of Cork, place on record our abhorrence of the dastardly murder by the enemies of Ireland of revered Lord Mayor, Alderman Tomás MacCurtain; and that we tender to Mrs Mac Curtain, family and relatives our sincerest sympathies, and that we call on all workers, wherever possible, to cease work to-morrow to pay a tribute of respect to the memory of the late Republican Lord Mayor of this city, whom all Ireland to-day mourns.

The general strike was duly observed. The council had acted on its own initiative in a localised action not called by Congress. Although Cork Labour had long supported nationalist political causes, this strike was its first independent act of direct solidarity with the republicans.

Across Ireland, the most significant industrial actions all had strong republican dimensions; gone were the days when Labour’s sole expression of republicanism was its participation in the annual Manchester Martyrs commemoration.

It is indicative of Irish Labour’s political transformation that its biggest protest of the era was another political action: the general strike called by the ITUC on April 13, 1920 for the release of republican hunger-strikers at Mountjoy Prison and Wormwood Scrubs. The strike, which lasted for two days, was a resounding success. Like April 1918, Cork was brought to an industrial and commercial standstill. As the Cork Examiner reported, ‘not a shop is open. The trams are off the street . . . Even the hackney cars are off the stands. Railway termini are closed.

Ships at the quayside are there untouched . . . all schools are on ‘holiday’. Solicitors’ offices are also closed and the business of the Cork Quarter Sessions Court had to be adjourned for the day.’

De Róiste noted that ‘the stoppage was even more complete than during the anti-Conscription crisis . . . the postal officials also ceased work.’

A mass meeting of workers under trades council supervision was held at the City Hall where its president George Nason promised labour’s utmost support for the republicans.

Though not as comprehensive as the April 1920 strike, the era’s most momentous Labour endeavour was another political action: the embargo on the transportation of military forces and munitions by Irish railwaymen and dockers. It began at Dublin’s North Wall on 24 May 1920.

Two days later, Cork railwaymen resolved to bring the embargo Leeside. On June 5, the city’s dockers joined the embargo on when they refused to unload barbed wire from a ship and to raise Brian Boru drawbridge to allow it to pass. The military unloaded munitions ships over the coming weeks.

Nationally, the embargo lasted until 21 December and crippled the British government’s attempts to counter the IRA insurgency. The Cork Trades Council championed the strike and raised funds for the 1,200 victimised railwaymen. It sent about £300-400 a week to Dublin to sustain the battle.

In July, the council accused the Amalgamated Society of Engineers (a British union) of blacklegging and undermining the struggle when its members at Victoria (now Collins) Barracks continued to repair military vehicles.

By now, Labour had no qualms about acting as a republican auxiliary body. The growth of republicanism among workers meant that notions of class consciousness, trade union agitation, political independence and anti-militarism all became deeply intertwined.

Cork Labour increasingly viewed its struggle as a matter of politics rather than industrial relations.

The political environment continued to intensify the trades council’s republicanism.

Throughout the latter months of 1920, the MacSwiney affair dominated its discourse. On August 12, MacSwiney was arrested in a military raid on City Hall. He was jailed in Brixton Prison where he immediately went on hunger strike. On 19 August, the CTC issued the following declaration:

That we, the members of the Cork and District Trade and Labour Council, condemn in the strongest possible manner the inhuman treatment meted out to our Lord Mayor and other political prisoners at present confined in English and Irish goals; that we further condemn the action of the Government in deporting these prisoners to England as most inhuman and barbarous, seeing that they had been already several days without food, and were as a consequence unable even to stand, and we hereby pledge, on behalf of Labour here, our fullest support in bringing about their release.

Five days later, it conducted a one-hour strike in support of MacSwiney and the republican hunger strikers imprisoned in Cork gaol. On September 22, the CTC called another hour-long stoppage to facilitate workers attending a special mass for MacSwiney.

The council subsequently adjourned for the duration of the hunger strike to protest his treatment. On October 15, a third mass stoppage took place to allow workers to attend another mass in the lord mayor’s honour. By then, the patience of some employers was running thin.

Though Ford’s had warned that any walkout without permission would result in dismissal, its employees were undeterred. Edward Grace, the plant’s manager, shut down the factory until he could replace those who went out. Intervention from J.J. Walsh TD spared these workers – whose actions were praised by Deputy Lord Mayor Donal O’Callaghan – their jobs. MacSwiney died in Brixton Prison on October 25 after 74 days on hunger strike.

The next day, the CTC held a special meeting and unanimously declared:

That we, the members of the Cork and District Trade and Labour Council, extend to the Lady Mayoress, the brothers and sisters of the late Lord Mayor, his colleagues of the Corporation and his comrades of the Irish Volunteers, our deepest sympathy in the loss they have sustained; that we emphatically condemn the tyranny which has caused his untimely end in 6 foreign dungeon, and we call upon the workers of Cork to hold themselves in readiness for any call that may be issued to register this sympathy and show their appreciation of his great sacrifice for land and liberty.

The trades council ordered its members to cease work on October 29 as a tribute to MacSwiney. A few days later, representatives from the trades council and affiliated unions attended his funeral.

The trades council’s actions during the MacSwiney affair reinforced in working-class consciousness the commonality of interests between Labour and republicanism.

This strongly militated against the formation of an independent Labour identity in the public sphere.

The council discussed few of the numerous industrial disputes at this time. Instead, it regularly adjourned to protest the British government. Labour’s preoccupation with the country’s political situation meant it was poorly prepared for the coming employers’ offensive. In late 1920, the post-war economic boom came to a sudden halt and the economy was flung into a deep recession.

Employers set out to slash wages to compensate for a collapse in prices and demand. Workers would now face a more intimately known enemy closer to home.

This time, however, the Cork Trades Council had little to say the matter.