National Army Fatalities

National Army Fatalities of the Irish Civil War

Jack Kavanagh

The list of fatalities compiled for the UCC Irish Civil War Fatalities project encompasses the IRA, civilians, members of the crown forces, the National Army, and other pro-Treaty state forces such as the Civic Guard, Criminal Investigations Department (CID) and Citizen Defence Forces (CDF). The timeline of fatalities runs from 28 June 1922 to 24 May 1923. During this period there were 648 pro-Treaty fatalities out of a total of 1,426 civil-war related deaths in the twenty-six counties. With 637 fatalities, (compared to 426 IRA and 336 civilians), the National Army suffered the greatest losses. There are few sites of commemoration dedicated to these soldiers, apart from large-scale memorials such as the National Army plot at Dublin’s Glasnevin cemetery, where the centrepiece is the large gravestone of Michael Collins. Attempts to study recruitment to the pro-Treaty military, and those who died within it, are at an embryonic stage within the broader historiography.

Consistent Low Intensity Losses

Some isolated incidents involving ambushes and/or explosive trap mines, particularly in August, September and October 1922, yielded unusually high National Army fatalities of ten or more in a single day. More generally, between the outbreak of Civil War in June 1922 and the ceasefire in May 1923, the government forces suffered consistent low-intensity losses. The cumulative effect of low-intensity losses meant that 472 soldiers had died by 31 December 1922. When compared (albeit problematically) to the Finnish Civil War, which resulted in over 35,000 deaths within a few months, these losses are minimal (Kissane, 2020). A more useful point of comparison in the Irish context, are the 491 Irish paramilitary fatalities between 1917-21 listed by Eunan O'Halpin and Daithí Ó Corráin in The Dead of the Irish Revolution (2020). In the first five months of civil war, National Army fatalities were approximately 95 per cent of total Irish losses during the previous two years of guerrilla warfare.

Geography of National Army Fatalities

A National Army soldier’s experience of the Irish Civil War was a mixture of street-to-street urban fighting, suppression of guerrilla units in remote rural areas and infrequent fixed battles such as engagements in the Bruree-Bruff-Kilmallock triangle in County Limerick in July 1922. The Civil War is often broken down into ‘conventional’ and ‘guerilla’ stages to differentiate the types of tactics and strategies used by the opposing forces. The reality on the ground, however, tended to reflect local circumstances and whether the National Army had managed to clear a city or town sufficiently to establish a garrison. The highest numbers of National Army fatalities occurred in Cork (107), Kerry (88) and Dublin (94). Mayo was the only county in Connacht with significant National Army losses (45), reflecting the uneven nature of sustained opposition to the pro-Treaty forces.

With some exceptions, the National Army retained the initiative throughout the conflict. This helps explain the relative consistency of the fatality rate as the military was typically advancing on or defending territory it had already won. All National Army manoeuvres and tactics were based on a straightforward objective: to consolidate territory for the Provisional Government. Anti-Treaty IRA tactics and strategy were far more malleable and often shaped by local contexts. Fighting against the Treaty was the unifying principle – (a universally understood alternative was never proposed) - and activity waxed and waned depending on the locality.

.jpg)

Fig. 1 Map of National Army fatalities in the thirty-two counties between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923

Social Profile

The social profile of the National Army is difficult to reconstruct from the available archival records. The Irish Army Census taken in mid-November 1922 provides a ‘snapshot’ of the burgeoning army, but it is missing key information such as prior occupation and levels of educational attainment. The UCC project has determined prior occupation for the majority (530) of the 637 National Army fatalities, and this can be used as a proximate for the wider military, with the caveat it is a very small sample. Comparing the UCC dataset to the overall age profile and home address of each recruit recorded in the Army Census demonstrates that the UCC data is largely representative of the National Army in November 1922. (Table 1).

| Table 1: National Army Age Profile |

|---|

| Age Profile | Census | % of Total | Fatalities | % |

| 1-14 | 15 | 0.05 | 0 | 0 |

| 15-19 | 6,886 | 22.7 | 96 | 19.8 |

| 20-24 | 13,042 | 43.1 | 206 | 42.7 |

| 25-34 | 7,740 | 25.6 | 150 | 31.1 |

| 35-44 | 2,058 | 6.8 | 23 | 4.8 |

| 45-54 | 496 | 1.6 | 7 | 1.4 |

| 55-64 | 55 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 |

| 65-75 | 1 | 0.003 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 30,293 | 482 |

Table 1. National Army Age Profile: Irish Army Census November 1922 & UCC Fatalities Project. The totals for the Irish Army Census are taken from a fully transcribed data set undertaken as part of the author’s PhD research. Recruits and fatalities with missing age data are not included in this table

In both sources, the highest numbers recorded are in the 20-24 and 25-35 age ranges. The latter, slightly older age profile suggests that many of those soldiers would have held some form of employment or trade prior to joining the National Army. According to the UCC data for National Army fatalities, the three highest categories of employment were unskilled labourers (190), skilled workers (78) and unskilled agricultural labourers (74). A minority were employed as professionals (10), students (2) and business owners (1). In terms of geography, the National Army at the time of the Irish Army Census contained a plurality of Dublin-based recruits, although there was a considerable presence of rural recruits. Taking the five largest counties of origin and comparing them to the UCC fatalities project revealed a very similar trend (Table 2). Ranked from highest to lowest, the table shows that, apart from counties Clare and Limerick, the home counties of recruits and casualties follow very similar patterns. Clare ranks higher on the casualties list and Limerick is better represented on the recruitment list.

| Table 2: National Army County of Origin |

|---|

| County | Census | County | Fatalities | |

| 1st | Dublin | 7,008 | Dublin | 152 |

| 2nd | Cork | 2,754 | Cork | 59 |

| 3rd | Limerick | 1,735 | Clare | 37 |

| 4th | Tipperary | 1,532 | Tipperary | 32 |

| 5th | Galway | 1,321 | Glaway | 31 |

| Total | 14,350 | Total | 311 |

Table 2. National Army Origin County: Irish Army Census November 1922 & UCC Fatalities Project. The total size of the National Army as recorded by the Irish Army Census was 31,469. Only the five largest counties that were listed as home counties by National Army personnel are listed in this table.

The sheer size of the National Army and the lack of comprehensive personnel records has led to a series of claims about the overall character of the military. A common assumption is that the National Army had a disproportionate number of British ex-servicemen within its ranks. While the true numbers of soldiers with some form of prior military service will likely remain unknown, the number of National Army casualties with prior para/military service has been established, where possible, in the UCC Civil War fatalities project. Of the 637 fatalities, 150 had prior service within the IRA, 105 had prior service with the crown forces, eight were former members of Fianna Éireann and there was a single ex-Canadian Army serviceman. There were also seven casualties who had dual service in both the IRA and British forces, which raises questions about whether a substantial number of ex-servicemen serving in the National Army had prior service with the IRA or pre-split Irish Volunteers.

Causes of Death

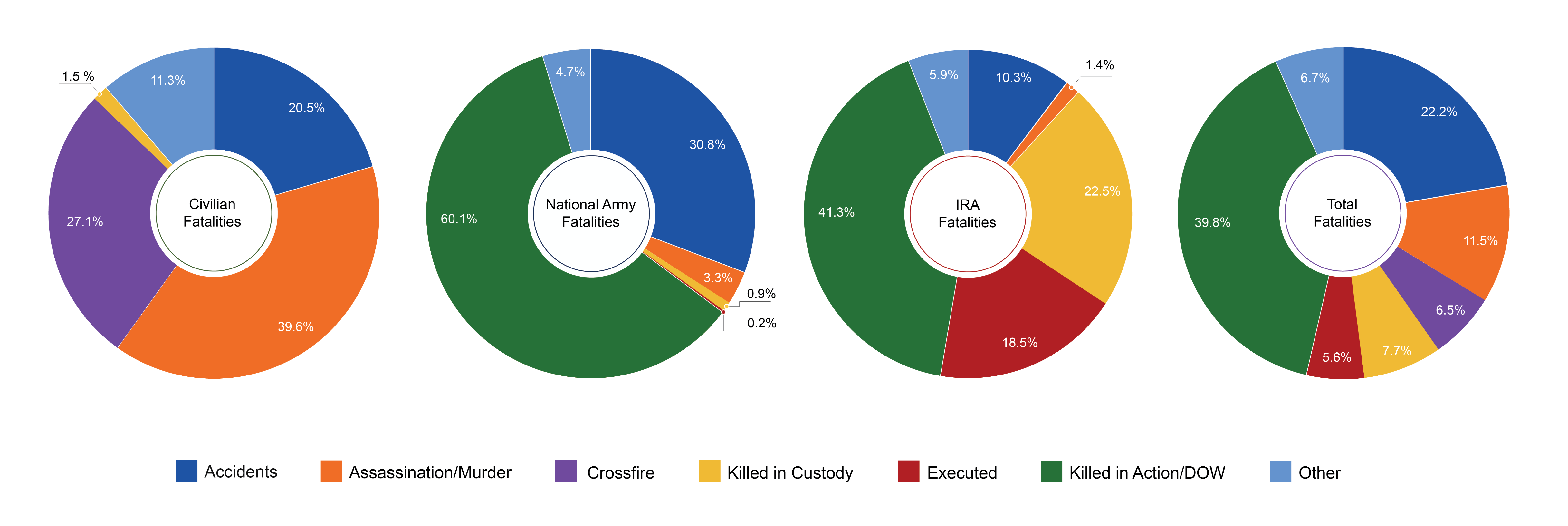

Based on the data collected for the UCC project, the majority of the 637 National Army fatalities were killed in action, assassinated, or shot (392). The most violent counties for National Army combat deaths were Cork, Kerry, Dublin, and Tipperary. The second most significant cause of death was accidents of various kinds (197). These deaths were concentrated in Dublin, Cork, Kerry and Limerick. Explosions killed thirty-five soldiers, most of whom died in County Cork. The remaining fatalities were as a result of illness (9), murder (3) and a single execution (1).

In contrast to the complex picture of National Army fatalities, IRA men were typically killed in combat or executed by the state. This discrepancy can be largely explained by the difference in scale between the two forces. The National Army reached a strength 48,176 officers and men by March 1923 (MA/HS/A/0876), and was occupying over 400 distinct posts and barracks across the Free State. It is estimated that the National Army reached a total strength of 60,000 officers and men before the start of large-scale demobilisation in 1923-4. In contrast, the number of active IRA personnel was closer to 12,000 at the outset of the conflict (Hopkinson, 2004). The large number of garrisons utilised by the National Army likely played a significant role in the number of accidental deaths in its ranks, allowing for more incidents of ‘horseplay’ involving firearms. A culture of indiscipline involving alcohol was likely another contributing factor.

Fig 2. Pie charts showing cause of death in each category in the twenty-six counties between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923

Fighting for a Free State

When the Irish Free State was formally established on 6 December 1922, the new government had asserted a tentative control over its twenty-six-county territory. The National Army had established garrisons in every county and controlled the three largest population centres: Dublin, Cork and Limerick. Significant challenges remained in rural hinterlands where the authority of the new state largely existed on paper. The tactical decision of the IRA to return to guerrilla-style warfare after August 1922 had exacerbated a key problem for the National Army leadership. Like the British administration from 1919-21, they were facing an asymmetric opponent who did not need to win outright, only successfully convince the general public that the new state was incapable of establishing a baseline of normalcy (Valiulis, 1992).

In the immediate post-Civil War atmosphere of political anti-militarism and a determination by the Free State government to remove the military from a place of national prominence, details of the National Army fatalities and their dependents were largely obscured. The erection of a ‘Cenotaph’ in the grounds of Leinster House was effectively an exercise in myth making and the focus on Michael Collins, Arthur Griffith and Kevin O’Higgins emphasised the overtly political nature and martyr style aesthetic of the monument.

During the actual conflict, there were attempts by the National Army to catalogue and monitor the levels of fatalities. While these figures are estimates, it is important to note that the National Army leadership was alive to the reality of high casualties and how this would affect morale. Due to the high numbers of recruits that flowed into the military after the issuing of the ‘Call to Arms’ in early July 1922, the recruitment to casualty ratio was negligible and had no practical effect upon the ability of the military to perform its core function. Psychologically, however, the consistent casualties clearly played a key role in the decision by certain army units and commanders to engage in ‘unofficial’ or extrajudicial killings which were a notable feature of the Irish Civil War.

Fig. 3 The National Army Plot at Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin [Image: John Crowley]

Fatality Profiles

28 June 1922: Colonel-Commandant Thomas Arthur Mandeville of 21 Lower Pembroke Street, Dublin, a civil engineer who joined the National Army in 1922 (Irish Independent, 1922), was travelling in a motor car with a party of soldiers and Captain Michael Vaughan when they were fired upon in Leeson Street. The wounded Mandeville was brought to St. Vincent’s Hospital where he subsequently died from wounds (Irish Times, 1922). Vaughan also died from gunshot wounds received. These two soldiers were among the first casualties of the Irish Civil War.

10 April 1923: Corporal Elmer Loftus, of 10 Parton Street, Belfast, Co. Antrim was killed in New Ross Barracks, Wexford. According to a summary of a subsequent military court of inquiry, around midnight on 9 April 1923, Corporal Loftus dressed in civilian attire had attempted to ‘test’ the alertness of the sentries at the barracks. Loftus successfully surprised the first sentry, Volunteer Gaffney and took his rifle. A second sentry, Volunteer Harpur hearing calls for aid, immediately shot Loftus. Before dying of his wounds, he commended the sentries for remaining alert. Loftus had served in the British Army towards the end of the First World War, after which he returned to Belfast. He joined the National Army on 12 July 1922 at the Curragh Camp and was appointed a corporal (MAI/MSPC).

Main Sources

Bill Kissane, ‘On the shock of civil war: cultural trauma and national identity in Finland and Ireland’, in Nations & Nationalism, vol. 26, no. 1 (2020), p. 35.

Eunan O’Halpin and Daithí Ó Corráin, The Dead of the Irish Revolution (Yale, 2020), p. 544.

‘Memorandum on the development of the forces, 1923-7’, p. 6, Military Archives of Ireland (hereafter IMA)/HS/A/0876.

Michael Hopkinson, Green against green: the Irish civil war (2nd ed., 2004), p. 127.

M.G. Valiulis, Portrait of a revolutionary: General Richard Mulcahy and the founding of the Irish Free State (Dublin, 1992), pp 173-4.

Irish Independent, 29 June 1922.

Irish Times, 8 July 1922.

MAI, Military Service Pensions Collection, 3D281, Elmer Loftus

Author’s bio:

Jack Kavanagh is a postdoctoral researcher based at UCD. His research is focused upon the development of the pro-Treaty forces during the Irish civil war and the spatial relationships between military recruitment and deployment.