In Safe Hands

The INFANT Centre at UCC is renowned for its world-class research focused on improving maternal and child health. One of the centre’s most exciting projects is pHetalSafe, a fetal sensor developed to detect and prevent a condition called fetal hypoxia. Here, Sarusha Pillay, commercial lead of the project, explains how this novel technology could potentially revolutionise obstetric care. In conversation with Marjorie Brennan.

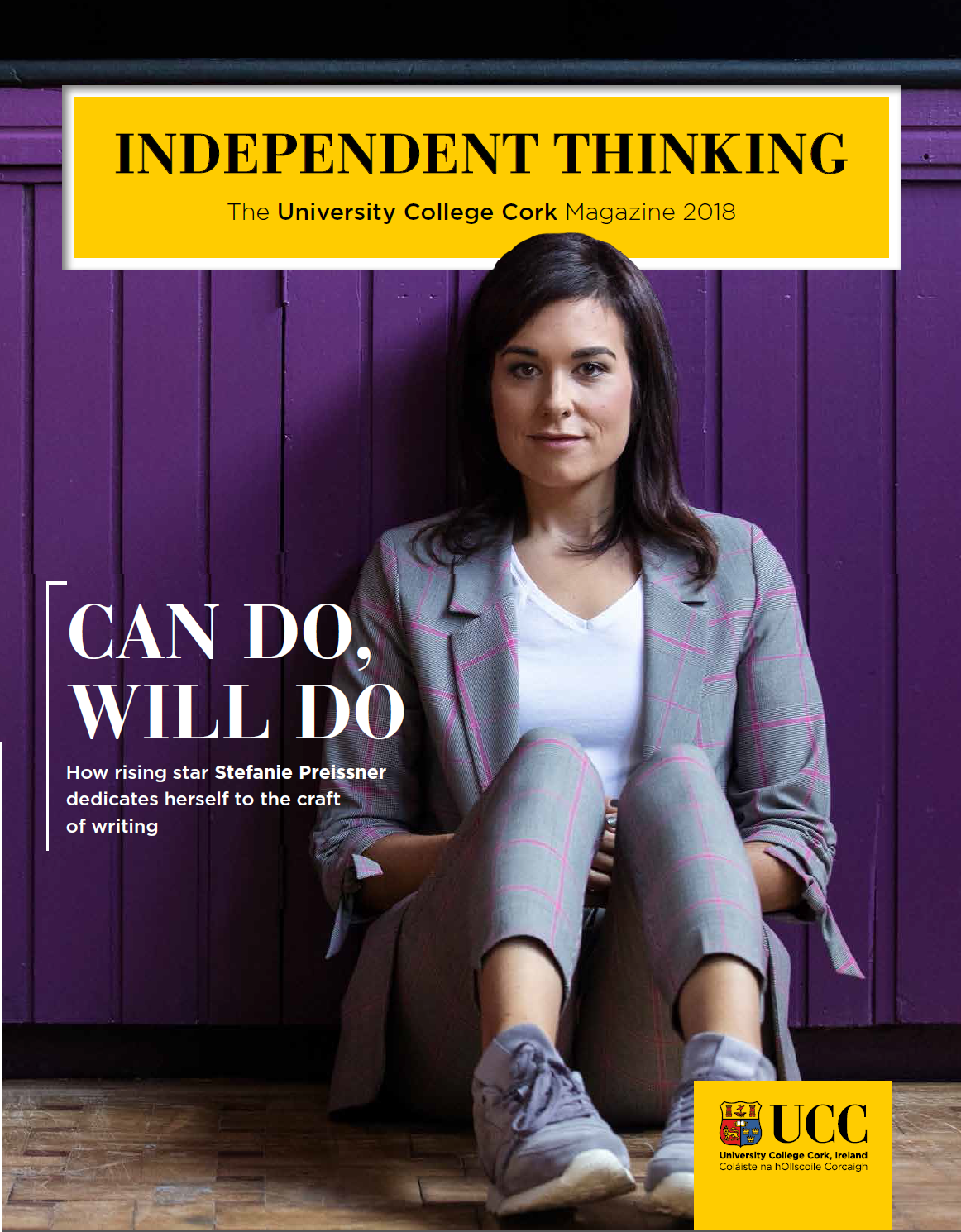

.png)

Since its establishment in 2013, the Irish Centre for Maternal and Child Health Research at UCC, known as INFANT, has become a hub of world-leading research and innovation, working to provide better outcomes in pregnancy, birth and early childhood. One of the most exciting research projects currently underway at INFANT is the development of pHetalSafe, a fetal sensor to detect and prevent fetal hypoxia – lack of oxygen to the brain at birth. This condition affects almost 200 babies in Ireland each year and results in death or disability in more than one million infants each year globally. It can also cause brain injury and leave newborns with permanent neurological damage.

In July, the project received a boost with the news that it had been named first runner-up in the IDEATE Ireland business plan competition. Principal investigator on the project is Dr Fergus McCarthy, a consultant in obstetrics and gynaecology at Cork University Maternity Hospital (CUMH), maternal fetal medicine sub-specialist and a lecturer at UCC. Commercial lead on the project is Sarusha Pillay, a previous recipient of a BioInnovate Ireland Fellowship.

According to Sarusha, the collaborative nature of INFANT gives it an advantage in terms of progressing clinical research: “The centre has a very strong partnership with the maternity hospital [CUMH], which gives it a clinical edge and access to obstetricians, gynaecologists, paediatricians, neonatologists, and so on. That positions it from a research centre perspective as unique because many research centres do not have the proximity to clinicians that INFANT would."

She says the current means of fetal monitoring, the cardiotocograph or CTG, which comprises two belts that stretch across the mother’s stomach, has been in use since the 1960s and is no longer fit for purpose. According to Sarusha, CTG readings can be difficult to interpret and highly subjective from user to user, resulting in misdiagnosis and suboptimal care.

“If we had a better instrument, then obstetricians could make more informed decisions on a personal level for the patient,” she says. Which is where Fergus came in. His initial idea came about because, while lactate and pH are at the core of fetal acid base balance and wellbeing, they are currently unmeasurable in a non-invasive manner during labour. The proposed minimally invasive multi-modal fetal sensor aims to provide continuous real-time assessment of lactate, pH and other key physiological variables including fetal heart rate and temperature during labour. The technical development of pHetalSafe is being carried out in collaboration with the Biophotonics group in Tyndall National Institute at UCC.

Next July, the team will have a protoype for early-stage validation data. While there are still many hurdles to be overcome in terms of funding and development, Sarusha says it is hoped that the pHetalSafe monitor will eventually have real-world application on a global scale. She says the device is needed now more than ever given that patient risk profiles all over the world are increasing – women are having babies at an older age, obesity is on the rise, and pregnant women have more co-morbidities than before.

As well as having the potential to revolutionise obstetric care by ensuring fetal wellbeing, the pHetalSafe monitor could also have positive effects in other areas, according to Sarusha. There is a strong business case for the device in terms of tackling the current complexity of interpreting results which makes hospital workflows cumbersome and inefficient. There is also the prospect of reducing the risk of liability and litigation, which leads to problems in recruiting and retaining staff. However, it all boils down to improved outcomes for mother and child, she says.

“You need to also equip obstetricians with a tool where they can feel more confident to do the job that they need to do. It is about the patient, standard of care and wellbeing – delivering babies safely and giving them the best chance of a fruitful life. pHetalSafe improves the standard of care for the patient. It also gives patients more confidence that they’re going to have a better birthing experience. Patient mobility is also a big thing as people don’t want to be bed-bound because of the CTG. Our device aims to promote patient mobility by giving them more freedom.”

"When you are looking at the impact this could have, it’s huge. It’s the start of life, the make or break of our wellbeing" - Sarusha Pillay

The pHetalSafe device could also benefit countries where there are additional challenges in terms of monitoring babies and mothers.

“The other cohort of people that really need this device are those in countries with a high HIV/AIDS rate,” says Sarusha. She explains how current devices, that are adjuncts to CTG, hook onto the baby’s head or blood is drawn from the baby’s head via a tube, in order to check the pH level. “If you’ve got HIV-positive mothers, you cannot do that. So, all those doctors who only rely on CTG, they don’t have options. Ideally, over the long term, we want to be able to help those areas like Africa and India with high HIV rates and give them a tool that’s more effective.”

It is hoped that after clinical data has been gathered, pHetalSafe will spin out from the university in the first quarter of 2025, when venture capital and angel funding will be sought. While the road to implementation is by necessity a long one, Sarusha says it is all relative in terms of the final result.

“It seems like a long time, but if you think about the lead time for med-tech implementation, it’s 10 years plus. It’s just about going through the steps, making sure that we stay on course. And when you are looking at the impact this could have, it’s huge. It’s the start of life, the make or break of our wellbeing.”

For more information, visit the INFANT Centre’s dedicated website.

Photography: courtesy of IDEATE Ireland