News Posts

Icelandic Volcanoes and Irish Prehistory: tales of tephra

Icelandic Volcanoes and Irish Prehistory: tales of tephra

Ireland’s extensive peatlands have been accumulating for thousands of years, collecting and preserving material like pollen and plant fossils. Analysis of these remains, and the peat itself, provides us with a long term history of environmental change of the peatland and the local landscape, often showing us how humans were interacting with and shaping it. The further down you dig, the older this record gets.

Since the Neolithic period, humans have been utilising and crossing through Ireland’s peatlands, building wooden structures like trackways and platforms as they went. Over time these were swallowed by the rising surface of the peat bog and preserved in place, much like the pollen and other material.

Edercloon is a large complex of archaeological wooden structures, uncovered during road construction in Ireland. During the analysis of peat samples from the Edercloon excavations, archaeologists noted the presence of a microscopic layer of volcanic tephra. Tephra is any volcanic material that is ejected into the air during an eruption, and ranges in size from big blocks and bombs down to volcanic ash. The ash can be carried thousands of kilometres in the atmosphere, and is deposited all over the place, sometimes even in Ireland. It was infact ash from the eruption of the volcano Eyjafjallajökull is what brought European Airspace to a standstill in 2010.

The ash that was found at Ederloon had likely come from an eruption of the Icelandic volcano Hekla, in AD 1104. The ash travelled all the way from Iceland and was deposited on the bog surface nearly 1000 years ago, before being buried and preserved, much like the pollen and archaeology. As we know the year that this eruption occurred, the ash acts as a chronological marker or time-stamp within the peat.

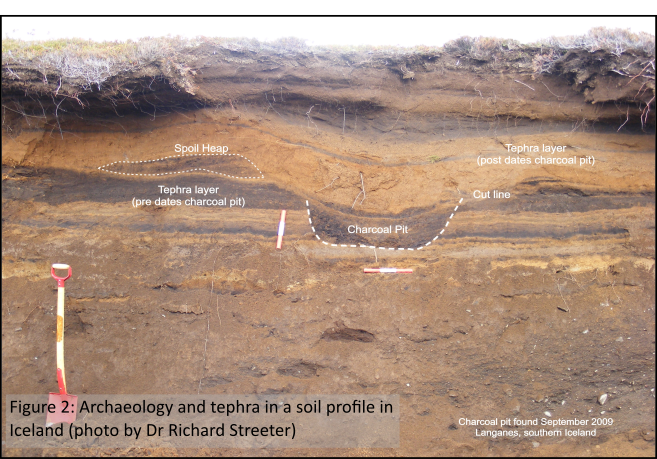

In Iceland, closer to the volcanoes, the tephra layers are much thicker, sometimes many metres thick. Over time, these tephra deposits are buried by soils and peat, so when you dig a hole in Iceland you may well find them preserved as distinct layers.

As Ireland is about 1400 km from Iceland, you’re unlikely to find any tephra layers thick enough to see there. However, if you process the soil just right, like they did at Edercloon, you may find microscopic shards of tephra that you can identify. There are a number of known Icelandic eruptions that have deposited ash in Ireland, and they are very useful to researchers for chronological and environmental analyses.

During my PhD fieldwork in northern Iceland, we found a 2 cm thick layer of that same Hekla 1104 AD tephra that was found at Edercloon, which is also found at archaeological sites in Iceland. We used this and other tephra layers to model how quickly the soil accumulated in the local area.

Icelandic archaeologists are very fortunate to have these tephra layers. Not long after humans settled Iceland around 872 AD, they started keeping very detailed written records which included the date of volcanic eruptions. The tephra from these eruptions are often found at archaeological sites and, once identified, provide clear chronological controls for human activity.

Unfortunately, microscopic shards of tephra are not always easy to find in Irish peat bogs, and even when they are, the eruption that produced them can’t necessarily be identified. Regardless, it is amazing to think that tephra from the same eruption fell on people and peatlands 1400 km apart. This is now preserved in the archaeological record connecting two different countries and cultures through time. Irish peatlands are an unparalleled resource of environmental and archaeological information, and tephra has a small but fascinating part to play in telling the story of Ireland’s history.

For more on this story contact:

Dr Lauren Shotter, IPeAAT Postdoctoral Research Assistant