In This Section

- Home

- About Us

- Study with Us

- FMT Doctoral Studies

- Research

- CARPE

- Collaborations

- EDI

- People

- Film

- Music

- Theatre

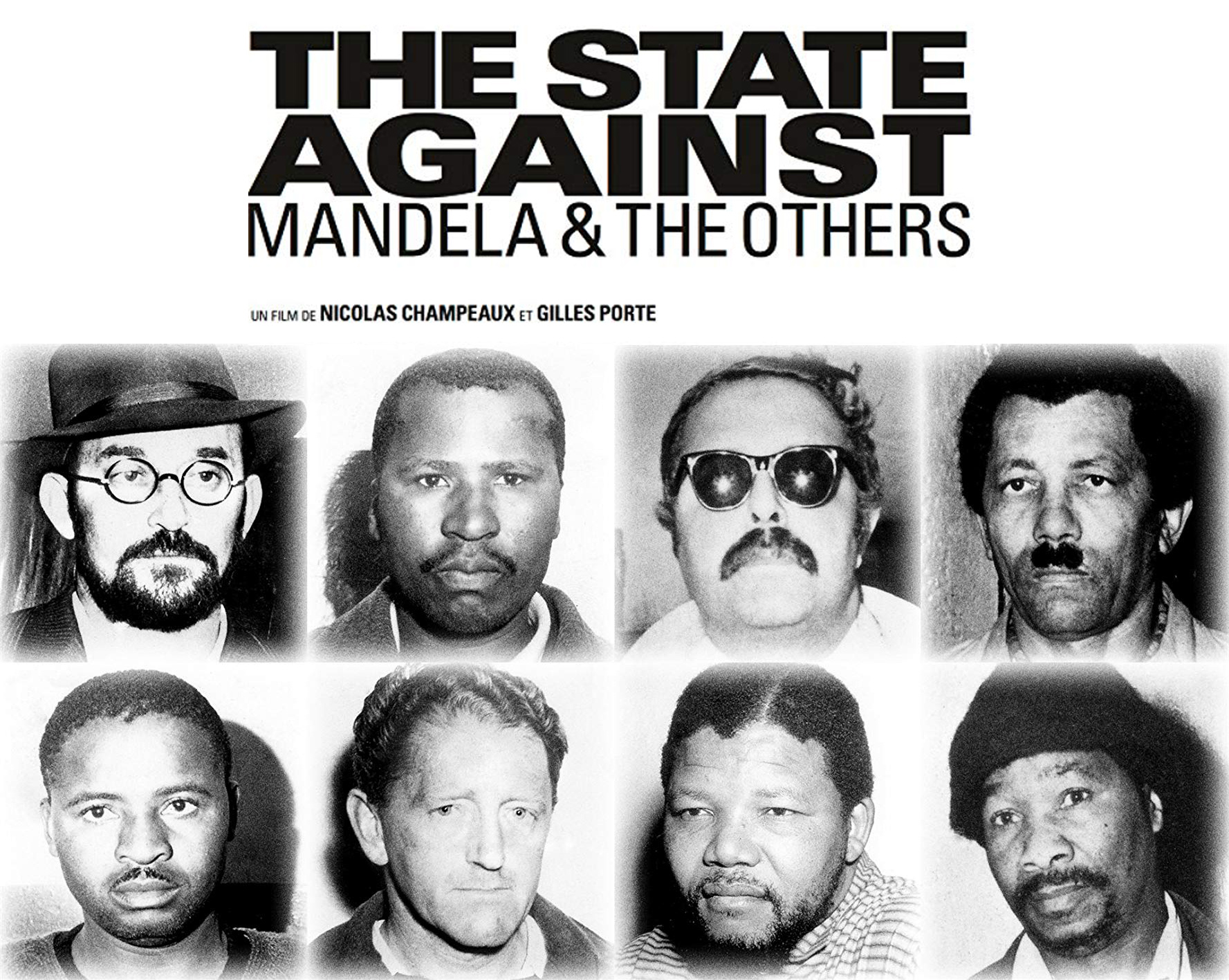

Blog. Cork Film Festival 'The State Against Mandela and the Others', a documentary by Nicolas Champeaux and Gilles Porte.

On Monday, as part of the Cork International Film Festival, I saw 'The State Against Mandela and the Others',...

a documentary by Nicolas Champeaux and Gilles Porte. Fortunately, Nicolas Champeaux attended the screening in order to give a short introduction to the film and a Q&A afterwards.

During the introduction, Champeaux discussed how he came upon the topic of the trial against Mandela and his fellow civil rights leaders during Apartheid in South Africa. Champeaux had been based in Johannesburg with Radio France between 2007 and 2010, and was able to listen to the 256 hour recording of the Rivonia trial, which prosecuted Nelson Mandela and 12 other anti-Apartheid leaders. Champeaux was stunned by the recording and planned to make a documentary about the trial, while at the same time there was a great deal of pressure on reporters in South Africa to interview Mandela and his associates before they died. In mentioning this urgency, Champeaux touched upon the relevance of an Apartheid documentary in contemporary society, observing that “the threat of white supremacy is re-emerging,” and that although Mandela and his associates’ particular struggle has ended, “it’s time for others to pick up the struggle. The children of Mandela benefit from his fight.”

Champeaux, of course, hesitated to approach his subjects by pointing out their mortality, so he waited until the 20th anniversary of Mandela’s release in order to interview them. He soon teamed up with Gilles Porte, who had emailed him with interest on the topic. Regarding the conception of this partnership, Champeaux quipped, “Sometimes if you want to make a documentary film, all you need to do is read your emails.”

Champeaux and Porte felt that the other accused members of Mandela’s circle had amazing experiences, but received relatively little recognition. Therefore, they sought to promulgate these stories by creating a documentary about the common thread of the Rivonia trial, shedding light not only on Mandela’s circle but also on the far-reaching horrors of Apartheid. In both his introduction and his post-screening commentary, Champeaux pointed out the importance of Rivonia as a historical moment. “They took the Apartheid regime on trial in that trial,” he said.

The film itself was a fascinating expansion on the trial, oscillating between actual audio from the event and the personal stories of those involved. Champeaux and Porte even interviewed the loved ones of the accused—most notably Winnie Mandela and Ahmed Kathrada’s former girlfriend, Sylvia Neame. The interviews were especially affecting during the moments in which the subjects listened to the trial’s audio for the first time, stunned into silence, nostalgia, or even tears. On the whole, the juxtaposition of the trial’s audio with the subjects’ reactions added rich, poignant detail to the harsh reality and injustice of the Rivonia trial. For me, Sylvia Neame was one of the most fascinating yet tragic figures in the narrative: She fell in love with a man of color, was forbidden by law to marry him, and was put on house arrest while he was imprisoned for life. Desperately desiring a child, she married another man while Kathrada was in prison, and still was unable to conceive. When Kathrada was ultimately released, she saw him for the first time in 26 years, and he later married another South African activist, Barbara Hogan. “That’s life,” Neame says wistfully in the film. “That’s life.”

The trial’s audio was accompanied by beautiful, seemingly hand-drawn animation which illustrated the events in an emotional, sometimes humorous, way. During the Q&A, Champeaux mentioned the difficulty in illustrating the audio because of the lack of photographs of the trial. Being a self-proclaimed “radio man,” Champeaux admits that he frames films around sound, while Porte frames them around visuals. The two artists came together in creating this animation, which was based on the drawings of the wife of one of the accused men. This animation prevents the documentary from inciting boredom or over-saturation of devastating historical information, yet at the same time its origins ensure visual authenticity. Champeaux told the audience that the animation was split into three categories—courtroom, metaphoric, and abstract—and was meant to both give the audience a sense of Apartheid’s intensity and highlight the outrageously theatrical nature of the trial itself.

During the Q&A, Champeaux also emphasized the sense of urgency behind making the film. He said that as Nelson Mandela and other anti-Apartheid activists died, there was a “real sense of history passing.” In fact, Ahmed Kathrada passed away two months after his interview with Champeaux and Gilles. Champeaux particularly mentioned the tension between urgency and funding, because he and Porte, having nearly run out of funds, had to decide whether or not they would delay their flight in order to interview Kathrada one last time. Champeaux also talked about the time-consuming and expensive nature of animating the audio, which took one week per cinematic minute.

Still, however, Champeaux stressed the priority of shooting the film before achieving total monetary security, implicitly extending advice to all aspiring filmmakers. “If I’d waited,” he said, “I wouldn’t be here.”

Report by Gabrielle Ulubay