Features

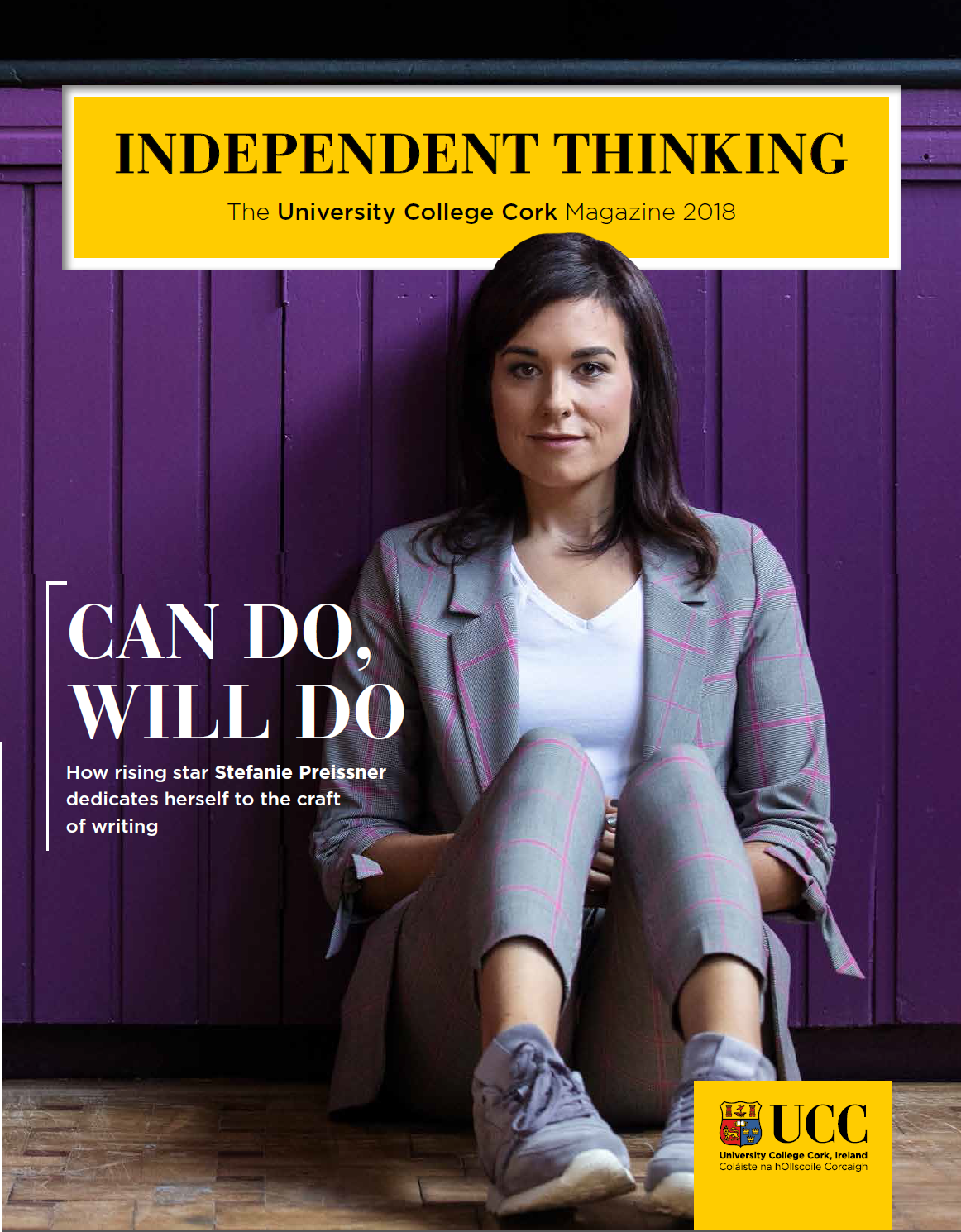

- Can Do, Will Do

Stefanie Preissner

- It’s not just a gut feeling

John Cryan & Ted Dinan

- Active citizen

Emily Duffy

- Leading the charge

Alan Hayes

- Gaeltacht adventures

Bliain Na Gaeilge

- Eachtraí sa Ghaeltacht

Bliain Na Gaeilge

- Don’t worry, bees happy

Fiona Edwards Murphy

- The times they are a-changin’

LGBT Staff Network

- Back to her roots

Maria Kirrane

- Shining a light

Mental Health in the Community

- Patrick’s call to nursing was no accident

Patrick Cotter

- A healthy separation, long overdue

Ivan Perry

- Woman of Steele

Susan Steele

It’s not just a gut feeling

UCC professors John Cryan and Ted Dinan, whose headlining scientific research has shown a link between bacteria in the gut and mood, tell Margaret Jennings that it’s all about diversity in the diet – so it’s OK to have the odd apple pie.

All guilt I’d felt at treating myself to a large scone slathered thickly with butter, before I met UCC professors John Cryan and Ted Dinan, dissolves not long into our conversation.

The two academics are superstars in the whole area of gut health, after their ground-breaking research proved that the trillions of bacteria living in our digestive system – the microbiota – can push through the brain barrier to affect our moods.

Having coined the phrase psychobiotics, they believe that soon doctors will be able to treat certain forms of depression and anxiety with good bacteria, or what will effectively be probiotics for the brain.

And they argue that lifestyle choices, in particular what we eat, as well as other factors like antibiotics, can have a huge influence on those microbes and in turn, our emotional state.

So that sugar-laden scone wasn’t doing too much damage to my microbes, it turns out, as long as I have a diverse healthy diet otherwise, says Ted, who is head of the psychiatry department, in addition to running a clinical practice at Cork University Hospital.

“I have a TERRIBLE sweet tooth – as John will tell you,” he says, smiling broadly in the direction of his research companion.

John, who is Chair of the Department of Anatomy and Neuroscience, has worked with him for over a decade, both of them Principal Investigators at the university’s APC Microbiome Ireland, where they have been funded by Science Foundation Ireland.

“I do keep it in reasonable moderation ... I mean, I did have a few small apple pies this morning ... in the middle of my clinic,” he laughs. “But apart from that, I would consider myself having a pretty healthy diet. The only way to maintain diversity in our microbiota is to maintain diversity in our diet. I mean, if the only thing I ate was pie, I wouldn’t have a very good microbiota!”

As a 10-mile-a-day runner, Ted is no doubt balancing his microbiota with healthy exercise as well, John points out.

“Like, Ted had multiple apple pies this morning and not a pick on him. If I had them I’m sure I would put on weight immediately,” he quips.

“When you throw in the influences of weight, metabolism and activity – like Ted will have a run, I won’t - there is an individual aspect, and we feel the microbiome is really precision medicine at its utmost, that it has the potential to be, that we can tailor what’s going on eventually.”

With almost 20 years in age between them – Ted, 63, and John, 45, they were both drawn together initially by their interest in stress and also Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) which is linked to anxiety and depression.

For sceptics who question how our microbes could affect our mood and behaviour, they might just need a good dose of food poisoning to convince them.

“No one has any problem with the realisation that if you get food poisoning, for instance, which is caused by a bacterium in your food – salmonella – it makes you sick and changes how you behave and how you feel,” says John. “So from an evolutionary perspective, why can’t the same pathways that are being used in these behaviour changes – driven by a microbe – be hijacked for positive effects, not just bad effects?”

What the UCC researchers – true examples of independent thinkers – have done is create that paradigm shift in thinking about mood and the treatment of mental illness, through what’s going on in the gut, and launched both themselves and the university onto the world stage.

Research they carried out for instance with some clinically depressed patients who were at the severe end of the spectrum, at Ted’s CUH clinic, showed they had less diversity in the microbiota in their gut than people who are not depressed.

“And then we did a transplant,” continues Ted. “And we looked at their microbiota, and it was definitely different to what you’d expect. We then gave rats, by faecal transplant, a humanised microbiota from healthy individuals and when that happened nothing changed; their behaviour was normal, their biochemistry normal and immunology normal.

“But lo and behold, we certainly didn’t anticipate it – when they got a transplant from the depressed patients, their behaviour became depressed like them.”

As is the case throughout our discussion, the two men rhythmically dip in and out of each other’s narratives, sharing the ebb and flow of their research journey.

So John adds: “Now the conundrum we have is: ‘What is that? What is driving it?’ What could it be?’ But it’s probably down to these molecules that these bacteria are making and that are driving it.”

Moving forward, one of their challenges is to “join all the dots up”, as John says. “We need to get at the pathways there in terms of neurotransmitters, different nerves, the immune system – find out which are at play and in what situations and how can we hijack them to actually produce things.

“And the second big question we have is in clinical translation. We want to get to a stage where we could do intervention studies in people with chronic illness. So we are quite excited.”

Their recent best-selling book The Psychobiotic Revolution, has reached an audience far beyond the world of scientific conferences where both men are in big demand.

It is an additional platform and an interesting title. “Yea,” says John. “With the book we really wanted to have a – no pun intended – digestible piece, backed by scientific rigour. We wanted to highlight this journey and where it’s going and it is a revolution – the beginning of a revolution.”

Neither would have guessed they would have been the flag-bearers for this revolution over a decade ago. With almost 20 years in age between them – Ted 63 and John 45, they were both drawn together initially by their interest in stress and also Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) which is linked to anxiety and depression.

It was in the 70s that Ted, then a medical student and a lover of motorbikes (still to this day), used to “ride out the straight road in Cork and look up at the big asylum there” and wonder about the large population of patients with schizophrenia within. That’s what drew him to his field.

We wanted to highlight this journey and where it’s going and it is a revolution – the beginning of a revolution.

John, who started out as a student of basic science and biology was “totally fascinated by the brain”. Now of course, he is working with the so-called “second brain” of the microbiome.

It’s been a wonderful journey for them, they both nod in agreement. And they’ve been accompanied on that journey by a bunch of colleagues who help make it all possible.

“Ted and I sit here every Friday with our APC colleagues and talk to these wonderful people who know nothing about the brain but they know a lot about the microbes, so we have this really interdisciplinary field.”

“Yes,” says Ted. “It is the multidisciplinary aspect of the whole thing that drives innovation. If you have people who are just in a single mindset, they are not going to make the same strides as people who are challenging you – coming from a completely different background.”

UCC should be really proud of the ability to put these people from different backgrounds together and in each of these fields to have success stories, they agree.

John and Ted’s book (with Scott C. Anderson), The Psychobiotic Revolution: Mood, Food and the New Science of the Gut-Brain Connection, is now available from all good bookshops. To find out more about their work, please visit www.psychobiotic-revolution.com.