Research blog: Beneath the surface of stress

Eadaoin Whelan, a PhD student in SoAP, blogs about the impact of daily stressors on health outcomes, which is the focus of her research. In the blog Eadaoin describes how daily stress, even relatively low level stress, can cause changes to health, in part through biological stress responses, and in part by changes in behaviour that happen when people become stressed.

Eadaoin's research focuses on adolescent health, and how the developmental period of adolescence is shaped and influenced by environmental stressors. Using the allostatic load theory, Eadaoin's research examines how emotional experiences are transformed into health outcomes, and scrutinises the unique contribution of both daily stressors as well as daily uplifts, an under-researched area of adolescent health. Eadaoin will use biological measures (stress hormones, immune system) to capture individual health profiles, and use these with measures of health behaviours (e.g. diet, exercise, sleep) and adolescent diary-reports of daily experience to examine the impact of experiences on health. Based on the findings of this research, Eadaoin will develop and test an intervention designed to buffer the effects of negative experience and amplify the effects of positive experiences. The findings will create new opportunities to promote healthful responses to experiences in adolescence.

Slept through your alarm? Friends haven’t returned your message? Have an exam coming up? Don’t have enough money to do what you want? All of the above?

These are just some examples of minor stressors that teenagers encounter on a day-to-day basis. Many teenagers experience stress as part of every life, some of might be considered minor, others may be major stressors. If you or a teenager you know had a day that featured any of the events listed above, now might not be the time to tell you that stress is in fact an adaptive response, which serves to alert us to potential danger in our environment. The increase in heart rate and blood pressure you may have experienced this morning, is just your body’s way of helping you prepare to meet these challenges! So stress isn’t that bad after all… or is it?

Most people, when they feel stressed, have changes in their body – their heart rate goes up, they might feel their temperature rise, they might get shaky legs, sweaty palms or butterflies in their stomach.

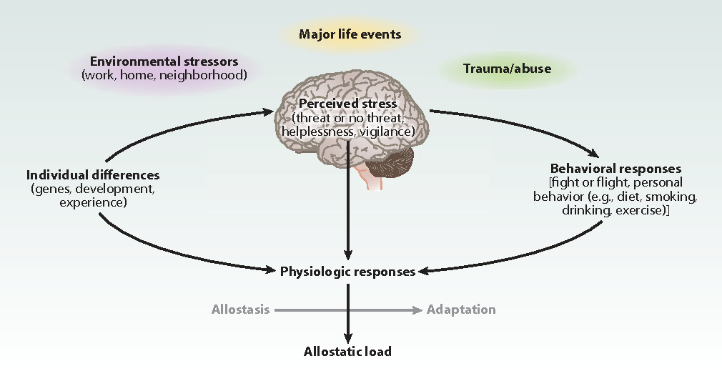

These are some of the ways in which our body responds to stressors, and people can feel some of them as they happen. However, these are all physiological symptoms, they occur internally, beneath the surface of our skin, and there are many other physiological stress responses which aren’t felt by the person. Individuals can be unaware of the impact of their response to stressors on their health – and there is lots of evidence that stress has short-term and long-term effects on physical health. As these stress responses are an inherent part of our daily lives, we must understand the manner in which our bodies respond to stress as it directly influences both our immediate and long-term term health outcomes. Although the person themselves may be unaware of the health costs that come from lots of stress, or repeated experiences of even minor stressors, researchers have described it as allostatic load.

Allostatic Load

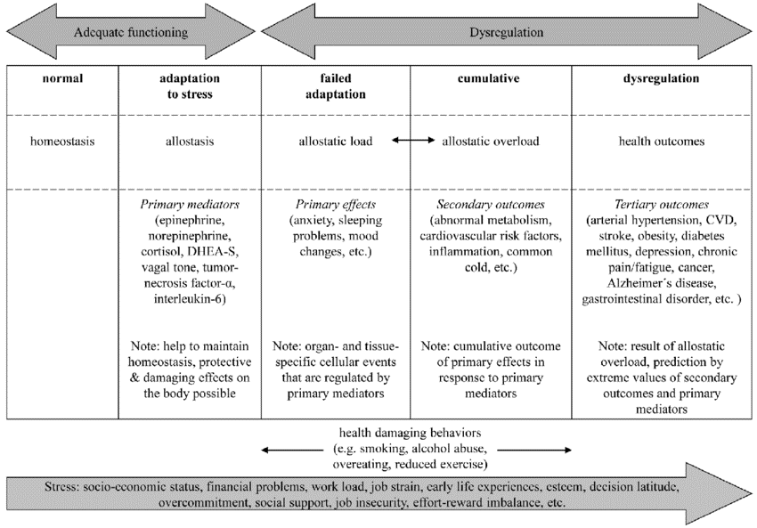

The stress response is adaptive, it gets our body ready to respond to environmental demands by activating and regulating physiological systems. This adaptive response is what scientists describe as allostasis. In order for the process of allostasis to occur, it requires the release of stress-related hormones in the body. These hormones are released when the stress response is triggered, and mostly consist of; cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine. However, inadequate, failed, lack of, or repeated activation of the physiological systems involved in releasing these hormones, contributes to a wear and tear on the body over time, resulting from being ‘stressed’. This wear and tear is what we then refer to as allostatic load. Allostatic load (AL) results from chronic dysregulation (that is, the systems stop working as they should) of the systems involved in responding to stressors, and it has been associated with the onset of chronic diseases later in life, and most of the research has been done on older adults. More recently there is some evidence that allostatic load may be present earlier in life – even in teenagers. However, there is still much to be learnt about how teens respond to stress, the kinds of stressors teens experience that may be different to adults, or different to teenagers in previous decades and the kinds of emotional and behaviour responses today’s teens have to stress. These are all important in understanding if and how teenagers may develop allostatic load.

Adolescents and Allostatic Load

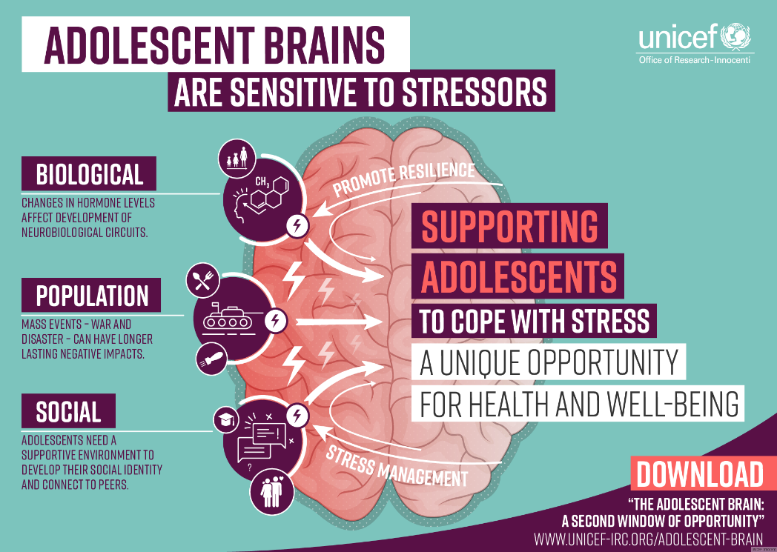

Adolescence is a period of significant change for all teens, there are changes in biological processes, psychological development, and teens through several transitions that affect how they think of themselves, others and their place in the world – and these in turn influence how they respond to stress. These changes are an expected part of growing up and growing older, but research indicates that adolescents may find it more challenging to regulate themselves, and so regulate their biological systems in a manner that supports good health outcomes. Adolescence has, in the past, been recognised as a period of risk, where individuals are more susceptible to developing habits which pose immediate and long-term threats to their health, but contemporary research describes adolescence as a period of opportunity, where teens are learning about themselves and new opportunities for good psychological and physical wellbeing can be realised.

Current Project

Improved understanding of how adolescents process and respond to stress is critical for translating research findings into interventions to improve adolescents’ physical and mental health. Stemming from the fields of both applied psychology and occupational science, a project led by Eadaoin Whelan, currently underway in the School of Applied Psychology, will examine the experience of stress in Irish adolescents. The project consists of four separate studies, the first of which is a review to investigate measures of allostatic load in adolescents. Once the initial study has been completed, the findings will be used to inform the biological measures which will then be taken from a sample of Irish adolescents, alongside measures of health behaviours (diet, exercise, and sleep), and self-reports of daily experiences. Based on the overall findings from study 2, in the latter stages, the project will pilot an intervention which aims to reduce the impact of stress on adolescents’ physical and mental health, and amplify the effects of positive experiences.

For more on this story contact:

Eadaoin Whelan is a CACSSS PhD Excellence Scholar and is supervised by Dr. Samantha Dockray (Applied Psychology) and Dr Eithne Hunt (UCC Department of Occupational Therapy and Occupational Science.