UCC on RTÉ Brainstorm: Did humans have sex with Neanderthals?

Though humans and Neanderthals co-existed for no more than 20,000 years, there are tantalising scraps of evidence about the kinds of interactions they would have had.

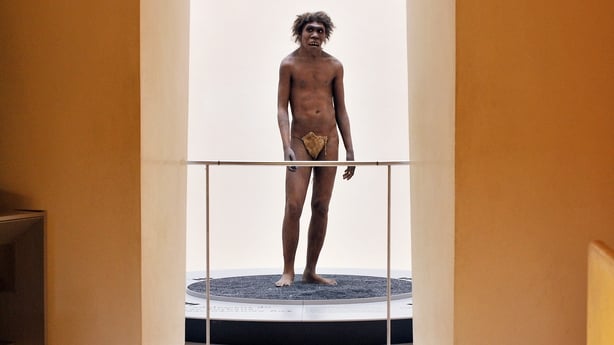

Our Neanderthal relatives first appeared in the fossil record approximately 400,000 years ago and disappeared about 30,000 years ago.

They evolved in Europe from an ancient hominin species called Homo erectus, which themselves arrived in Europe from Africa 600,000 years ago.

Neanderthal remains have been found throughout Europe, from western Spain to as far east as southern Siberia.

With their shorter limbs, barrel-shaped rib cage and large nose, they seem to have been built for short bursts of speed. Genetic evidence suggests that they may have had red hair and pale skin. The one thing we can be sure about is that there was sex

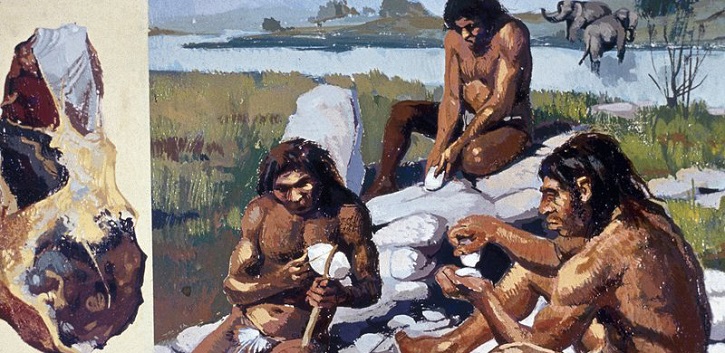

The stereotypical image of Neanderthals as knuckle-dragging oafs has changed in recent years.

Their brains were almost 20 percent larger than ours, they lived in caves, kindled fire, created cave art, used medicinal plants and had complex social structures that included burying their dead.

Climate change or competition from modern humans have been suggested as reasons for their extinction.

It is a common misconception that modern humans are direct descendants of Neanderthals; in fact, we are more like distant cousins.

We also evolved from Homo erectus, but we did so in eastern Africa about 200,000 years ago. We first left Africa for the Middle East 50,000 to 60,000 years ago, and it was here that our ancestors first encountered Neanderthals.

They co-existed for no more than 20,000 years – a blink of an eye in evolutionary time!

What were these encounters like? There are tantalising scraps of evidence suggesting that these interactions may have been more harmonious than would be expected given the constant struggle to survive in those ancient times.

The one thing we can be sure about is that there was sex.

This was first confirmed in 2010 when DNA from Neanderthal bones was sequenced and assembled into a complete genome, the full set of genetic instructions required to make a Neanderthal.

We may have taken an "evolutionary shortcut" by acquiring beneficial genes from Neanderthals

For the first time, scientists could compare the genome of a Neanderthal with the genomes of representatives from present day African, European, East Asian and Papuan populations.

As can be imagined, extracting and sequencing DNA from bones that have lain in the ground for tens of thousands of years is extremely challenging.

Such ancient DNA is highly fragmented and tends to contain large amounts of contaminating DNA from microbes and present-day humans.

However, advances in DNA sequencing technology allowed these short fragments to be sequenced with sufficient accuracy to assemble them into a complete genome sequence. Furthermore, handling the Neanderthal bones in the same way as evidence from a crime scene is handled has minimised the risk of contamination with DNA from the archaeologists and scientists who study them.

What have we learned from this information? One of the major findings is that about 2 percent of the genome of European, East Asian and Papuan individuals is inherited from Neanderthals.

This genetic exchange could only have occurred by interbreeding. In contrast, there is little to no Neanderthal ancestry in African populations.

This is unsurprising as Neanderthals were never present in Africa, and therefore Neanderthals and modern Africans did not have the opportunity to mix.

But neither were they present in China, yet similar amounts of Neanderthal DNA are found in East Asians and Europeans. This indicates that all non-African populations originated from that early migration from Africa into the Middle East nearly 60,000 years ago.

There, it is believed, they interbred with Neanderthals, and at some later point split and spread both west and eastwards to populate Europe, Asia, Melanesia and Australasia. Two Neanderthal gene variants have been linked to an increased risk of nicotine addiction

More recent work has found that another extinct hominin species, the Denisovans, interbred with the branch of modern humans that populated Melanesia, whose genomes have just under 5 percent Denisovan DNA, in addition to the 2 percent from Neanderthals.

Did we inherit anything useful from these encounters? Yes, is the answer.

When modern humans arrived in the Middle East and Europe they were confronted with new pathogens and climates.

It has been suggested that we took an "evolutionary shortcut" by acquiring beneficial genes from Neanderthals, who had over 200,000 years to adapt to life in these environments before we arrived.

The Neanderthal gene variants that are preserved in our genomes today were likely to have been advantageous in prehistoric times, but may not necessarily be beneficial today.

For example, one gene variant that we inherited from Neanderthals makes blood more sticky and likely to coagulate.

This would have been an advantage when injuries from hunting dangerous animals and haemorrhages due to birthing big-brained babies were more likely.

Morning Ireland: Listen to Dr John Murray discuss the commemoration of an Irish professor who coined the term Homo Neanderthalensis

But it could also increase the risk of blood clots and strokes now that people live much longer. Some other Neanderthal gene variants are found near our circadian, or "body clock", genes.

The products of these genes respond to sunlight and tell our body when to sleep, rise, and eat. These variants may have been useful adaptations for living in Europe, which has fewer daylight hours than Africa.

However, these DNA relics have been strongly associated with depression in Europeans today, perhaps because most of us now live under artificial light. Interactions between humans and Neanderthals may have been more harmonious than would be expected

Another Neanderthal variant, associated with reduced uptake of vitamin B1, has been linked to malnutrition. Vitamin B1, used in our gut to break down carbohydrates, would have been plentiful in diets rich in meat and nuts and until recently having the Neanderthal variant would not have been harmful.

But people eating processed foods today may not be getting enough of this vitamin. Interestingly, two Neanderthal gene variants have been linked to an increased risk of nicotine addiction.

It’s not all bad however, we have also inherited some Neanderthal genes that boost our immune system’s ability to fight infections from bacteria and fungi.

Thus, for better or worse, shadows of Neanderthal ancestry live on in many of us today.

By Dr Andrew Lindsay, Genetics, UCC. For more about courses in Genetics at UCC visit here

This article first appeared on RTÉ Brainstorm here

For more on this story contact:

Ruth Mc Donnell, Head of Media and PR, Office of Marketing and Communications, UCC Mob: 086-0468950