In This Section

- Home

- About Us

- Study with Us

- FMT Doctoral Studies

- Research

- CARPE

- Collaborations

- EDI

- People

- Film

- Music

- Theatre

Blog. Interview with Filmmaker Brendan Byrne.

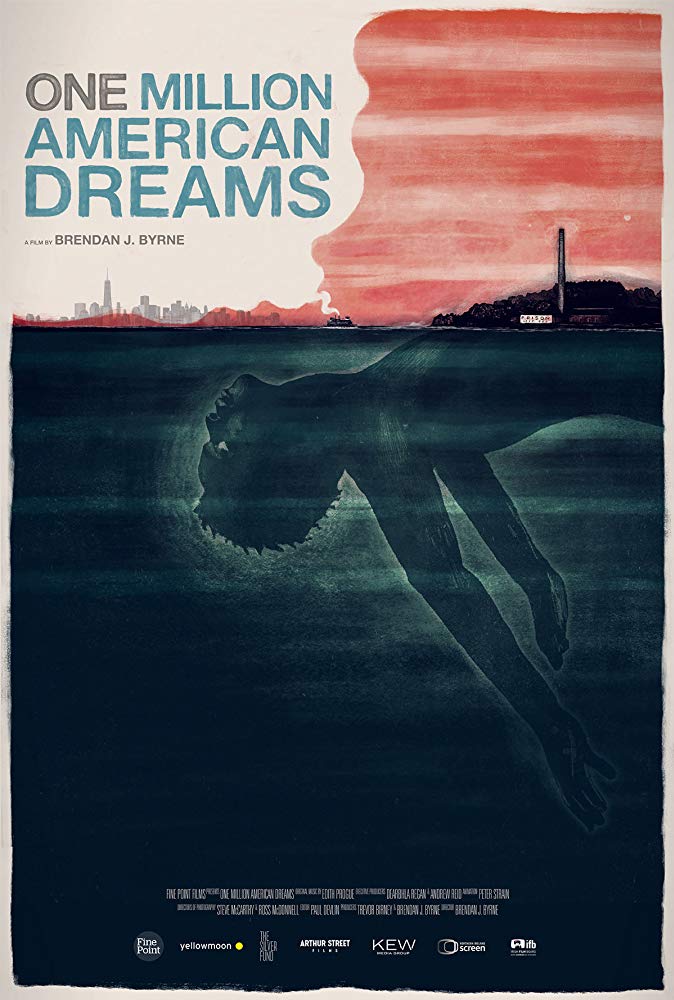

On November 17th, I saw One Million American Dreams as part of the Cork Film Festival...

This documentary explores the devastating hidden history of Hart Island, a mass grave site located in the Long Island Sound. After the screening, I had the opportunity to interview the director, Brendan Byrne. Byrne is an award-winning filmmaker who has made documentaries for RTE, BBC, and C4 for over 20 years. His documentaries and narrative films alike have been selected at the Toronto International Film Festival, the Cork International Film Festival, the Hotdocs festival, and others.

Gabrielle Ulubay: “Thank you for speaking with me today. I truly enjoyed One Million American Dreams and, being from the New York area, I found that it resonated with me in much of its commentary on the mythology surrounding America.”

Brendan Byrne: “I’m glad, thank you.”

GU: “It would be great to start by talking about your experiences in coming to make the film. In your Q&A, you called it ‘a difficult love letter to New York City,’ and it would be great for you to discuss how your relationship with New York has evolved to a point where you felt it was necessary to make this film.”

BB: “Well, I went to New York for the first time when I was seventeen years of age. I was about to go into my final year of school, and rarely does any schoolboy go to New York in the summertime that early--it’s usually the following year. But I had this opportunity to go, so I went, and never ever will I forget the moment when I arrived in JFK Airport. I took the bus--I was a student, so I obviously had very little money--so I took public transport from JFK down to Port Authority, and that bus journey is seared in my imagination to this day. I can see the people who were on the bus. I can remember vividly what I saw in the window: I saw a guy with a black t-shirt and a guitar case on the bus, and I was so excited to arrive in this city after having seen the movies and everything, that I actually thought he was Bruce Springsteen. I saw kids playing basketball in Queens, and the bus circled into Manhattan and I remember all the sights and sounds of that amazing metropolis, and I absolutely fell in love with New York. I was so excited--I walked down the street as soon as I got off that bus and I could feel my feet pounding on the pavement. It was like the energy of the city. I never ever arrived anywhere in my life, for the first time, and experienced that level of excitement. So there began a love affair with New York.

“Now, 35 years later, after having gone back and forth for all those years, I’m still in love with the place. But when I first heard about the story of Hart Island, there was a sense that I had learned in this interim period that New York wasn’t just about all the bright lights and the skyscrapers, but there was a darkness that lurked behind those streets. So when I heard that story about Hart Island, I realized that here was an opportunity to tell a story about the people that get caught under the wheels of the American dream. And for me, I didn’t want to celebrate the wealth and success of New York that made up one of my early experiences, but I wanted to dig deeper in the darker crevices because I felt that while New York was glorious in many ways, it has many dark secrets. There were many things about it that were harsh and lack compassion, and I felt that while I still love America and what it stands for, there’s a part of that harshness and dog-eat-dog mentality that I really struggled with. I realized that there were many New Yorks, and it wasn’t just the glorious New York that I was first drawn to. Now, I was more drawn to the darker part of New York, and to see what that darkness revealed about the soul of America. So that’s what propelled me to make the film: To look at the dark side of New York, and hopefully find something in there that resonated with me about the soul of American today.”

GU: “That’s great, because being from that area and having lived in America my whole life, I find that people from the area sort of roll their eyes at others’ romantic notions of New York City as this glittering metropolis, this City of Dreams where the streets are paved with gold. That myth is very much alive and certainly works out for people, but New York also eats people. Like any place, it’s not perfect for everyone, so it was really great to see that reality depicted in a film, because it’s a love letter in a purer sense of the word: To write any love letter, and to truly love a person or a thing, you have to acknowledge both the darkness and the light, and you certainly accomplish that.

“I wanted to ask: You certainly have a tremendous compassion for the people in New York, or even just for people in general, and that is evident in the way that you shoot the film and the intimate way you frame the subjects. In that final scene in the de Jesus family’s apartment, you framed the children in a way that was clearly enabled by having reached a certain level of comfort and trust. Could you talk about how you developed this relationship with your subjects?”

BB: “As we said, the film is a love letter, but it is a love letter with tear stains because New York is a heaven only for those who have money. It’s a hell, and one of the hardest places to survive if you are poor. So within all of that and within the stories that I chose to tell in the film, I realized that there was a great human spirit in each of the people whose stories I wanted to tell. And as a filmmaker, you have a responsibility to tell these peoples’ stories because in many ways, those stories go unheard. I’m trying to give a platform to those people so that their stories are heard, their experiences are felt, and so that they are felt more widely by raising them above the noise and the din of the music that plays in New York normally.

“So, you talk about Katrina’s [de Jesus] apartment, and I was there many times. And it was amazing to see the little shrine that was devoted to her child in an apartment that was otherwise bare and in many ways spacious--it’s got no furniture, just a mattress on the floor, really--and to then see one of her children dancing like a ballerina on the 13th floor of a Bronx apartment. I also then chose to put a bit of music there, and to put a choral voice there, and what we were trying to do was give these people back a bit of dignity that, in some ways, their experiences with the city had taken from them. That is a key thing I am trying to do in the work, so it is key to gain the trust of the individuals that you’re working with so that they allow you into their home. When you’re in their home, you get to see those moments and those images, and then you can capture those images of those people. So that was important for me in her story.

“In Kimberly Hudson-Bradshaw’s story,I wanted to bring her back to the place where she saw her father for the last time, which was on that boardwalk in Seaside Heights, New Jersey. And I wanted to juxtapose the summer beauty of a seaside town, filled with memories of childhood and fun, with her coming back to tell her story and walk along that boardwalk once we’ve started to unfold her story. It just so happened to be a rainy day, and the rain and the wet boardwalk are metaphors for broken dreams of her life. We see her as both a child on that boardwalk and, later, as an adult with those shattered dreams. That was an important image connection for me.

“With Herbert, it’s to see his pride in carrying the flag for his country, which is a country that has struggled so hard to accept him for who he is, and to treat him as a man and not as a slave, and not to treat him badly for the color of his skin. That was also a way of depicting his pride as an African America, as an American, but also the complicated, knotted nature of his story.

“For Hilda, the importance for her was to establish her in her homeland in Cuba, and to see the modesty and the poverty, in some ways, that she lives in. Then we paint the portrait of her father, who went away only to survive. And then it was important to bring her to the US, and place her in the majestic, commercial, garish beauty of Times Square, which can also be oppressive, and to see her witness that. We were to see her find and bring her father’s ashes home, and then see her meet her brother again back in her home, and realize that her father went away to try and achieve a dream for them as a family, and then perhaps got lost maybe looking for his own dream. Seeing her be able to bring her father’s ashes back and spread them along the water in Cuba, just outside Havana, was a powerful and fitting ending to the movie both for her and to try to give audiences a sense that despite the darkness, for some people there is hope.”

GU: “Right. I was just in Cuba for a month this summer, and it’s a magical country. I also wanted to ask you: I’ve noticed that you have a prominent thread in your work, including your past work like Bobby Sands: 66 Days (2016) and Maze (2017). You seem to be particularly interested in representing underrepresented populations, and I was wondering if you could talk a bit about that and how it relates to your next project, which is fittingly called Hear My Voice.

BB: “I did a lot of high-end TV documentaries for twenty years, but I think that the signature work that really launches my documentary feature career is Bobby Sands: 66 Days, which you can see on Netflix. So I made this film about Bobby Sands, and I thought about when I was 15 years old, growing up in Belfast. I went to school in West Belfast, which was sort of the epicenter of the conflict, and Bobby Sands came from West Belfast. I remember all the protests around the hunger strikes, especially in 1981, when he died. That was probably the most momentous year of the second half of the twentieth century in Irish history. 1916 and 1981 are the two seminal years in the twentieth century of Irish history. Anyway, I remember when I was 15 year-old schoolboy coming home on the bus from school, going through West Belfast, and looking out the window of the bus and seeing all the protests, knowing that Bobby Sands was on hunger strike for 66 days, and knowing that I came from the same republican community--though I didn’t get caught up in any of the violence or anything like that. I then, 35 years later, wanted to make sense of what that 15 year-old schoolboy was looking at. So, going back to tell the story of Bobby Sands was very important, because for me it was to try to make people understand something which is very important but also very controversial. For some people, Bobby Sands creates as much antipathy and disgust as it does empathy and concern in others. In many ways, I grew up with many people in a working-class Catholic family in Belfast who joined the IRA and killed people for that cause. I don’t stand by that, and I couldn’t kill anyone for any cause, but the thing I had to explain to people was that you couldn’t just call any IRA guy a cold-blooded murderer. I wanted to make people understand that with regards to somebody like Bobby Sands, who chose to starve himself to death for something he believed in, there is a value in that life. We must understand the circumstances that created him, because Bobby Sands did not grow up to become an IRA man or a murderer--he was created by the circumstances around him, and he reacted to those circumstances. So for me, he was an important emblem to be able to understand and to contextualize Irish history. It was my way of bringing the knotted, 100-year, torturous history of Irish conflict and bloodshed: I chose to tell that through the story of Bobby Sands.”

GU: “That’s a fascinating and gripping choice. Bobby Sands is definitely an important figure that stands out in the conflict--In my history undergraduate, I wrote a thesis paper on the Troubles that analyzed Bobby Sands’ writings.”

BB: “Right, that’s much of my film. To jump forward then, I’ve just finished a short subject documentary called Hear My Voice, and it’s a film based on a series of 18 portrait paintings by a world-famous portrait artist named Colin Davidson. His exhibition of paintings was called Silent Testimony, and it was a very moving experience to see these 18 paintings on a museum gallery wall. And what I realized was that while I told many stories about the Irish conflict, I had never told the story from the perspective of those who had suffered loss. To a certain extent, of course, Bobby Sands had suffered the loss of his life, and his family suffered loss as well, but there were also many who suffered at the hands of the IRA. These portrait paintings are of people who are still alive, in 17 out of 18 of those cases, who have either lost a loved one or who were injured in the conflict. And what I realized was that their loss didn’t end when they lost their loved one 30 years ago--they are still suffering today. And what I wanted to do was make a film just using these paintings, through a cinematic exploration of the paintings.

“So I re-hung these paintings in a disused warehouse in Belfast. I hung them in this old, beautiful space, and they were suspended in this space almost like the ghosts of their lost loved ones. It’s a 23-minute film which is being qualified for an Academy Award, and I’m going to New York and LA to screen it for Academy members next week. Because the exhibition was called Silent Testimony, in Hear My Voice I wanted to give voice to the peoples’ stories in those paintings. But I chose not to do any interviews on camera--I only did audio interviews with them, alongside a visual exploration of their painted faces. I wanted to bring a story of loss to an audience. I hope that, while bringing attention to these stories of loss in conflict in Ireland, the story also has resonances for those who have suffered loss in conflicts throughout the world, be it Syria, the Bataclan theatre, Berlin, or mass shootings, And in these faces of people who have suffered loss, I want to show that this what loss looks and feels like, and it never goes away. And so Hear My Voice tells that story.”

GU: “Right, and one of the details I noticed in One Million American Dreams was the heavy presence of loss in the film. For instance, there is a family photograph where Kimberly is sitting on her father’s shoulders, and the Twin Towers are in the background. Was the inclusion of that intentional?”

BB: “Well, they were family photographs, and of course as soon as I saw them I felt that we had to include them. And part of that is the idea of Bruce with Kimberly up on her dad’s shoulders, and yes--it was taken before the Twin Towers fell. It was quite an image to see them in the background, and in that moment we can see the pregnancy of the loss that occurred in those buildings some years later. You can look at the New York skyline throughout that film, and the absence of those towers is very emblematic of that loss. That’s another kind of subtle visual sense of loss that goes on throughout the film, and I suppose that theme is very alive in One Million American Dreams, and certainly in 66 Days, and it is explored again explicitly in Hear My Voice. So I suppose that while as a person I am generally regarded as a happy, ebullient person, as a filmmaker I am drawn to darker stories and stories about people who have lost something. As a filmmaker, above all else, I want people in the cinema to be moved by the human experience, so those are the sorts of stories I am always drawn to.”

GU: Right, it’s interesting to think about those things. I was 6 years old when the towers fell, but I remember it very clearly because I was very close, you know? And I was nearly moved to tears several times during the film because New York does have this sense of change, and with that comes some sense of loss. The New York skyline does not look the way I feel it should, and even my mother, who grew up in New York, talks about how so many building just aren’t there anymore. It’s jarring. I think we’re feeling that especially now, with the prevalence of gentrification and the pushing of people to the fringes.”

BB: “Oh, absolutely. Like I said, New York is a city for the very rich, so with gentrification there’s less diversity, less richness, less character in terms of the people who now live in Manhattan. With rents as high as they are, there’s nobody who lives in Manhattan that’s depicted in the film--they live in New Jersey, or Queens, or the Bronx. If they were living in Manhattan, they probably wouldn’t be in a Brendan Byrne documentary because they wouldn’t have a loved one buried in an unmarked grave on Potter’s Field--which is only 15 minutes from the Empire State Building. So I think that Manhattan has pushed those poorer people out to the margins, and that’s another thing the film was trying to draw attention to--again, not explicitly, because we’re not tackling that issue head-on. But I think it’s quite clear that the people who are featured in the film are not those that wear the suits and walk around with lots of dollars in their pocket. They’re searching for the American dream.”

GU: “And that’s a huge topic back home: New Yorkers just can’t afford to live in New York anymore.”

BB: “No, they can’t.”

GU: “Before I wrap up our interview, you said that you want people to leave the theatre with a sense of hope after seeing One Million American Dreams. At several points in the film, the statement ‘I want the truth’ is repeated by several of the documentary’s subjects in several different ways, and it sounds like a subtle rallying cry. Do you want people to walk away from this film feeling mobilized, or energized with a sense of duty? If so, to do what?”

BB: “Well, in some ways it’s a fine line, because in the early stages of the film I had to make an important decision about whether or not this would be a campaigning film. So in some ways, you’re touching on themes that are in the film and are a sort of call-to-action. In the end, you see the politicians talking about how they’re trying to move jurisdiction over Hart Island from the Department of Corrections to the Department of Parks, saying that they want to make it a public sort of place. But there wasn’t enough of an actual campaign that you could follow in the sense of making this into a campaigning film, so when I realized that there wasn’t a real opportunity to do that--and I wish there was, because I think I would have followed that direction--I then decided to make it a more contemplative and poetic film which was concentrated on the lived experiences of these people as they told their narratives, against something of a portrait of their daily lives lived in New York City. So for me, it’s an essay film that I want people to look at, think about, and linger on for many years to come.

“So I’m not looking for a quick-fix, and I think that the film will be around for a long time. It’s not a film that is going to have people queuing around the block to see it, and it’s not a very commercial film, but I think that it’s going to find its own fate. And hopefully the important people that might see this film--if it’s Mayor de Blasio or other influential people in New York--but somebody who’s somewhere may see this film. And they can and will do something about it to right this wrong, and to restore some dignity to this great city so that it begins to honor appropriately and respectfully its dead, many of whom toiled and worked hard to build the American dream that others currently live and enjoy. And we can celebrate the lives and regain dignity for those who got lost in the pursuit of that dream.”

GU: “What you said actually reminds me of Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York (2002), which has that tagline of “America was born in the streets,” and there’s even a scene at the end of that movie which depicts a cemetery that almost reminds me of Hart Island. It’s this idea that so much of history is lost by the stories that go unheard, and it’s touching when films acknowledge these stories, along with all of these darker parts of American history that we don’t necessarily like to talk about.”

BB: “There’s actually a shot in One Million American Dreams that analyzes the photography of Jacob Riis, and the key scene in Gangs of New York actually comes from one of the photographs that I have shown in the film. There’s an alleyway scene where’s there’s a bunch of guys…”

GU: “I know exactly what you’re talking about. It’s the Five Points, and they’re sort of sitting on a railing.”

BB: “Exactly, it’s the Five Points. That scene in Gangs of New York is based on the work of Jacob Riis, which leads me to believe that Martin Scorsese knows about Hart Island. Because he certainly knows about Jacob Riis, and Riis’ most famous work, How the Other Half Lives, ends up on Hart Island. So while the cemetery in Gangs of New York might not exactly be Hart Island, he may well have been influenced by that given the ending of the film. I’ll be checking that out.”

GU: “I’ll be doing that as well. Thank you so much for speaking with me today, and for this valuable insight on your film.”

BB: “Thank you!”

For more information about Hart Island, learn about the Hart Island Project at https://www.hartisland.net or visit https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/05/15/nyregion/new-york-mass-graves-hart-island.html