Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

by John O'Callaghan

The opening phase of the Civil War, from late June to mid-August 1922, was characterised by large-scale, fixed-position confrontations between the National Army and the IRA. The National Army won these contests for territory because it had superior resources, including better logistics and heavier weaponry. The IRA’s belated recourse to exclusively hit-and-run guerilla tactics allowed it to fight on until May 1923.

The battle for Limerick city

The battle for Limerick city started on 11 July 1922. A week of sniping, running street battles and dramatic but ineffective raids by armoured cars on fortified positions resulted in stalemate. When a National Army 18-pounder field gun entered the fray, however, swiftly reducing its first target, republicans realised that their strongholds were no longer defensible. The retreating IRA burned barracks. Sgéal Chatha Luimnighe [Limerick War News], published by the National Army, reported that ‘all night [20-21 July] the city was illuminated by the flames … The destruction is enormous’. During the ten-day battle locals looted food, thousands evacuated, commerce ground to a halt, and there was no rail service or mail. The only newspapers were propaganda sheets. There was significant infrastructural damage, with private citizens and businesses large and small suffering losses.

The battle for Kilmallock

Republicans made their next stand around Kilmallock, the first big town between Limerick city and the Cork border. Kilmallock and its hinterland presented a barrier to a National Army advance on Cork and a threat to the flank of an advance westwards to Kerry. The IRA’s 1,500 well-armed, high calibre troops initially outnumbered the National Army in south Limerick, but republican morale was low after a series of defeats and reinforcements swelled National Army ranks to 2,000 by early August. Crucially, the National Army opened a second front to the rear of the ‘Munster Republic’ when troops landed from the sea near Tralee on 2 August. This played on local loyalties and the Kerry IRA men in Kilmallock returned home, prioritising the defence of the ‘Kingdom’. The Cork contingent anticipated the southern coastal attack that would come the following week and also slipped away. The National Army eventually marched into Kilmallock, unopposed, on 5 August.

The battle for Kilmallock marked a juncture in the war, between the decisive fare of late June, July and early August, and the drawn-out guerrilla phase. By mid-August, the National Army held every significant population centre in north Munster, along with Cork city. The majority of the killing was done in the opening seven weeks of the war.

As the fighting evolved into lingering, excruciating republican insurgency and National Army counter-insurgency campaigns, most of the remaining casualties were inflicted before the end of 1922. From late 1922 constant arrests and weapons seizures by Free State forces around the country, and to an extent the terrorising effect of executions and other State violence, made it increasingly difficult for the IRA to mount meaningful military operations.

There was no sustained guerrilla campaign in Limerick for a number of reasons: firstly, the withdrawal of the Cork and Kerry IRA units, who had done much of the fighting in the county, back to their home areas; secondly, the large National Army garrison in the city and around the county; and lastly, the fact that IRA units from Limerick drifted into other counties, one highly effective column operating primarily across the border in Tipperary for instance.

-832x548.jpg)

Fig. 1 Map showing the location and affiliation of the 98 combatant and civilian fatalities in County Limerick between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923

New Research on Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

Andy Bielenberg and John Dorney’s new database of Civil War fatalities, 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923, documents ninety-eight deaths in Limerick, the first on 10 July 1922, the last on 19 April 1923. Of these victims, forty-three were members of the National Army, twenty-nine were civilians and twenty-six were republicans (twenty-four IRA, one Cumann na mBan and one member of Na Fianna). Along with the Cumann na mBan member who died, seven of the civilians were women. Among the forty-three National Army dead, seven were former members of the IRA, one was a former member of Na Fianna, four were ex-British army servicemen and one had served in the Canadian army.

Chronology

Almost sixty per cent of the deaths in Limerick happened in July-August 1922, thirty-eight in July and twenty in August. This was the period of the battles for the city and Kilmallock and the most intense fighting in the towns of west Limerick. The National Army suffered eighteen losses in July, four in August and five in September. Civilians deaths numbered thirteen, five and three in those months. Most revealingly perhaps, IRA deaths went from seven in July and eleven in August to none in September. A pattern of vindictive reprisals and tit-for-tat killings, judicial and extra-judicial, scarred winter 1922-spring 1923. The worst atrocities occurred where the guerrilla campaign was most determined. So, while Tipperary, Cork and Kerry saw intensified conflict, in Limerick there were few deaths in combat after early August 1922 and fewer cold-blooded killings. After eighty-four deaths in Limerick in 1922, there were only fourteen in 1923 (seven National Army, three civilians, four IRA). The last IRA man killed in action in Limerick was shot in early December, only halfway through the war. Most of the seven National Army deaths in 1923 resulted from accidents.

Deaths in each category

Civil War fatalities were concentrated in or close to the major urban centres on, mainly Belfast, Dublin, and Cork. Limerick conforms to this pattern. Including accidents, the exchanges in Limerick’s densely-populated city centre from 11-21 July fatally wounded as many civilians (eleven) as combatants (seven National Army, three IRA and one Na Fianna). Approximately a dozen of the twenty-nine civilians killed over the course of the war were caught in crossfire or otherwise injured in fighting between the belligerents. Accidents claimed six civilian lives, three in incidents involving National Army motor vehicles and three in National Army shootings, including one man who died when a drunk soldier’s weapon went off in a city pub. Another civilian was fatally shot by the National Army while apparently trying to escape from custody. State forces, namely the Crown forces during the War of Independence and the National Army during the Civil War, frequently cited attempts to evade arrest or escape custody as reasons for shootings that occurred in murky circumstances.

Wanton National Army indiscipline was often whitewashed but there were instances in which the State pursued the truth, such as Joseph Butler’s killing of Michael McSweeney in Patrickswell in August 1922. Butler, in uniform and carrying a rifle, was drinking with a group (including the victim) in a village pub. He shot McSweeney after a dispute and a murder trial was held in the Central Criminal Court in 1924. Given previously friendly relations between Butler and McSweeney, the role of alcohol, and the lack of a clear motive, the shooting appeared to have been spontaneous. So, while Butler was found guilty and sentenced to hang, the jury recommended mercy and the judge agreed. Butler spent more than five years in prison for his gross indulgence of the power conferred upon him by his weapon.

A danger to themselves

The National Army lost eighteen men in Limerick in July 1922 alone. The highest monthly total thereafter was five in September. While more than half of the National Army’s forty-three casualties were killed in action, more than a third died in accidental shootings, some of them self-inflicted and some caused by unskilled or careless colleagues. Hastily trained and deployed, novice National Army soldiers were often more of a danger to themselves and each other than to the enemy. General Eoin O’Duffy claimed that many recruits who arrived in Limerick from the Curragh had never handled a rifle.

Daniel O’Neill shot himself while drinking tea and ‘toying’ with his revolver in a friend’s city home in July 1922. His family’s claim for a Military Service Pension was denied because Daniel’s death was ‘due to serious negligence and misconduct on his part’. Daniel’s brother James, a civilian, had been killed by Crown forces in 1920. In another typical case of incompetence and misfortune, in early 1923 twenty-year-old Sergeant-Major John Ryan was killed by his comrade Private Howell in Coolbawn barracks, Castleconnell. Howell was cleaning his rifle on the ground floor when a bullet went through the ceiling, striking Ryan, who was in bed on the first floor.

The IRA had fewer guns than the National Army and IRA men were usually more experienced than their National Army counterparts, hence only one of their number died in the type of accidental shooting that claimed so many pro-Treaty lives. Half of the IRA’s twenty-four casualties were killed in action.

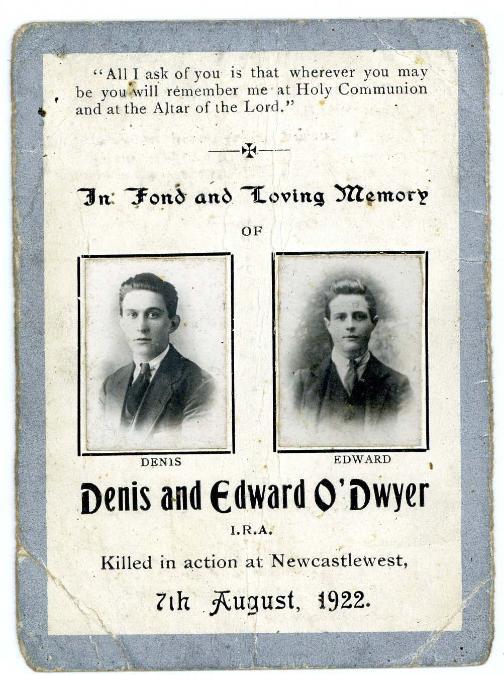

The Free State executed two IRA men in Limerick prison in January 1923 and it seems that that National Army committed a number of extra-judicial killings: two IRA men were shot in custody and three were shot while allegedly attempting to escape from custody or evade arrest. Volunteers Edward and Denis O’Dwyer, brothers from Limerick city, were killed in Newcastlewest in early August 1922. Edward was ‘killed in action’ but according to their sister Annie O’Dwyer’s Military Service Pension application, Denis ‘was taken prisoner and then brutally murdered … he was put against a wall and his body was riddled by machine-gun fire’.

Fatality Profiles

Civilians: James Ambrose and Daniel King

On 16 October 1922, in the townland of Ballyquirke, a couple of miles south of Newcastlewest, two civilians named James Ambrose and Daniel King were shot and killed. Ambrose was a farmer from Killeedy Cross. King was a labourer from nearby Ballykenny. Both men were in their early forties and married with families. Ambrose’s wife, Sally, was pregnant with their eigth child. Daniel and Catherine King had six children, the youngest of whom was not yet two-years-old. As they travelled home that night from Newcastlewest in a pony and cart, there may or may not have been a call of ‘halt’ before two shots were discharged from the side of the road. The medical testimony at the inquest was that Ambrose and King were hit by a single .303 calibre round. The bullet went through Ambrose’s thigh before piercing both of King’s thighs. They died due to ‘shock and haemorrhage greatly assisted by want of attention’. The verdict of the inquest was that Ambrose and King’s injuries were ‘inflicted by some person or persons unknown’. The Lee Enfield rifle, a formidable weapon that could fire a projectile more than 1.5 miles, used .303 ammunition. There were tens of thousands of Lee Enfields in Ireland in October 1922, the vast majority in pro-Treaty hands. National Army patrols seventy-strong had been in the locality, and there were reports of troops drinking nearby. Furthermore, witnesses testified that a number of troops were in the area at the time of the shooting.

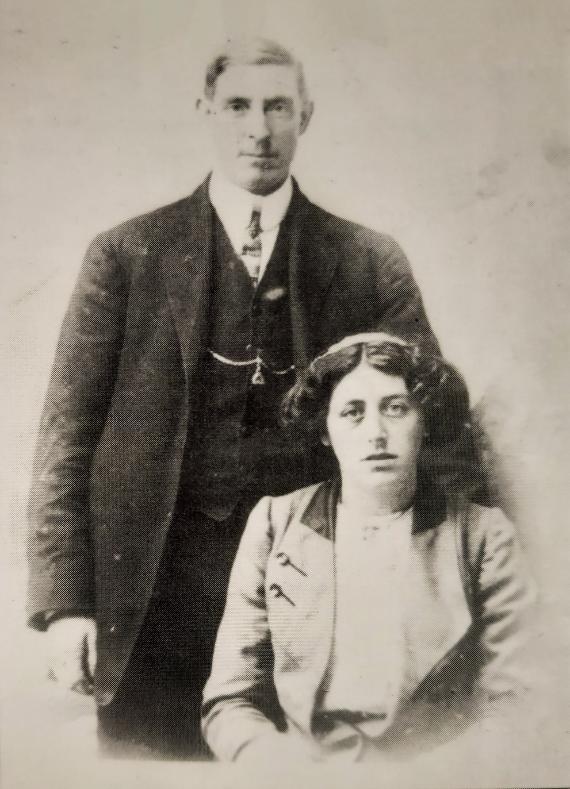

Fig 2. Farmer, James Ambrose, and his wife, Sally, who was pregnant with their eight child when he was killed by the National Army. [Courtesy Liam O’Mahony, grandson of James and Sally]

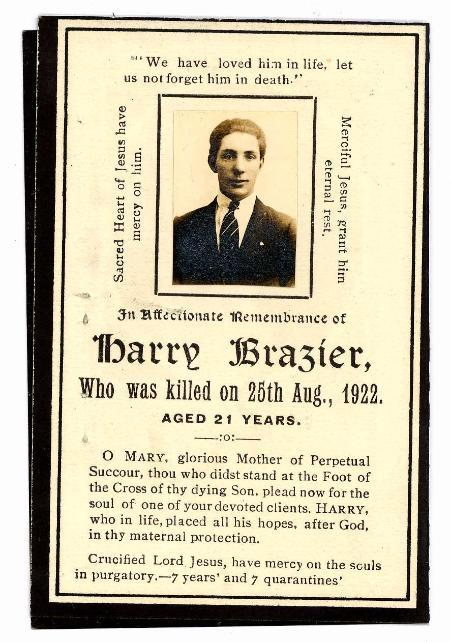

IRA: Harry Brazier

A veteran of the War of Independence, twenty-year-old IRA man Harry Brazier was from Edward Street in Limerick city. He worked as a mill-hand in a timber yard before joining the Great Southern and Western Railway company as a cleaner. He was an acting fireman when the National Army shot him dead at the railway works on 25 August 1922, allegedly after he had attacked an officer and was attempting to evade arrest. There does not seem to have been an inquest into his death, which went unregistered. This explains why Harry’s father, Walter, substituted a memorial card in place of a death certificate when applying to the Army Pensions Board for financial support in 1933. He also included a photograph of Harry’s headstone and anniversary notices from newspapers. In 1936, after much wrangling between the Departments of Defence and Finance, Walter was awarded a gratuity of £50 (sterling) because Harry had contributed financially to the family, who were therefore partially dependent on him.

Fig 3. Memorial card for Harry Brazier, IRA, submitted by his father as part of his successful dependant’s allowance claim. Harry was killed by the National Army in Limerick city on 25 August 1922 while trying to avoid arrest. [Courtesy of the Military Archives]

National Army: Joseph Hanrahan

Like Harry Brazier, National Army Lieutenant Joseph Hanrahan was a Limerick city man, a veteran of the War of Independence and a Great Southern and Western Railway employee. From Reeve’s Path, Upper Mallow Street, Hanrahan worked as a wagon builder. On 17 October 1922, he was shot at close range while out walking with friends. There were entrance and exit wounds to his back and abdomen, and his intestines were perforated. He died on 23 October of peritonitis. The attending physician, Dr James Roberts, condemned the ambulance that transported Hanrahan to hospital as a disgrace to the city and likened it to a manure cart. IRA men Gerald ‘Eberty’ Fitzgibbon and Joseph ‘Energy’ O’Connor were convicted of Harrington’s killing and sentenced to death and fifteen years imprisonment respectively. According to witnesses, Hanrahan was able to address his killer after being shot: ‘oh Eberty, you have got me’. Hanrahan and Fitzgibbon had been members of the same IRA unit; E Company, Mid Limerick Brigade.

Fitzgibbon and O’Connor escaped from Frederick Street barracks on Christmas Eve. In early 1925, in an application for compensation to the Army Pensions Board, Hanrahan’s frustrated father expressed his resentment of the amnesty announced by the Free State in late 1924: ‘he lost his life in assisting to establish law and order, while today walking the streets of Limerick, the men that were tried and convicted for his death are as free as the air, well clothed and fed and not interfered with by the established forces of Saorstát Éireann’.

Fig. 4 Memorial card for Denis and Edward O’Dwyer, IRA, submitted as part of their siblings’ unsuccessful dependant’s allowance claims. Denis and Edward both died in Newcastlewest on 7 August 1922. Edward was killed in action. Denis was shot in National Army custody. [Courtesy of the Military Archives]

Author’s Bio

Dr John O'Callaghan SFHEA, Teaching and Learning Centre, ATU Sligo, has published widely on the history of the Irish Revolution.