In This Section

- Home

- About Us

- Study with Us

- FMT Doctoral Studies

- Research

- CARPE

- Collaborations

- EDI

- People

- Film

- Music

- Theatre

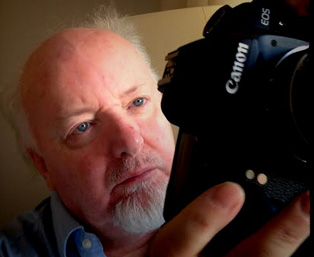

Blog. Interview with Irish Filmmaker Cathal Black.

Cathal Black is one of the most significant artists from Ireland’s “First Wave” of independent filmmaking during the 1970s and 1980s....

Over the course of his diverse and fascinating career, he has studied complexities and issues within Irish society through both narrative and documentary films (for more information, see (https://ifi.ie/cathal-black). This year, his newest documentary, Five Red Roses: One for Every Syllable of Your Name, was screened at the 63rd Annual Cork International Film Festival. The documentary explores Máirín de Burca, a prominent feminist and Irish republican activist, whose divisive yet gripping story is portrayed by Black in a poetic yet analytical way. After seeing the film, I had the opportunity to interview Black about his newest film and about his career more generally.

Gabrielle Ulubay: “Good morning, and thank you for speaking with me today!”

Cathal Black: “Thanks very much.”

GU: “To start off, I attended the Cork Film Festival’s screening of Five Red Roses: One for Every Syllable of Your Name, and I found it such an interesting documentary on both an informational and audiovisual level. Máirín de Burca, the subject of the film, is such a fascinating figure in Irish history. Would you mind speaking about how you came to make a documentary about her?”

CB: “I was kind of called into something many years ago, when I was offered the chance to interview a woman who had set up Attic Press, and who was very badly ill at the time, and later died. But I interviewed her and put together a small trailer that we could not, unfortunately, get off the ground. From then, it developed into something more than that. To be honest, there were a few times when I wanted to abandon the project, but we tried to make it a bigger, broader documentary about people like Máirín, Nell McCafferty, and people like that, and that kind of period. That didn’t take flight either, because of whatever the atmosphere in Ireland was like at the time--some people said that they’d covered it before, or they weren’t sure what the point of view was, or they wanted to sex it up or have a specific, named person walk us through the period. We tried to do that, and used a female comedian, but that got turned down. Then we tried another person, and it wasn’t going to work with her, either. I finally said that it was either going to work with Máirín or it wasn’t going to work at all. Now, someone else could have tried those things and make a different film, but I decided that I didn’t want to have a narrator who appears on screen every once in a while, because that could get a bit boring.”

GU: “That’s what I like about your documentary--I told you at the end of the film’s screening that I feel documentaries don’t have to be confined to a succession of interviews or voiceover narration. So while you certainly did a few interviews, I found your audio-visual choices very gripping. For instance, it really stood out to me when you had the audio of an interview in the background while we looked at a house with its lights gradually going out. Could you talk about what drove you to make some of those choices?”

CB: “Well, I didn’t really know what Máirín’s house was like. As a matter of fact, a lot of us thought that the house where she was brought up, in County Kildare, had been pulled down. We thought it was no longer there, and Máirín didn’t seem too keen on filming there. Then, a cousin of hers named Tomás, who was at the screening in Cork, let us have a look at it, and it was still there. That was very interesting because in my imagination, I had a clear idea of what the house was like: I thought it would be two-storied with old-fashioned staircases, and that wasn’t so.

“Now, once we arrived there, the problem was that we didn’t have much time to work with or to mull over what it was about the place that was so interesting. We found some old photographs that we put away in a trunk, and I thought that this house where she was brought up would be instrumental in discovering more about Máirín. She didn’t originally want to reveal much about her father and mother, but she did after a while, when she became comfortable with us. I thought that was a layer which, once brought out, would reveal more about the whole history.

“There also aren’t many archives in Ireland about that period in history. There are certainly photographs, and there have been books or bits and pieces written about it, but I wondered how we could visualize all of this. I thought, How do we get to the essence of all of this? Then, when Máirín talked about how she left school at the age of 12 or 13, then joined Sinn Fein at the age of 16 and would come home late on her bike, I found all of that quite captivating. So I took the notion of the house as, one one hand, quite romantic, but on the other hand as having a lot of unrest and a certain amount of sadness. So that was a great way to convey all of that.”

GU: “Right, and I think that all comes across quite clearly in the documentary precisely because of those audiovisual choices.”

CB: “Thank you.”

GU: “Could you talk about the process of finding actors to play Máirín at different ages? Did you have them speak directly with Máirín, or did she have a say in the casting? I imagine that it must have been challenging, because she’s a very complex person.”

CB: “No, it wasn’t a very difficult process. If you look at the two women who play her, they don’t even look like her at times. I paid more attention to Máirín when she was older, so the woman who is in her twenties was more important to me, whereas the girl on the bicycle was just a one-day shoot. I was trying to match the photograph that Máirín has of herself in her hallway, from her school days. So I thought that if I got someone who looked like that, then I could pull that off. But because of the way this film was made, it was only two or three people trying to piece it together. We didn’t have the luxury of a casting director, so a lot of it we just did ourselves. People did us a load of favors. In fact, there was a woman in Kildare who dressed the girl and found the bike for us, and then we went up to the house and shot what we could. Then we waited for it to get a bit darker, and shot that sequence with her walking with the bike. Nearby, there was actually a school with a little theatre attached to it, so we took footage of the Irish flag on the top of the stage, which is part of Máirín’s story as well. So, in a way, these were all visual metaphors that would probably take us through the story.

“The problem is that we had to cut what Máirín said down to its very bone, because there just isn’t enough time to include all of it. It was a question of being visually poetic, as opposed to moving the story along and making good use of time.”

GU: “I like that you brought up the necessity to bring the film down to its very bones, not only because of time constraints but because of budget constraints. Now, because I am writing for a population that will include aspiring filmmakers working with little or no budget, I was wondering if you could talk about what qualities a filmmaker needs in order to make films under such constraints.”

CB: “Just speaking from my experience with this film in particular, I found it useful to speak with just two or three people who would be in it for the long haul. I also avoided shooting nonstop for a full week and then getting maybe two days that are very good, while the rest of the week is very bad. That’s just the way I work. I think that you should try to keep it very tight and avoid letting the shooting go on forever, because if it does then all sorts of little mistakes can begin to creep in. Because we were flitting all over the place, picking up shots here and there, it might have been difficult for a large crew to keep up, so I tried to contain it and then find people to help locally.

“Now, sometimes we needed more people in scenes like the Mansion House, which involved about 40 extras. That was probably our most expensive day, because we had to go in, pre-rig it, shoot all day, feed people, and pay them. That was a much bigger operation, so we brought in 2 or 3 extra people for the crew, but in general we kept it pretty tight. It’s almost like some guerilla warfare: You go out, shoot for day or two, come back and assess what you have, and the prepare for the next time you go out. It’s exhausting and not a great way to work, because you have to refuel yourself every time, but in my experience it was the only way we could do it. You also need time to ask yourself, ‘What would be the best image for that?’ or ‘How can I best express that?’ I would think about things that Máirín had told me and wonder if that was a strand I wanted to go on.

“But one of the difficult things about doing documentaries is that you have to decide what the narrative is without just listing the things that the person has done. That is alright on paper, and even then looks a bit dull, so you have to consider how to bring some life into the material and what devices you should use to do that. An obvious way is to try to have enough photographs and archival material, and to have people talking, and to cross-cut between them. If you’re interested in this kind of material you would find that interesting, but if not then you might find that boring.”

GU: “That’s something that came up in the Q&A--the question of how relatable this material is for people who don’t know anything about it, or have nothing to do with the historical material. When you were filming, did you have it in mind that you wanted to make the topic universally interesting?”

CB: “Yeah, I think so. I mean, one could get into the entrails of the conflict in Northern Ireland, but that’s a very complicated, difficult area. And there are a lot of things Máirín said that people would find very offensive, even though that’s her point of view. You know, when recording this I tried to do justice to what she said, and it doesn’t matter whether I’m for her or against her, because I should be invisible in a certain kind of way. It’s not really my job to come down left or right of her. The aim was to make it so that ordinary people could follow this, without oversimplifying the conflict. There were times that I wondered whether I was skipping over things, but sometimes those are decisions that you have to make.”

GU: “And it’s very difficult to make those editorial decisions because, like you said, when making a documentary like this you have to remain relatively invisible. I want to bring that back to what you said earlier about a documentary taking on a life of its own, and how Máirín would say certain things that would make you consider going down a different strand: In terms of making this documentary or even making documentaries in general, could you expand on this tension between making editorial, narrative decisions and letting the material take on a life of its own?”

CB: “I’ve made both documentaries and dramas, and I find that making documentaries is much more fretful. It’s much scarier, because it can take a huge amount of time to find the sort of story you want to do. Also, you have to discover where the documentary leads you and when it begins to find its own energy. It’s a very difficult thing to describe, because the more you work on it the more you pare it back.

“It can be quite scary to take things away, but I find that the more information you take, the more the mind expands.”

GU: “That’s very interesting.”

CB: “Because the other solution is to just force-feed people information and the audience becomes passive, whereas I wanted people to be riding the journey with her. I wanted them to have a certain amount of feeling for her. You know, I wouldn’t be the best sort of person to make a documentary with just talking heads--I don’t think I could do it.”

GU: “That’s one of the qualities I appreciated most about the documentary: You captured what a gripping figure she could be, while of course acknowledging what a polarizing figure she could be.”

CB: “Right, yes.”

GU: “The way you depicted her made it so that, whether you agreed with her views or not, she was undeniably fascinating.”

CB: “Thank you. If that’s the way it’s working then I’m glad, because from my perspective it’s hard to know whether I’ve hit the right marks.After a certain point, you get thrown out your editing room because you need space from it. You find yourself making strange decisions in a short space of time, and our editing went over time--I gave myself a certain number of weeks, and it went another 3 or 4 weeks beyond that. I just found it very difficult to get the thing to fit, and I felt that I needed to be fascinated myself or I would get frustrated with it. I had to try to fit the scene with the televisions in, and to take those interviews and use them in an interesting, different sort of way. It didn’t all need to be from A to B to C to D. It could be small pieces of memory, and to me that was more interesting than creating a historical document of her life.”

GU: “Right, and it is working in the way you intend for it to work. To tie this in with your larger body of work, I know you’ve addressed a number of thought-provoking, often contentious subjects in other films of yours such as Our Boys (1981), Korea (1995), and Love and Rage (1998). What sparks your interest in these issues, and how to you determine whether you’re going to address them in a documentary or a narrative film?”

CB: “Well, to go back to Our Boys, that film was made in anger. It was something I felt I needed to do, and I wanted to set the record straight on certain things that were happening in Ireland that are still coming to light. It wasn’t shown on Irish TV for at least 11 years, and it was quite a short piece. The idea was to be subversive in that we used both drama elements and documentary elements, such as archival footage. We want to be subversive and to make a film that said ‘Sorry, but this happened and it was wrong, and we’re going to be living with this for centuries to come.’ I was schooled in the way depicted in the film as well, so I was familiar with the material.

“Korea, on the other hand, was made out of love for John McGahern’s short story. There’s an essential sort of dislocation in some of the work, which I find interesting. Anyway, Korea deals with America. It also deals with the notion of going to war, with policy, with legacy--where a father encourages his son to go to America, knowing that he might be enlisted. The father would get paid if his son enlisted, and if his son passed away.

“In a way, the films are about living in a world that I’m not completely comfortable with. I mean, I’m living in a country that I’m not completely comfortable with, but it’s always been like that. It was like that with Máirín de Burca in a way: I didn’t really understand her. I could appreciate what she did, and I was kind of fascinated by her single-mindedness, and yet on another level I wanted to see if there was a way of making this have its own truth, you know? So that you could transcend the historical material and turn it into something else. All my films are sort of like that: They seek to turn something sort of historical and uncomfortable into some energy, as though through some kind of alchemy, so that you can hit audiences in the back of their minds rather than necessarily in the front lobe.”

GU: “That’s very interesting, and that’s exactly what I was thinking about: how to find the common thread in a diverse range of material. Because the material itself is all very interesting.”

CB: “Right. For instance, I made a film about Thomas Lynch, who is a poet and undertaker who lives in Michigan. He found out he had some ancestors in Ireland, so he came back to County Clare and met this woman, Maura Lynch, who lived in a small cottage. He absolutely fell in love with the place and comes back every year, and he talks about journeys, the notion of being in Ireland, and the journey he then takes. I was fascinated by that--to put those two things together and to see what his point of view of Ireland was. I accused him once of being far too romantic about Ireland, but at the same time, that cottage in Clare is the same place where I once asked him, ‘Are we going to talk about the fact that you’re an alcoholic?’ You know, it was beautiful down there and I thought that would be the best place to talk about this.

“It’s that sort of strange brood that interests me. I think I would be very bored if I didn’t find images and sounds to mix things up and make something interesting. Because without that, you’re just lashing the stuff together.”

GU: “I agree, and you certainly avoid that pitfall. I really enjoy your work, and I look forward to seeing more of it.”

CB: “Thank you.”

GU: “On that note, you said a while ago that you were working on some new things before we started talking. Would you be open to talking about those projects that are in the works, or what you might be considering for the future?”

CB: “Sure. I have a script for a period drama that I’m hoping will work out. It involves the Second World War and certain royalty coming to Ireland, and what happened to them. That’s one thing.

“Another thing is a project about a woman who is with the Irish army in Lebanon, and she comes home because her daughter is shot dead. The drama is about us following her, and seeing where her journey takes us. In a way, it’s about modern Ireland, and the idea of coming back to a landscape that you don’t really recognize anymore. There are so many new people, and everything has changed, and the meaning of being Irish is up in the air--and that’s a good thing, in many ways. Those are the two projects--I’m staying away from documentaries at the moment.”

GU: “Yes, because you said it took you 8 years to do this last one!”

CB: “Right. Eight years from the time of trying to get people in it, getting it off the ground and then putting it down for a while, and then picking it back up and trying to get some heat in it, and then being told no. We were bringing the budget down, and it’s vile but that was in part because we were thinking ‘Will it get passed if we bring down the budget?’ Then, of course, you get the money and you’re delighted, but the reality of having to make the film with that amount of money is difficult.

“Now, when I say ‘that amount of money’ I don’t mean a couple of Euros. It was certainly enough, but when you’re bringing in scenes like the one with the televisions, and moving locations for different shots, you’re sort of asking for trouble with that budget--but we did it. In many ways, it was a miracle that we were able to do what we did.”

GU: “Yes, and it’s very impressive, and certainly something we can be inspired by.”

CB: “Thank you.”

GU: “To close out, I wanted to mention that I saw a screening of Pat Murphy’s Maeve at the Cork Film Festival, and she mentioned Our Boys as a landmark film that was made around the same time as Maeve. I thought to myself how exciting and interesting that was, because I had just met you at that point and we had decided to do this interview. It’s great to see the filmmaking community and Irish film history come together like that.”

CB: “Very good, yes. In some ways, I think that Pat is not being given the recognition she deserves. I know that her path has been quite difficult, but the problem about working in Ireland is that even when you make a film, and it’s well received, you feel a sort of pressure to reinvent yourself every time.”

GU: “Yes, I think that’s a pressure that a lot of artists face.”

CB: “Yes. There was no guarantee that just because you made something and it was good, you would get permission to do another one.”

GU: “That’s something many of us artists certainly find ourselves hyper-conscious of. Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me--so many of the other film students will benefit from your insight.”

CB: “Thank you!”