In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Disappeared but Still Remembered: Unearthing the IRA's Lost Victims

For the first time, Andy Bielenberg and Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc present a comprehensive list identifying most, if not all of those, ‘disappeared’ during the War of Independence.

This research features in an academic article “Shallow Graves – documenting & assessing IRA disappearances during the Irish revolution” which features in the current edition of The Journal of Small Wars and Insurgencies. The article is the first in-depth nationwide examination of this controversial aspect of the Irish struggle for independence and has broken new ground in detailing the full extent of these secret killings. The study is the result of several years of painstaking research in archives across Britain and Ireland examining thousands of contemporary accounts including police reports, British army files, IRA intelligence documents and the testimony of hundreds of veterans from both the IRA and British forces. The results of the research reveal that the disappearances by the IRA began during the War of Independence, starting in July 1920, and that at least 89 people were disappeared by republicans before that conflict ended.

Following the Anglo-Irish Truce in July 1921 the number of abductions and secret executions declined with just 16 such killings occurring. A further three such killings occurred during the Civil War. The largest category of those killed over the Irish revolution were 56 civilians suspected of spying or informing; British soldiers accounted for 30 and policemen for 20. Finally, two National Army soldiers were disappeared during the Civil War. The British forces for their part disappeared at least 7 victims at the time – the majority of whom were IRA Volunteers or civilians who had fallen foul of the RIC.

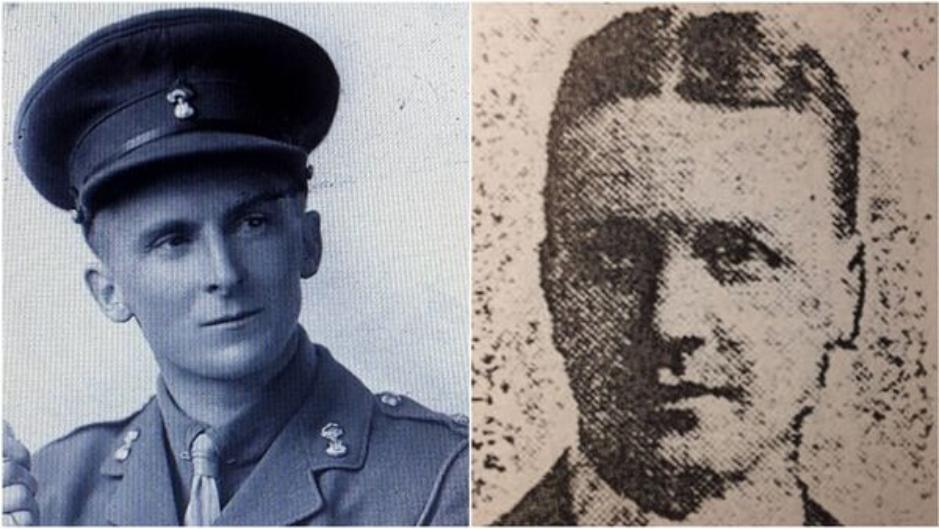

Left: Alan Ledrum, a Resident Magistrate who was disappeared by the Clare IRA in 1920; Right: District Inspector Gilbert Potter who was executed in Tipperary was the highest ranking member of the RIC to be disappeared.

There were several reasons why the IRA hid these executions. The most obvious is that hiding a body concealed evidence of the killing and made it difficult for British and later Free State courts to convict anyone for their involvement. The secret burial of executed British soldiers and RIC members taken prisoner also helped to prevent revenge attacks by their comrades in the British forces who were reluctant to strike in case the missing troops were being held hostage and might be executed in revenge for any reprisals. In some cases, the IRA’s tactic of hiding the bodies may have been retaliation for the refusal to release the bodies of republican prisoners who had been executed by the British army and who were instead buried inside barrack walls or in prison yards.

The most common method used by the IRA to dispose of the bodies was to bury them in bogs, forests or in remote mountainous areas. Occasionally bodies were hidden ‘in plain sight’ by secretly burying them in graveyards. In some cases, the remains of executed spies and Black & Tans were hidden in graves dug in family burial plots belonging to IRA Volunteers who had presided over their execution. Some IRA brigades, particularly those in the Midlands favoured disappearing their victims by disposing of them in rivers – but this appears to have been a relatively rare occurrence.

Although these executions happened a century ago the bodies of those disappeared are still being uncovered. The most recent recovery happened in May 2018 when the remains of Private George Chalmers were recovered from a bog in Clare. However, the majority of those disappeared during the Irish Revolution remain missing.

SPIES AND INFORMERS

The ‘intelligence war’ was undoubtedly one of the most important military aspects of the Irish War of Independence. For the British forces, the best way to defeat the republican insurgency was to acquire accurate intelligence information about IRA members and operations. The widespread closure of RIC barracks following IRA attacks and the success of Sinn Féin’s police boycott meant that from 1919 the British forces became increasingly dependent upon Irish civilians for information. To prevent this potential source of information Republicans inflicted a variety of punishments on those suspected of spying. Some received threatening notices, others were boycotted or were forced into exile – in the most extreme cases the penalty was death.

The majority of those killed by the IRA as spies were shot and their bodies were deposited in public places with a “spy notice” affixed to their corpse as a warning to others. The labelling and display of these corpses was an imitation of British military practices during the First World War and was an attempt at convincing the public that the IRA was a disciplined body bound by bureaucratic and judicial processes. In May 1920 IRA headquarters began issuing a series of ‘General Orders’ in an attempt to regulate the military conduct of local IRA units who were executing spies. Officially, the death sentences passed on all suspected spies had to be approved by the local IRA Brigade Commandant and reported to the Adjutant General of the IRA in Dublin. The reality however is that lower ranking IRA officers often sanctioned executions without waiting for formal approval.

Edward Parsons, an alleged spy executed by the IRA during the Truce and buried on the Kinsale Road.

Close to two hundred civilians alleged to be spies or informers for the British were killed by the IRA during the War of Independence; 42 of these were disappeared by the IRA. Another three civilians were disappeared for reasons unrelated to the intelligence war. The secret interrogation and execution of alleged British spies created confusion and panic within British spy networks and this was exploited by the IRA as a way to expose other informers.

Jerome Davin, Commandant of the IRA’s 3rd Tipperary Brigade in recalling his role in the disappearance of one spy stated:

Speaking of spies, I never agreed with the policy of labelling them after execution and leaving their bodies on the roadside. That policy embarrassed the people who lived in the houses near where the bodies lay and perhaps resulted in reprisals being carried out on those people. I preferred to have the spy buried quietly and leave an air of mystery about his fate.

WOMEN

A recurring problem for the IRA was the fraternisation of Irish women with members of the British forces. Many of these women, especially those who entered into personal relationships with members of the British army or RIC, were suspected of spying. The IRA had a range of punishments for women they deemed collaborators. The most common penalty these women suffered was the public humiliation of having their hair cropped.

Maria Lyndsay one of the few women who was executed by the IRA.

In 1921 IRA headquarters issued general order which stated that women found guilty of spying were to be forced into exile. However local IRA commanders sometimes took more extreme measures and at least three women who had been accused of spying were executed by the IRA. Of these killings the case which achieved greatest notoriety was that of Maria Lindsay, a wealthy Protestant Loyalist who lived at Leemount House, Coachford. Lindsay was abducted with her chauffeur, James Clarke. Her case was raised in the British House of Commons where it was admitted that she had conveyed information on an IRA ambush to crown forces. This had resulted in the capture and imprisonment of several of the would be IRA ambushers including five who were later executed. Lindsay and Clarke were then arrested and held as hostages in an attempt to prevent the executions of the captured republicans but were executed in March 1921 after the British proceeded with the execution of the IRA prisoners.

In the same month another Cork woman; Bridget Noble, suffered a similar fate on the Beara peninsula. The IRA claimed that Noble had been seen frequenting Castletownbere RIC Barracks and meeting with the local RIC Sergeant. Noble was punished by having her hair shorn. She reported this assault to the British authorities and wrote letters to the local RIC garrison identifying the members of the IRA responsible. Her house was subsequently raided by the local IRA company and when her correspondence with the police was discovered Noble was abducted and held prisoner for a period, tried as a spy and executed.

In the cases of both Lindsay and Nolan IRA regulations prohibiting the execution of women were ignored, revealing an aberrant and ruthless streak within the Cork IRA. The secret executions of Brigid Noble, Maria Lindsay and other suspected female spies and informers may have occurred because the IRA felt that the execution of women would lose them public support if news of these became known. Alternatively, these ‘disappearances’ may simply have been a means of protecting the IRA volunteers involved from prosecution by hiding evidence of the killings.

SECTARIANISM?

There is a marked difference between the number of Protestant suspected spies disappeared nationwide compared to the number of similar killings in Cork. Outside of Cork, there were only 2 of the 19 civilians disappeared who have been identified as Protestants, which largely undermines any potential sectarian explanations. In County Cork in contrast, 11 of the 37 disappeared IRA victims, approximately 30% were Protestant. This looks significant when compared to the 10% Protestant share of the population of County Cork.

The Protestants disappeared by the Cork IRA in 1920 were all suspected of involvement with a Loyalist network dubbed ‘the anti-Sinn Féin Society’. Whilst Maria Lindsay and her chauffer James Clarke had been involved in warning the British of a planned IRA ambush an action that resulted in the deaths of several IRA Volunteers. The Protestants disappeared by the IRA during the Truce included the first three killed during the Dunmanway Massacre of April 1922, as a reprisal for the shooting of an IRA volunteer who broke into the house of the victims. The remaining 2 Protestants disappeared in the Spring of 1922 – Thomas Roycroft had recently been discharged from the RIC whilst Edward Parsons was a suspected spy.

Whilst Cork Protestants were certainly over-represented among those disappeared as suspected spies and informers killed in Cork, the number of documented cases are still fairly small in the wider context of fatalities during the conflict at large. Furthermore, Protestants were targeted for the most part for their suspected or active Loyalist opposition rather than their religious denomination and the significance of these killings has been somewhat exaggerated on the supposition that there was an underlying sectarian motive to these killings, an interpretation advanced as a propaganda tactic on the British side at the time. Nonetheless, the killing of relatively greater numbers of suspected loyalist spies and informers, including those who were not disappeared, combined with other disturbances, fear and regime change were sufficiently unsettling for the Protestant community to contribute to the factors increasing their emigration out of Cork to relatively higher levels than in other parts of Ireland.

MISSING BRITISH SOLDIERS

British soldiers captured by the IRA were also likely to face execution and secret burial and a total of 25 British soldiers were disappeared during the War of Independence.

The first British soldier to be executed by the IRA was Private George Robertson who was captured with Lance-Corporal Alexander McPherson near Connolly, Co. Clare on October 28, 1920. The pair claimed to be deserters and were initially treated favourably. However, McPherson escaped after gathering information about his captors and returned to the area the following day leading British search parties directly to each location in which he had been held captive. Following McPherson’s escape the IRA executed Robertson and buried him in Ballynoe Bog.

Previously British deserters were regarded as a valuable source of arms and intelligence. After Robertson’s execution the IRA became increasingly wary of supposed deserters. At least ten British deserters were executed – the majority of them being disappeared. Several previously anonymous soldiers disappeared by the IRA have now been identified by cross referencing IRA reports with lists of deserters compiled by the British army. For example, Lieutenant Denis O’Dwyer of the 6th Battalion 1st Cork Brigade recalled in his memoirs that: “Early in 1921, a British soldier in uniform without badges was caught in the locality. He stated he was a deserter. He gave no name or regiment.

We were very suspicious of him for many of the alleged deserters were spies. It was eventually decided to execute him and I was one of the party detailed for the job. … His remains were buried on a farm about a mile from Grenagh village. As far as I know, his remains are still there.

British records show that this soldier was Private R.G. Brown who deserted at Donoughmore on 13 January 1921.

Two unidentified members of the Machine Gun Corps who were captured by the IRA near Charleville apparently admitted they were gathering intelligence before they were executed and secretly buried. Their bodies were reinterred in the 1950’s with a Commonwealth War Grave headstone inscribed: ‘Two soldiers of the Great War known unto God’. The pair have now been identified as Private’s Cagney and Musgrove who had deserted from their base at Kilmallock in May 1921.

Major Geoffrey Compton Smith who was disappeared by the IRA in 1921. His body was recovered in 1926

Many of the executed British soldiers were not deserters but British officers captured alone roaming the countryside. The IRA unsurprisingly assumed they were on intelligence-gathering operations. The first two killed were Lieutenant’s Bernard Brown and Daniel Rutherford who left their barracks in Fermoy dressed in civilian clothing. When captured by the IRA they were carrying camping gear and were equipped with a camera. The IRA suspected the pair were on an intelligence gathering mission and they were executed and buried in the Rusheen district. A fortnight later, the Cork IRA disappeared another three British officers; Captains Green, Chambers and Lieutenant Watts who were bundled off a train at Waterfall. The trio had previously been identified as intelligence officers by IRA agents inside Victoria Barracks, Cork, but this was denied by the British army subsequently; in a number of instances they subsequently admitted an intelligence role of victims killed by the IRA.

Perhaps the best known of these missing British officers was Major Compton-Smith of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers whose disappearance drew significant press interest at the time. Smith was held hostage against a group of IRA prisoners who scheduled for execution on 28 April 1921 and when those executions were carried out he was killed in reprisal and buried in a shallow grave. His remains were later recovered and buried at Fort Carlisle in Cork Harbour.

The Missing Policemen Civilians disappeared by the IRA were usually carefully targeted because they were suspected of being spies and their abduction and execution were carefully planned in advance. By contrast, the execution of captured members of the RIC was usually more opportunistic with the bodies of those killed being hastily concealed.

RIC MEMBERS

Unlike other categories of victims the disappearance of members of the RIC was rare in Cork and was most likely to occur outside the county. A total of 19 members of the force were disappeared by the IRA during the War of Independence. A handful of former members of the RIC were the subject of forced disappearances during the Truce period.

The first members of the force to be captured and secretly executed by the IRA were RIC Constable Patrick Waters and Ernest Bright, an English Black and Tan. The pair who were stationed in Tralee and were abducted in a spur of the moment IRA operation in October 1920. There were persistent rumours that Waters and Bright had been killed by being thrown alive into the furnace of the Tralee Gas Works which incinerated their bodies – in fact both men had been shot dead and buried in a remote area of the Sliabhmish Mountains where their bodies remain today.

Leonard French an RIC Auxiliary killed in Kilkenny. The IRA hid his body to prevent British reprisals.

The highest ranking member of the RIC to be disappeared was District Inspector Gilbert Potter who was taken prisoner at the Hyland’s Cross Ambush in April 1921. Potter was held hostage while the IRA offered to exchange him for IRA volunteer, Thomas Traynor, who was in a British prison in Dublin awaiting execution. Following Traynor’s hanging Potter was shot and buried in the Comeragh Mountains.

Aside from Constable Waters and DI Potter the disappearance of members of the regular RIC was relatively rare and captured Black and Tans and members of the RIC Auxiliary Division were more likely to suffer this fate.

Following the Scramogue Ambush in Roscommon in March 1921 the IRA captured three British soldiers who were treated humanely. However, the two English Black & Tans captured were shown no mercy. Constable Robert Buchannon was immediately shot dead and his body was dumped in the River Shannon.

Constable Jim Evans was kept alive for a short period by his captors who needed him to train them in how to operate the Hotchkiss machine gun that had been captured in the ambush. Once this task was achieved the IRA executed Evans and buried him in a nearby bog.

EXAGGERATED CLAIMS ABOUT DISAPPEARANCES IN EAST CORK

There has been considerable speculation on the scale of IRA disappearances at Knockraha east of Cork city following claims made by Martin Corry an IRA veteran from the area. Corry later served as a Fianna Fáil TD representing the East Cork constituency for several decades. Throughout his political career Corry spoke quite openly about his alleged role in numerous IRA executions and disappearances. In IRA Brigade Activity Reports he claimed that 27 people had been disappeared by his unit (The Knockraha Company) in East Cork. As the years went by Corry inflated this figure and by the 1970s he claimed that around 35 people had been executed by his men, including some victims who were buried on his own farm at Glounthane near Cork.

Taoiseach Eamon de Valera with Martin Corry TD (right) who boasted of his involvement in secret IRA executions

Corry was prone to exaggeration and even claimed to have taken part in numerous killings for which there is no historical evidence. Futhermore, Corry claimed to have presided over verified executions such as that of Edward Parsons, in which he had no role. Many of these stories were gross exaggerations. For example, Corry claimed that his IRA unit had disappeared 17 British soldiers from the Cameron Highlanders regiment. This is impossible since British records indicate that only three soldiers from that regiment went missing in Cork during the entire period.

Corry also claimed that Edward Maloney, a fellow IRA veteran who held prisoners at a vault at Kilquane graveyard, kept careful records of 60 prisoners held there, 35 of whom Corry alleged were executed and secretly buried. However Maloney contradicted this and stated that he was unsure of how many people had been held prisoner there. In short, Corry’s testimony needs to be handled more critically by historians and it seems sensible at this point to treat his assertions with at least some degree of scepticism.

While some disappearances throughout Ireland remain undocumented (including a few at and around Knockraha), a number of claims with regard to disappearing victims were also bogus.

THE TRUCE PERIOD AND CIVIL WAR

The Anglo-Irish Truce of 11 July 1921 brought a formal end to the War of Independence and after the ceasefire the number of forces disappearances and secret executions by the IRA declined dramatically, except in County Cork, where they continued but at a somewhat lower level.

Many of the disappearances which occurred in breach of the ceasefire related to suspected spies who has escaped the IRA during the War of Independence.

The first to be disappeared during the Truce was James Devoy, an ex-soldier who was employed at Ballincollig Barracks. Devoy was abducted on suspicion of spying and was never seen again.

Thomas Hanley, an ex-soldier from Newcastle West, County Limerick joined the RIC Auxiliary Division and served as an ‘identifier’ pointing out the homes of local republicans to British raiding parties and identifying captured republican suspects. After Hanley retired from the RIC he was tracked to his home where he survived being shot five times in a failed IRA assassination attempt. After the attack Hanley made preparations to emigrate to America but before he could do so he was abducted by the IRA in October 1921 and taken to Macroom where he was executed and buried in secret.

Richard Mulcahy had been IRA Chief of Staff during the War of Independence when most of the secret executions and disappearances occurred.

Edward Parsons a suspected informer for the British forces was abducted by armed IRA volunteers who were waiting near his home at Number 30, High Street, Cork on the night of the March 23, 1922. According to IRA accounts, Parsons was armed with two revolvers when captured. Parsons had previously been questioned by the IRA in late 1920 and was alleged to have admitted his role as an informer when he was observed shadowing a senior IRA officer in the city. Parsons was executed by shooting four days later and was buried between Lehenagh and Ballygarvan on the Kinsale Road.

Several disappearances are associated with one the most controversial episodes of the Irish revolution. At Ballygroman house in April 1922, an IRA commandant was fatally shot whilst breaking entry at night, seemingly to secure the use of a car. The armed denizens refused access and defended the house until they ran out of ammunition. The next morning, Thomas Hornibrook, his son Samuel, and Herbert Woods surrendered to the IRA and were subsequently executed and buried in Farranthomas Bog, Newcestown. This marked the beginning of a host of additional fatal attacks on Protestant Loyalists in the Bandon valley, known as the ‘Dunmanway Massacre’. Events at Ballygroman appear to have given rise to a reconnaissance mission to the town of Macroom, by three British army intelligence officers, Lieutenants Hendy, Dove, Henderson and their driver, Private Brookes, who were captured by the IRA, executed and buried in secret.

After Cork, Tipperary was the county where the IRA disappeared most spies during the Truce. Late in 1921, Jerry O’Brien, who appears to have been a member of the Travelling Community, was abducted by the IRA near Upperchurch and executed for spying. The second Tipperary case was William Dillon. All of the male members of the Dillon family had been suspected of spying during the War of Independence. The first attempt to shoot him during an IRA raid on the family home went catastrophically wrong and resulted in the accidental killing of Dillon’s younger sister. The IRA returned in May 1922 and captured William Dillion who was executed and buried at Tollomain Castle.

During the Civil War (1922-23), IRA disappearances became negligible and those targeted were different than in the preceding years. They include two National army soldiers; Lieutenants Cruise and Kennedy, captured together near Clonmel, County Tipperary, whose bodies were buried in a ditch four months later.

Though at least fifteen suspected civilian spies were executed by the IRA during the Civil War only one civilian victim, William Frazer, a loyalist publican from Newtown, County Armagh was disappeared on 30 June 1922. There remains some uncertainty about the motive for his abduction and execution. Frazer was a former member of the UVF, an Orangeman and a B-Special. He had previously shot a member of an IRA raiding party seeking arms. That he disappeared soon after a spate of IRA reprisals targeting Protestant Loyalists known as the Altnaveigh massacre, implies there may have been a link. It was the only disappearance carried out by the IRA in the six counties which became Northern Ireland during the Irish revolution.

County Cork in contrast, accounted for 65 of the 108 documented disappearances to date, accounting for far more disappearances than the rest of the country combined. But this must be placed in the wider context of the total numbers killed in Cork during the Irish revolution (over 800 people) and in particular the intensity of both the IRA campaign and British counter insurgency operations in the county during the final year of the War of Independence when most disappearances occurred.

RECOVERING THE BODIES

The Duke of Devonshire contacted the Free State Government in 1923 seeking the return of the bodies of British soldiers disappeared by the IRA.

Following the end of hostilities in the Civil War, Victor Cavendish the British Secretary of State for the Colonies wrote to the former IRA leader Richard Mulcahy, who was then Chief of Staff of the Free State Army in an attempt to retrieve the remains of British soldiers who had been disappeared by the IRA during the War of Independence. About the same time the families of the disappeared approached the government of the Irish Free State seeking the return of their relatives remains. Initially, these inquiries met with limited success beyond receiving confirmation that the missing person had been executed by the IRA. But thereafter greater efforts were made and the bodies of 30 of the disappeared were recovered between 1921 and 1927 after local investigations carried out with the assistance of IRA veterans.

Discoveries continued in the following decades with the bodies of the Herbert Woods and the Hornibrooks being recovered by Gardaí and reburied in a Church of Ireland cemetery. In the 1950s the remains of the two Charleville ‘deserters’ Privates Cagney and Musgrove were accidentally discovered by a local former and given a formal Christian burial. The occasional recovery of those disappeared in the War of Independence continues up to the present day. The skeleton of Patrick Joyce, a school teacher who served as an informer for the RIC was discovered buried a Galway bog in 1998. The most recent recovery occurred in 2018 when the remains of Private George Chalmers a British soldier who had been executed in 1921 were unearthed in Clare.

To date, the bodies of 38 of those who were disappeared by the IRA between 1920 and 1923 have been recovered but the remains of at least 70 others who met the same fate are still missing.

There are no confirmed cases of disappearances in Cork during Civil War.

| The Disappeared in Cork during the War of Independence | |

|---|---|

| 10 July 1920 | John Crowley, Ballymurphy, Bandon. |

| July 1920 | James O’Gorman, The Rea. |

| 15 Aug 1920 | John Coughlan – Aghada. |

| 20 Aug 1920 | James Herlihy, – Pouladuff, Cork city. |

| 15 Sept 1920 | John (Sean) O’Callaghan Jr – Farmers Cross. |

| 29 Oct 1920 | Lieut Daniel Rutherford – Rusheen. |

| 29 Oct 1920 | Lieut Bernard Brown – Rusheen. |

| 6 Nov 1920 | RIC Constable Thomas Joseph Walsh, Blarney. |

| 15 Nov 1920 | Captain Montague Green – Waterfall, Aherlea. |

| 15 Nov 1920 | Captain Stewart Chambers – Waterfall, Aherlea. |

| 15 Nov 1920 | Lieutenant William Watts – Waterfall, Aherlea. |

| 16 Nov 1920 | Cadet Bertram Agnew – The Rea. |

| 16 Nov 1920 | Cadet Lionel Mitchel – The Rea. |

| 23 Nov 1920 | Thomas Downing – The Rea. |

| 28 Nov 1920 | Cadet Cecil Guthrie – Annahalla Bog, Macroom. |

| 29 Nov 1920 | James Blemens – Carroll’s Bog, Cork City. |

| 29 Nov 1920 | Frederick Blemens – Carroll’s Bog, Cork City. |

| 3 Dec 1920 | Private Percy Taylor – Kilbree, Clonakilty. |

| 3 Dec 1920 | Private Thomas Watling , Kilbree, Clonakilty |

| 9 Dec 1920 | George Horgan – Lakelands, Blackrock-Mahon. |

| 13 Jan 1921 | Pte RG Brown, Grenagh. |

| 20 Jan 1921 | Dan Lucey, Kilcorney, Milstreet. |

| 21 Jan 1921 | Daniel Lynch, Killeady Quarry, Ballinhassig. |

| 23 Jan 1921 | Patrick Ray, Church Hill, Passage. |

| 20 Feb 1921 | Private Albert Mason – Ballincollig. |

| 20 Feb 1921 | Private B. Pincher – Ballincollig. |

| 4 March 1921 | Brigid Noble – Eyeries. |

| 12 March 1921 | David Nagle, Clashanure, Ovens. |

| Mid-March 1921 | Maria Lindsay – Donaghmore. |

| Mid-March 1921 | James Clarke – Donaghmore. |

| 1 April 1921 | Pte F. Roughley – Ovens. |

| 11 April 1921 | Michael O’Brien –Cork City. |

| 28 April 1921 | Major George Compton Smith, Donoughmore. |

| 30 April 1921 | Arthur Harrison – Coachford. |

| 5 May 1921 | James Saunders – Dunbolloge. |

| 16 May 1921 | David Walsh, Doon, Glenville. |

| 19 May 1921 | Francis McMahon, Ballyphehane. |

| 23 May 1921 | Private Walter Musgrove– Charleville. |

| 23 May 1921 | Private P. J. Cagney – Charleville. |

| 23 May 1921 | William McCarthy – Mourneabbey. |

| 24 May 1921 | Lieut Seymore Vincent, Lenihans bog, Glenville. |

| 29 May 1921 | John Sullivan-Lynch, Carrigrohane. |

| 5 June 1921 | Private Matthew Carson, – Ovens. |

| 5 June 1921 | Private Charles Chapman – Ovens. |

| 5 June 1921 | Private John Cooper – Ovens. |

| 5 June 1921 | Eugene Swanton, The Rea. |

| 8 June 1921 | John Joseph Walsh. – Ahanesk, Midleton. |

| 19 June 1921 | Leo Corby, -Killathy graveyard, Ballyhooly. |

| 24 June 1921 | Pte George Caen, Ballincollig. |

| 11 July 1921 | William Nolan, Cork city. |

| 11 July 1921 | John H. N. Begley – Douglas, Cork city. |

| Truce Period Mid-July | James Devoy, Killbawn, Co. Cork. |

| 12 Aug 1921 | Patrick Cronin –Dunmanway. |

| 17 Oct 1921 | Thomas Hanley. Macroom. |

| 26 Oct 1921 | Lance Corporal J. Anderson, Glounthuane. |

| 9 Mar 1922 | Thomas Roycroft, Cork city. |

| 23 March 1922 | Edward Parsons. Kinsale Road, Cork. |

| 26 April 1922 | Lieutenant Ronald Hendy, – Macroom. |

| 26 April 1922 | Lieutenant George Dove – Macroom. |

| 26 April 1922 | Kenneth R Henderson – Macroom. |

| 26 April 1922 | Private J R Brooks – Macroom. |

| 26 April 1922 | Herbert Woods – Farranthomas, Newceston. |

| 26 April 1922 | Samuel Hornibrook, Farranthomas, Newceston. |

| 20 June 1922 | Michael Williams Sunville, Glounthuane |

| There are no confirmed cases of disappearances in Cork during Civil War. |

|

Learn more about the 'disappeared' of the War of Independence in the Cork Fatality Register

This article was first published in the Irish Examiner on 13 September 2020