Freshwater Quality & Sediments Sampling In Western & Western North Regions Of Ghana: The Importance Of Observations In Water Quality Monitoring And Assessment

We are delighted to feature an update on the work of our MSc graduate Jeremiah Asumbere following his graduation. Jeremiah is currently with Ghana’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA Ghana), and is a graduate of both the PGDip and MSc in Freshwater Quality Monitoring and Assessment at UNEP GEMS/Water Capacity Development Centre. Jeremiah completed his dissertation with the CDC in 2020 (class of 2021!) and his current work focuses on both environmental and public health protection in freshwater bodies in Southwestern Ghana.

Managing Freshwater Quality in Ghana

In 2021, Jeremiah and his team at the EPA embarked on an ambitious project to monitor freshwater quality and assess levels of pollution from mining and agricultural activities in the Western and North-Western regions of Ghana. Their results will provide the necessary information to policy makers in order to set up the standards for soil and sediments in the area, and to inform further actions and management options of these freshwaters.

Fig. 2: Surface water is used directly as a drinking water source in many rural communities (c) Water Resources Commission.

Threats to Water Quality

With a growing population, increasing economic development and climate change, Ghana’s water systems are under pressure from various sides. Pollution in the form of numerous metals, nutrients, pesticides and other chemicals problematic to human and environmental health are released into the country’s waterways by industrial, waste and agricultural activities. At the same time, great parts of the rural population rely on these freshwater bodies as a direct drinking water source, that is without prior treatment of the water.

Fig. 3: Sampling soil and water at the Ankobra river before it joins the Gulf of Guinea.

Impacts of Mining on Environmental Contamination

A specific issue in Ghana are unregulated artisanal small-scale mining (ASM) activities, locally known as ‘galamsey’, which have often been linked to soil erosion, biodiversity loss and contamination of soil, surface and groundwater. In the gold extraction process, heavy metals such as mercury and cyanide may be used and released into the environment. The harm caused by ASM activities was officially recognised in March 2017, when the Government of Ghana banned uncontrolled mining throughout the whole country.

Developing a Water Quality Monitoring Plan

In August 2021, Jeremiah and his team a team of officers from the EPA Head office and regional EPA counterparts led by Jeremiah set out to investigate the real-world effectiveness of this ban.

Applying the expertise acquired at UCC, Jeremiah developed a water quality monitoring plan, identifying suitable water and soil sampling points. To identify suitable and representative sampling locations is of uttermost importance for a solid water quality monitoring strategy. During their campaign, the team measured metal levels and physico-chemical water parameters of eight water bodies in Western and North-Western Ghana. As with all water quality sampling activities, it is important to note observations that might affect the water quality in the sampling site.

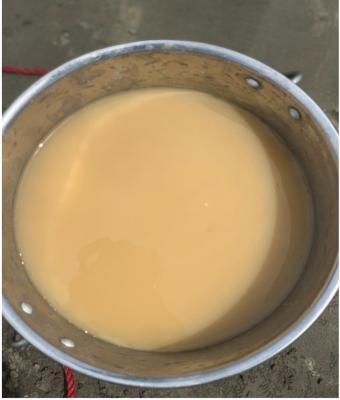

In most cases, this involves factors like weather conditions, but in the case of Jeremiah and the team, they also made many notes on any observable illegal mining activities polluting the rivers. Impacts of mining activities – visible by the discoloration of the water (Fig. 3 and 4) and reported by locals- could be found at almost all sampling locations.

Fig. 4: Coloration of water from Ankobra river.

Preliminary Findings

Some river systems were found to be under more than one pressure points: The Broma and Tano river, for example, were found to receive pollution not only from metal extraction, but also by ‘sand winning’ - often unpermitted or illegal sand mining. In 2019 and 2020, border officials at Cote d’Ivoire and Ghana have vehemently complained about the uncontrolled pollution of the Tano River that affects both countries. Other impacts on the rivers included water abstraction for agriculture such as palm oil production and close vicinity to waste dumps.

During the field campaign, Jeremiah and his team followed strict standard protocols for sample collection, storage and treatment, a skill Jeremiah was able to improve on during field work as part of his course in UCC. Jeremiah was also able to pass on his expertise on water and soil analysis on to regional officers, building local capacities and enduring connectivity.

Upon data analysis, Jeremiah and his team found high turbidity level and suspended solids in all samples collected, most likely due to runoff from mining and sand winning activities. Fortunately, levels for arsenic and cyanide were found to be within WHO guidelines, indicating the effectiveness of the two-year ban on small-scale mining.

Fig. 5: Jeremiah sharing sampling procedures with his EPA colleagues.

Impact on Sustainable Development Goals

Jeremiah also performed a risk assessment for public and environmental health. The data collected during the project will contribute to the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 3 - Healthy Lives and 6 - Clean Water. Jeremiah’s work provides a solid basis for current and future monitoring of freshwater bodies as well as future studies. The data collected can also be used to formulate policy recommendations and for standards on soil and sediment quality.

Fig. 6: Children are among the most vulnerable for water pollution in Ghana, and across the globe.

UNEP GEMS/Water Capacity Development Centre

UNEP GEMS/Ionad Forbartha Acmhainneachta Uisce

Contact us

Environmental Research Institute, Ellen Hutchins Building, University College Cork