Features

- Life beyond cancer

- Neil O'Leary, Chair of Cork University Foundation, on a successful career and what motivates him to support UCC today

- A point in time: coastal Atlas will serve as ‘a record for our grandchildren’

- Coming up for air: the sport of the novel for Eimear Ryan

- Sprinting forward

- A welcome return

- Time for positive change

- UCC students and alumni shine on the biggest sporting stage

- Adapting to the current

- It takes two

- Climate change requires transformative social action

- Bridging the gap

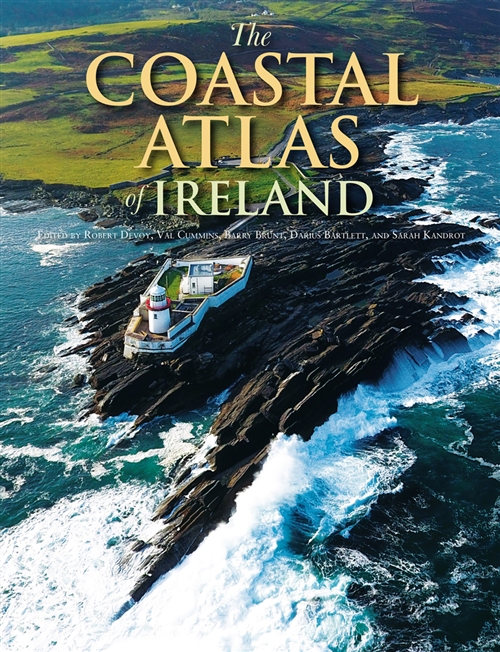

A point in time: coastal Atlas will serve as ‘a record for our grandchildren’

Lorna Siggins uncovers the rich stories and inspirations behind the latest masterpiece from Cork University Press, The Coastal Atlas of Ireland.

When Dr Valerie Cummins was studying marine geography in Wales, she remembered poring over a particular publication in her local bookshop.

It was The Times Atlas of the Oceans, first published in 1987, and its contributors included some of her lecturers at Cardiff University.

It struck her as “such a beautiful piece of work, with its text and cartography”.

“So it was wonderful to think that, so many years later, we could work on the same type of project, albeit much larger, here in Ireland,” Cummins says.

A “survival book for you and your children”, and “richly compelling” are some of the tributes which have already been paid to The Coastal Atlas of Ireland, published by Cork University Press (CUP).

The 893-page publication has been seven years in gestation since UCC Emeritus Professor of Geography Robert Devoy discussed the idea with Cummins. He had already compiled the Atlas of Cork City with John Crowley for CUP over 15 years ago.

“Initially, a core group was formed with UCC physical geography lecturer Dr Maxim Kozachenko, and we got some key authors together and devised how it would be structured,” Cummins recalls.

An expert in the field of coastal governance, ocean innovation and sustainability, she was director of the Irish Maritime and Energy Resource Cluster (IMERC) at the time. She is currently company director for the Simply Blue Group, focused on floating offshore wind development.

Devoy, who is Ireland’s leading expert on sea level rise, has contributed to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as a lead member of one of its working groups.

“I was born and grew up near the sea, it is where I spent much of my academic and research career, and so it has huge emotional value for me,” he explains.

“My idea, as part of my retirement from UCC, was a photographic series of the coast of Ireland,” he says. “However, climate issues are going to be with us forever, and they have been a part of my work for the past 30 years ….”

Cummins recalls how quickly the draft publication began to grow after initial deadlines were issued, and it became apparent it would need “project management”.

“So, I secured some external funding including donations stewarded through the Cork University Foundation,” she says.

This allowed for expansion of the team to include former UCC geographers Darius Bartlett and Barry Brunt, along with Sarah Kandrot who specialises in use of geoinformatics technologies.

Researchers Zoe O’Hanlon and Kyle Fawkes provided essential editorial support, searching out photos and images, and negotiating and tracking copyright permissions. The publication has over 140 contributors, ranging in expertise from archaeology to zoology.

The Atlas represents a “point in time”, Barry Brunt explains. While the geological past doesn’t alter – “though its interpretation might” – the urbanisation of the coast, impact of tourism and development of offshore resources reflect areas of rapid change, he says.

“The Anthropocene, where we are now, reflects the most transformative change and the enormous impact that we as humans have had in such a short space of time – and at such a cost. The coast is an enormous laboratory, where atmosphere, ocean and land converge” - Val Cummins

Brunt had gained a sharp, shocking early appreciation of man’s impact on the environment shortly after he began studying geography. He had just started first year at the University of Manchester in 1966 when he received a phone call he would never forget.

It was from his home village of Aberfan in Wales. One of the spoil tips attached to the local coal mine had collapsed after heavy rain, claiming the lives of 116 school children and 28 adults.

“I knew the teachers, and many of the children,” he says. One of those who died in the catastrophic slide was his grandmother.

Brunt is endlessly fascinated by the largely unspoilt nature of the Irish coastline. He believes anything less than over 140 contributions on its various aspects would have been “selling it short”.

“When you start unravelling the picture, there is a lot more than ecology, flora and fauna and offshore seascapes. Ireland has its cities which grew out of developing sea trade, and as we started to assemble the material we became more and more excited, and it was never a chore,” he says.

“Getting the spine right” became the watchword for the publication, given the different styles and approaches taken by authors. Weekly meetings were held without fail, the project was a “joy to work on”, and “we are all still friends”, the editors point out.

Climate breakdown is a dominant theme, and one which influences the pace and tempo of the text.

“So the text begins slowly with the geological forces which shaped our island and its coastline, the gradual settlement patterns through the ages, and then everything begins to accelerate,” Cummins says.

“The Anthropocene, where we are now, reflects the most transformative change and the enormous impact that we as humans have had in such a short space of time – and at such a cost. The coast is an enormous laboratory, where atmosphere, ocean and land converge,” she says.

The Coastal Atlas is dedicated to the late maritime historian Dr John de Courcy Ireland and to Bill Carter, former head of University of Ulster’s Department of Environmental Studies.

Darius Bartlett credits Carter for influencing his choice of academic career. Carter hired him to assess coastal erosion around Antrim, drawing on Bartlett’s experience of digital mapping and GIS.

“We tried to make it as comprehensive as we could, and I think we felt there was nothing we had no room for,” Bartlett says.

In his opinion, it is “almost impossible to truly understand the coast except in an integrated and completely interdisciplinary way”. Although his background was in the earth sciences, he particularly enjoyed the sections of the Atlas that looked at cultural and social issues.

“For instance, in our section on people and the coast, we have sea swimming, sand sculpting, the influence of the coast on the life and work of a painter by John Simpson, and its interpretation by dancer and performance artist Roksana Niewadzisz,” Bartlett continues.

“We have poets Pádraig Ó Tuama and Theo Dorgan between our end covers, and one section which I enjoyed particularly was on the coast of Ireland through film,” he says.

“We had always wanted to make it very visibly an all-island atlas, drawing in subject matter that covers the whole island. It also helped that I was able to consult my daughter, Becky, who is a specialist in that area and lectures in film studies at St Andrews University in Scotland,” he adds.

“One of the tragedies is that we didn’t have cartographer Tim Robinson, who died early in 2020,” he says. The atlas does carry an image of Robinson’s map of Arainn.

“The sea has infiltrated the Irish language in many ways, which Tim recognised,” he says.

Bartlett and his colleagues believe the visual element, which Sarah Kandrot worked on, is very much part of the publication’s strength.

“I view this publication as a record for our grandchildren, and as part of the solution, in its invitation to appreciate the coastal environment in all its beauty and complexity …” - Robert Devoy

Kandrot, an earth science graduate of Boston University, was finishing her PhD when the first Atlas planning meeting was held in UCC’s Western Gateway building.

“Sourcing data was difficult, and trying to put everything together in a way that flowed was also a challenge, but I think we have been able to weave short pieces, such as boxes and case studies, into the main chapter text,” Kandrot says.

“A lot of the material came directly from contributors’ own scientific research, but we also had to source material from many government agencies. The Marine Institute was extremely helpful in sharing data which is publicly available.”

Material provided by Infomar, the national seabed mapping programme jointly run by the institute and Geological Survey Ireland, was also a rich source.

Kandrot, who is now working with Green Rebel Marine on baseline survey data acquisition for offshore wind farm projects, co-ordinated the digital elements of the Atlas to produce a series of interactive maps in the form of a StoryMap, which aligns with the various sections of the printed work.

“This draws in other map layers, such as the satellite layer, allowing the reader to view different map features in the context of various types of environments, such as beaches, dunes or machair, at different scales,” she says.

Cummins took the western Pacific archipelago of Palau as a theme for the final chapter. An influence for this has been the Future Earth Coasts collaboration of international scientists, based at UCC’s MaREI (the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Energy, Climate and Marine) which she chaired for a number of years.

“Palau describes itself as a small group of islands, but a big ocean state. The challenge for us is to ask ourselves why we, in Ireland, are not talking about being a big ocean state,” she says.

Devoy has long been an advocate of integrated coastal zone management to plan for sea level rise, with the associated issues of flooding and erosion, and his research has pointed to the high resilience of many parts of the Irish coastline.

However, Ireland will also have to consider the concept of coastal retreat, he says. Low-lying countries like the Netherlands have already adopted this approach in some vulnerable areas while “building out” in others.

“It’s a complex management issue, and one which has to be linked to providing for people’s livelihoods where they may be under threat,” he says.

“The Atlas is a medium for prompting people to think about the implications of changing climate – in my view, the pandemic doesn’t even rate when it comes to the impact,” Devoy says.

“So, I view this publication as a record for our grandchildren, and as part of the solution, in its invitation to appreciate the coastal environment in all its beauty and complexity ….”

The Coastal Atlas of Ireland (€59) is available to purchase now from all good bookshops and directly through Cork University Press.

Details of the accompanying StoryMap project can be found here.

Launch event photography: Provision