In This Section

- Home

- About Us

- Study with Us

- FMT Doctoral Studies

- Research

- CARPE

- Collaborations

- EDI

- People

- Film

- Music

- Theatre

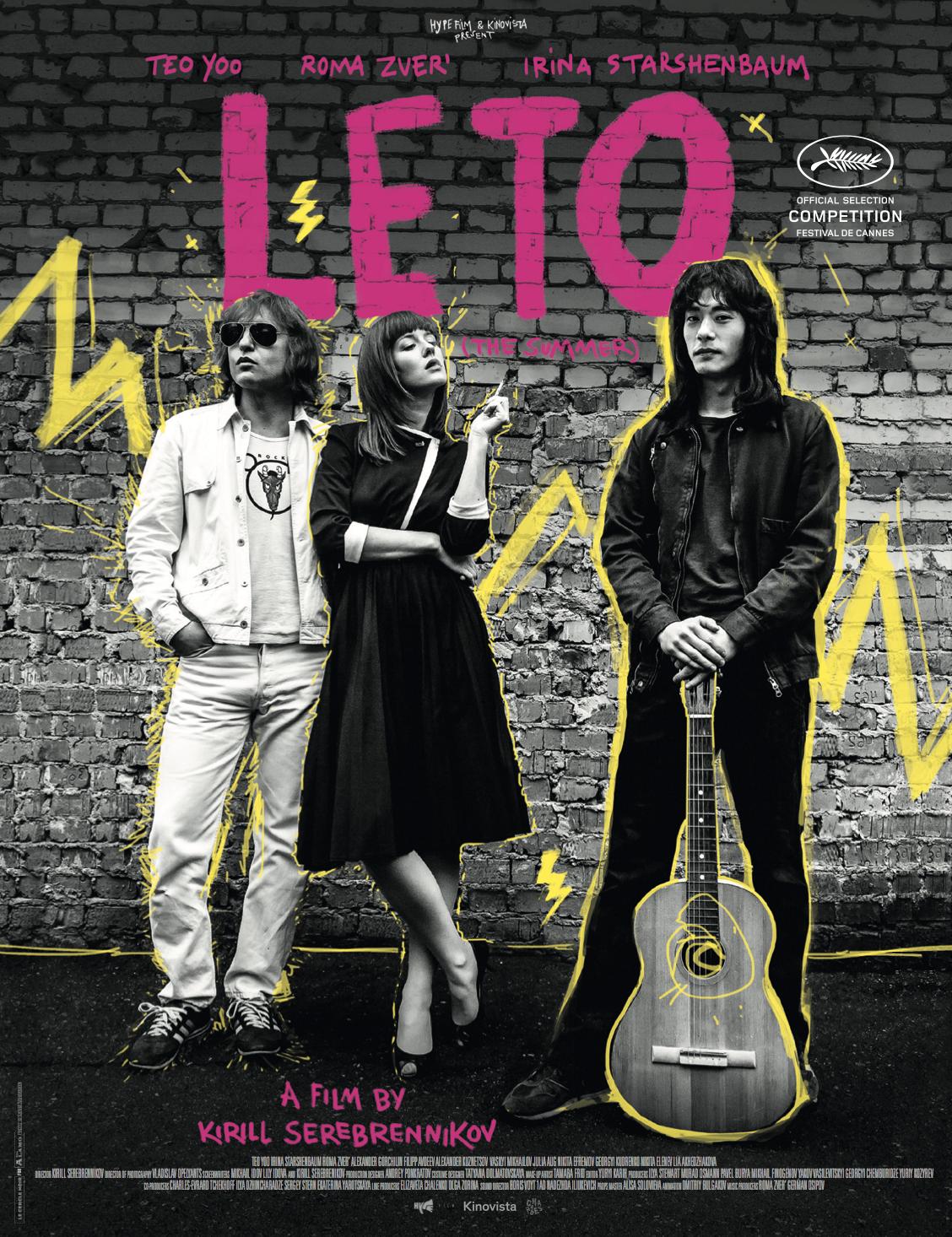

Blog. Cork Film Festival. 'Leto' by Kirill Serebrennikov

One of the first films I viewed for the Cork International Film Festival was Kirill Serebrennikov’s 'Leto'...

(watch trailer), an ode to the punk rock scene in Leningrad during the early 1980s. The film centers around the real-life musicians Viktor Tsoi and Mike Naumenko, as well as the latter’s wife, Natalya (called Natasha in the film), whose memoirs provide the basis for the script.

Based on my affinity for punk music, I sensed I would like this film and decided to see it the moment I read its synopsis in the festival programme. However, I could never have guessed how much I would love it. While my research indicates that the storyline deviates from what really happened between these people, the narrative was gripping and fascinating even as it moved slower than most mainstream films. For instance, the love triangle between the three main characters never culminates in any explosive argument, fight scene, or intimate encounter. Instead, the film is a contemplation about the nuances and complications that arise in relationships between restless young people who feel out of place. I would hesitate to even posit the love triangle at the center of the film. Instead, the film is about a youth characterized by beauty, melancholy, and yearning.

Similarly, the film also avoids dwelling on the harshness of urban Soviet life. When compared to other films that portray this era and its music scene (such as Atomic Blonde), the Cold War seems relatively peripheral. Instead of the overt verbal references to oppression or the dreary visuals that tend to characterize films about this time and place, Leto focuses on the microhistory of these individuals as they experiment and deftly navigate the limitations of their society. Communism haunts the film without heavily occupying space in it, making Leto relatable to anyone who has ever felt lost and out-of-place.

Visually, the film oscillates between black-and-white and color so as to highlight the sense of nostalgia. At the end, for instance, early scenes are replayed in color and appear to be home videos. The audience is pushed to reflect upon all that has happened since the first time those scenes played, in black-and-white, thus inspiring a deep sense of empathy with the characters. When we find out that Viktor Tsoi and Mike Naumenko die less than a decade after the final scene, we grieve as though we too experienced the film’s events. The sense of loss that accompanies the end of the film relates not only to characters but to the golden, almost magical period Leto depicts.

The film also sits between reality and fantasy, often spiraling into musical numbers of iconic songs such as the Talking Heads’ Psycho Killer and Lou Reed’s Perfect Day. During these numbers as well as other fantastical, unbelievable disruptions to the narrative, characters confront government authority figures, communicate with strangers, argue, and disrupt everyday city life. Then, well into these scenes, a “Cynic” character breaks the fourth wall and tells the audience (sometimes verbally, sometimes with a sign) that “this didn’t happen.” This could be a nod to the alteration of Natalya’s Naumenko’s memoirs, but I like to believe that it is a commentary on the gap between what we would like to do and what we actually do. Leto’s characters live in a confining world and, as members of a radical subculture, they do not always feel that they fit in or can fully express themselves. These fantastical scenes therefore draw attention to their disaffection and to the film’s nostalgic tone. After all, we often remember periods in our lives not only in terms of what happened, but also in terms of how we felt.

Report by Gabrielle Ulubay