In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Dr Donal Ó Drisceoil looks at how the Brigade Activity Reports from the Military Service Pensions Collection shed light on the nature of the IRA at war, particularly in County Cork, the ‘storm centre’ of the Irish war of independence.

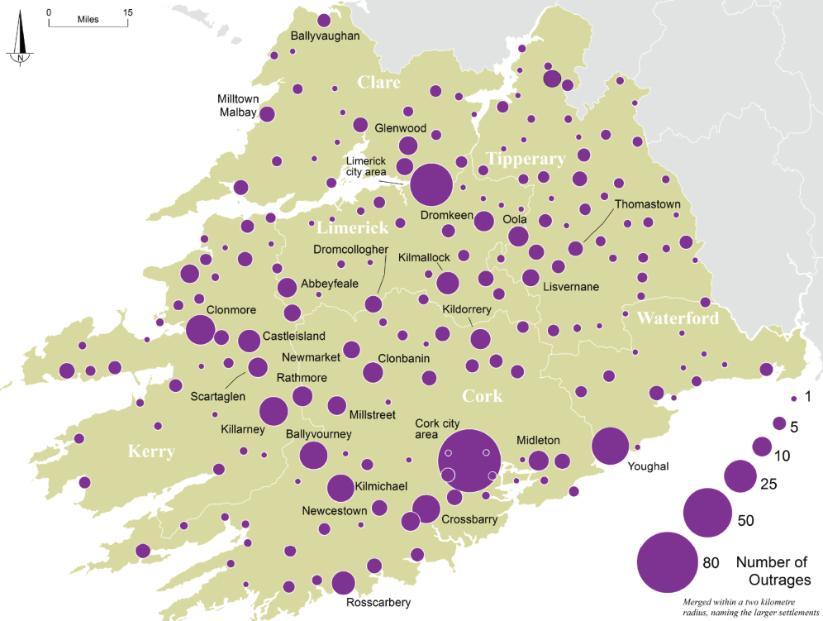

County Cork was the storm centre of the Irish War of independence. The Military Service Pensions Collection (MSPC) Brigade Activity Reports from IRA units across the country were made available to the public in 2019 and in terms of the sheer volume of activities recorded, the Cork reports confirm the county’s centrality to the conflict. The reports were prepared by Old IRA Associations to provide background information to aid assessors in making decisions on granting pensions to veterans of the war of independence.

The activities list from one of the more active West Cork companies (companies were the smallest units of the IRA) shows a level of sustained activity that almost matches that for the whole of neighbouring County Waterford. The material relating to the other highly active counties in the Munster ‘war zone’ – Tipperary, Clare and Limerick – likewise confirms existing knowledge about these areas.

The most active IRA brigades in the country – those in West Cork (Cork No. 3) and North Cork (Cork No. 2/Cork No. 4) – provide the most comprehensive and compelling reports. The North Cork reports are the most streamlined and focused, which echoes in some ways the record of the IRA in this area during the war of independence. In a cover document, it claimed that ‘for every engagement brought off, there were at least three attempts made. Considering the number of engagements which are reported, it will be realised that this Brigade was one of the most active Brigades in Ireland’, which indeed it was. Given the high level of self-regard that comes through in this report, it is not surprising that these were the men who posed for Sean Keating’s iconic painting, Men of the South.

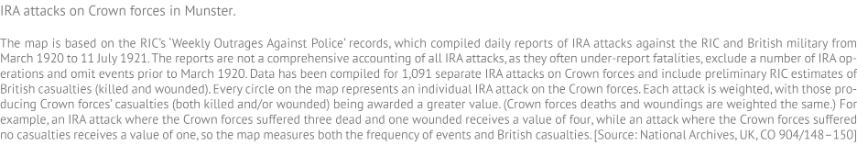

An example of the maps of its operations provided by the North Cork IRA.

There were often significant delays in making returns, in Cork as elsewhere, and this doubtless influenced the fate of applications of many veterans in those areas, whose claims lacked the verification required. The city-centre-based B Company of the 2nd Battalion, Cork No. 1 explained in a cover note that ‘the geographical position of the [company’s] area, (a peninsula adjacent to R.I.C. HQ at Union Quay) and the type of people who mainly inhabit it made military activities extremely difficult. The area was inhabited mainly by wealthy merchants of Cork City who were, generally speaking, hostile . . .’.

H Company of the 1st Battalion, based in the western suburbs and outskirts of the city, explained that its lack of ‘qualifying operations’ arose from the absence of military and police posts and its area was used mainly as a ‘get-away district, and for the removal of spies, prisoners, etc.’.

The Kilmeen Company of the 1st Battalion, Cork No. 3 specialised in bomb-making, and explained that ‘owing to the work in the bomb factory men from the Coy. were prevented from taking part in major engagements.’

The Ballinspittle Company of the 1st Battalion, Cork No. 3 in West Cork had a more direct explanation for its lack of successful operations – it was discovered late in the day that a Second Lieutenant of the company was ‘giving the game away’.

The advocacy of the claims of those companies and individuals whose main activity was of the ‘supportive’ kind is a constant theme in the reports and yields fascinating insights into the ‘non-spectacular’ activities of most IRA volunteers. The North Cork battalions emphasised repeatedly the roles of those such as engineers, ‘who, while they may not have been actually concerned in any engagement, should have as good a claim to full-time military service as the men actually attached to the columns.’

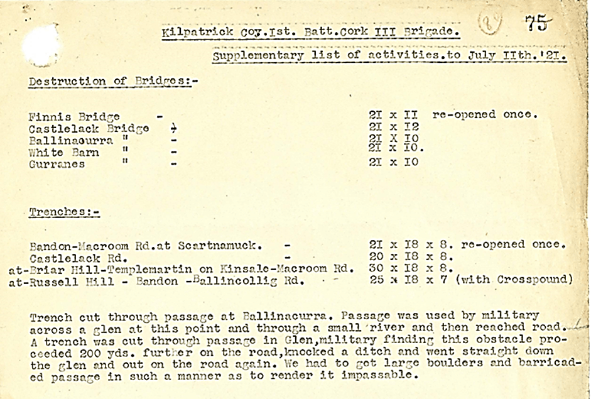

Most West Cork companies supplied lists outlining activities such as road trenching and the destruction of bridges, which became the dominant activity for most in the first half of 1921 as the IRA set out to destroy the transport network. This laborious and dangerous work was mainly done at night. Transport had to be commandeered and whole companies were mobilised to provide scouting, signalling, armed protection and carting. The risks were highlighted in February 1921 when trenchers from the Kilbrittain Company were surprised by Crown forces at Crushnalanav Cross and four were killed.

Details of Bridge Destruction and Road Trenching activities provided by the Kilpatrick Company

Railways were another crucial battleground in the conflict. Most of the IRA members employed by the Great Southern & Western Railway Company at Glanmire railway station were members of A Company, 1st Battalion, Cork No. 1. This company area was a particularly ‘hostile’ one from an IRA perspective, including as it did Victoria Military Barracks, King Street, St. Luke’s and Lower Road RIC stations, and Empress Place, HQ of the Auxiliary Division of the RIC. There were strong interconnections between local businesses and families and the Crown forces and according to volunteer Seán Healy the area was ‘infested with British spies and informers and only for taking drastic action against these people we could never have survived.’

The shooting of suspected spies and informers is a controversial issue in relation to the Cork IRA; over a third of all civilians executed by the IRA across the country were killed in Cork, and the Cork No. 1 Brigade area accounted for the vast majority. The Brigade Activity Files do not shy away from these executions and provide details not just of the executioners, but those who identified them, kidnapped them, drivers, armed guards, lookouts, and those who disposed of the bodies.

Fascinating detail is supplied on the level of support and back-up by nearby companies for the Tom Barry’s flying column before and after the Kilmichael ambush of November 1920. The Ballinacarriga Company guarded the column in the company area for two days and three nights after the ambush, while five members of the company took part in the ambush itself. The demands placed on companies by the flying column is everywhere evident. The same Ballinacarriga company was mobilised in full, for example, to relieve the column when it was surrounded following a failed ambush, but the column managed to escape. This highlighted the danger posed by the concentration of forces into one large column. The North Cork IRA used the less risky strategy of smaller columns attached to each of its battalions, which came together and broke up again very quickly.

Companies right across the West Cork region were frequently burdened with the responsibility of billeting Tom Barry’s large column and providing guards, sentries, scouts, guides and transport. The members of Clubhouse Company were probably less-than-delighted to find Barry’s seventy-strong column waiting to be fed, watered and protected when they returned to base at daybreak following a long-night’s road trenching in March 1921. The column was preparing for the famously successful attack on Rosscarbery RIC barracks, which many had thought to be impregnable.

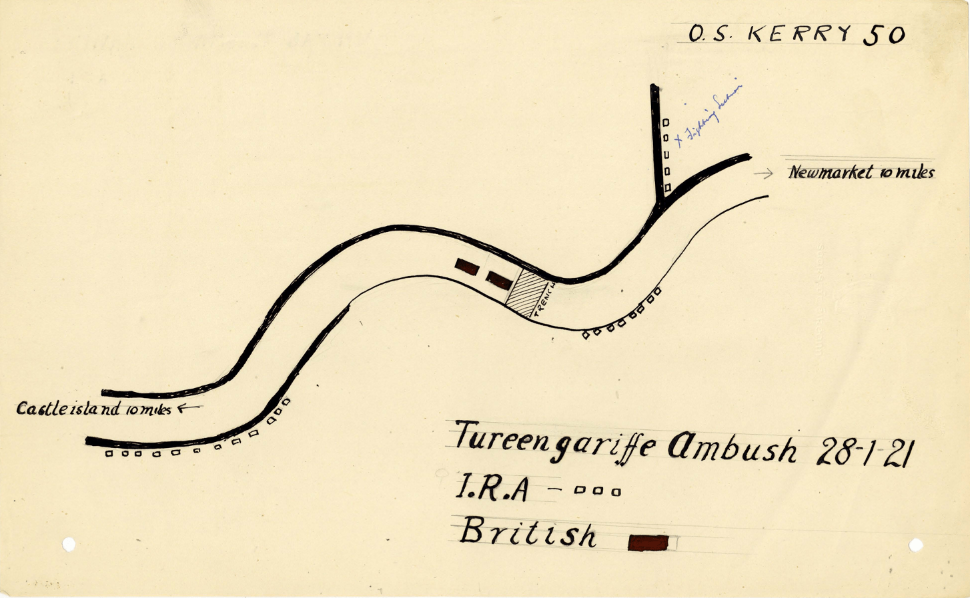

Rosscarberry barracks was one of the dozen barracks that had remained open into 1921 in West Cork (nineteen others had been abandoned under IRA pressure). The IRA’s countrywide offensive against RIC stations had begun in Cork in January 1920, and by early 1921 65 per cent of those in the county had been abandoned. Some barrack attacks entailed a huge mobilisation, as indicated in these reports in relation to the Blarney Barracks attack of June 1920. While only thirty men were involved in the attack itself, several hundred are listed as being on duty that night ensuring that reinforcements were blocked from coming to the rescue. This involved felling trees and creating other obstructions on all approach roads, cutting wires and launching diversionary attacks.

The ready availability of this material brings us closer to creating a definitive historical- geographical overview of the Irish revolution. For those with a more local focus, more names can be attached to particular events, and located in particular places at specific times. The Brigade Activity Reports, together with the other wide range of sources available on the Irish Military Archives website, enhance both the ground-level view and the broader perspective, which will feed off each other in what is promising to be an exciting phase of research that will lay the basis for a new revolutionary history.

The Brigade Activity Reports are available atwww.militaryarchives.ie.

– This article by Donal Ó Drisceoil was first published in the Irish Examiner on 2 January 2021-