The Challenge of Achieving “Zero Hunger For All”

Famines are extreme events where people’s access to food is denied. The world had until recently almost abolished famines.

What the world is not even close to doing is abolishing hunger and malnutrition. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), about 815 million people in the world currently go hungry, in the sense of experiencing significant deficiencies in calorie intake; this number has increased recently. A much larger number, about one-third of the global population, experience malnutrition: two billion people have deficiencies in key micronutrients such as iron, zinc and vitamin A; a similar number of people worldwide are overweight or obese.

In 2015 the United Nations approved the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), seventeen ambitious goals to address key challenges and move towards sustainable, equitable global development. Ireland played a significant role in negotiating the SDGs, co-chairing with Kenya the process that brought them to final agreement. A key principle of the SDGs is to “leave no-one behind”. SDG 2 aims to end hunger and all forms of malnutrition by 2030, clearly a very ambitious aim. It seems unlikely that it will be achieved in that timeframe, but we can at least move in the right direction.

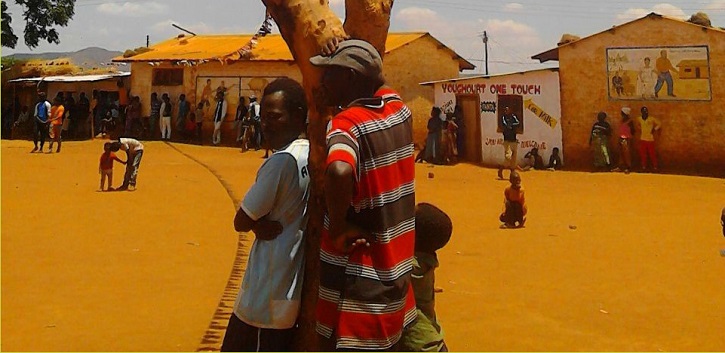

Some countries are already doing so. Take Ethiopia, a country which unfortunately became associated with famine in recent times as Ireland was in the more distant past. The politically-induced famine of 1984-85 in Ethiopia resulted in about 600,000 deaths and received huge media attention. Less well known has been the constant chronic food insecurity amongst many millions of households in Ethiopia struggling to produce enough food under poverty conditions of small landholdings, irregular rainfall, limited infrastructure and technology, and poor access to markets. Tackling these deficiencies is the focus of long-term development efforts in addition to the humanitarian work required to deal with specific food crises. Ethiopia has made considerable strides in the last two decades to overcome these deficits, mobilising internal resources as well as resources from external donor agencies including Irish Aid. Rapid economic growth and substantial public investment in agriculture, social services and infrastructure have resulted in rural poverty falling from 48% in 2000 to 26% in 2011; the real value of agricultural output increased by an average of about 9% per annum over that period and contributed to the reduction in poverty. A huge investment in social protection, the Productive Safety Net Programme, was introduced in 2005 and provides jobs, security and cash or food payments to up to eight million people in vulnerable rural households. Ethiopia has also developed a Rural Jobs Strategy with a major focus on enterprise and job creation for rural unemployed youth: a major challenge in a country where about one million new rural jobs need to be created every year to meet demand.

Many developing countries have not made the kind of progress seen in Ethiopia in recent years however. Protracted conflicts have exacerbated food insecurity in many countries, including Syria, Yemen, South Sudan, Somalia, Chad, northern Nigeria and Afghanistan: in 2017 about 124 million people across 51 countries faced crisis levels of food insecurity and both acute and chronic under-nutrition, where women and children are particularly affected. Resolving such conflicts is a difficult, necessary – but still not sufficient – requirement for dealing with food insecurity. Long-term climate change, bringing more frequent extreme weather events such as droughts which impact on agricultural production, is also contributing to food insecurity.

There are no magic bullets to achieve zero hunger for all, but there are many actions that can and need to be taken. A key requirement is investment on a large scale. It has been estimated that investing €1 in good nutrition can give a return of €16 due to improved life expectancy and productivity. Similarly investing €1 in preventing and mitigating natural disasters has been estimated to save €7 in humanitarian relief costs. Although there are many calls on global resources, investing in improving nutrition and livelihoods amongst today’s rural poor makes economic sense as well as being the right thing to do to ensure that no-one does get left behind.

But what kinds of investments are needed? There are many. Shenggen Fan, Director General of the International Food Policy Research Institute, states that there is scope for “sustainable intensification” within global food production systems such that increased food production is achieved with more efficient use of natural resource inputs (soil, water etc) while reducing environmental impacts. Development of drought-tolerant crop varieties, use of precision agriculture, conservation agriculture and drop irrigation are examples of technological developments which save land and water use while potentially increasing output. The authors of the 2017 Global Nutrition Report point to a range of actions which could simultaneously deliver a range of benefits across the SDGs. For example, promoting diversification of food production can provide multiple benefits, from contributing to healthier and more diverse diets and producing crops more beneficial to the environment, to supporting women’s empowerment through promotion of food-based enterprises while ensuring that time burdens are reduced. While improved food security requires increases in (the right kind of) agricultural production, improved nutrition requires actions across many sectors, including introduction of policies that promote good nutrition: this is a requirement in developed countries, faced with the growing problem of over-nutrition, as much as it is in countries which still suffer from the problems of under-nutrition.

Ireland has played, and can continue to play, a significant role in addressing the challenges of hunger and malnutrition. The memory of famine lingers on in Ireland and has contributed to the positive role played by Irish citizens, the Irish Government and Irish development organisations in responding to contemporary food crises. As important as it is to respond to the food crises which regularly hit the news headlines, we also need to be aware of the greater extent of chronic hunger and malnutrition which exists, less well noticed, but which is also an affront to our claims to be a just world. In the current Irish Government policy for International Development, “One World, One Future”, the Government made a commitment to invest 20% of the Irish Aid budget to address hunger. Now, as a new policy is being developed, it is important that the Irish Government continues to show international leadership in committing substantial resources, in collaboration with a range of stakeholders, to addressing the major global challenges of hunger and malnutrition and to ensuring that there is a positive move towards achieving the SDG goal of zero hunger for all.

Dr Nick Chisholm is Director of the Centre for Global Development at UCC and Senior Lecturer in International Development in the Department of Food Business and Development. He is the organiser of the conference on Global Hunger Today: Challenges and Solutions, supported by Irish Aid, which will be held in the UCC Boole 4 Lecture Theatre on 10th – 11th May. For further details see https://www.ucc.ie/en/cgd/globalhungertodayconference/.

Media: For further information contact Ruth Mc Donnell, Head of Media and PR, Office of Marketing and Communications, UCC Mob: 086-0468950