Civilian Fatalities

Civilian Fatalities of the Irish Civil War

Andy Bielenberg

Archival advances at the Irish Military Archives and new research undertaken during the Decade of Centenaries (2012-2023) have given us a clearer picture of the combatant fatalities of the Irish Civil War. Our view of civilian fatalities, however, remains patchy. A series of valuable county studies has illuminated the conflict at local level, but the impact of the Civil War on civilians in large swathes of Ireland remains entirely uncharted. One of the more important aims of UCC’s Irish Civil War Fatalities Project was to build a more comprehensive picture of civilian fatalities across the entire country between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923.

Source Material

Various sources were consulted to achieve this objective, including specific newspapers, various compensation claims and military reports, but the most important advances were made through a full search of all death certificates in the Irish Free State area for the years 1922-23. While this source did not capture all civilian deaths, it certainly covered the great majority of them, and also provided information on the cause and place of death, occupation, and age. Once collected and entered into our database, this evidence provided a fuller picture of the geography and causes of civilian deaths and their social profile.

This project counted 371 civilians killed in the thirty-two counties between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923. This number is far lower than the 919 civilian dead between 1917-1921, (logged in 2020 by the ‘Dead of the Irish Revolution’ project), most of whom were killed during the Irish War of Independence period, 1919-21.

Chronology & Geography

Civilian fatalities were concentrated in the early stages of the Civil War and reached their peak for the entire conflict in July 1922, demonstrating the high cost of urban combat in Dublin, Limerick and Waterford in particular. Almost 60 per cent of the civilian fatalities occurred between June and November 1922, a five-month period covering the ‘conventional’ and first guerrilla phases of the Civil War, with a progressive decline thereafter.

| Table: Fatalities by affiliation in each three-month phase of the Civil War in the Twenty-Six Counties |

|---|

| Period | Civilians | NA | IRA | Total |

| Jun-Aug 1922 | 114 | 210 | 108 | 444 |

| Sept-Nov 1922 | 88 | 214 | 103 | 411 |

| Dec 1922-Feb 1923 | 78 | 111 | 107 | 300 |

| Mar-May 1923 | 56 | 102 | 108 | 271 |

| Total | 336 | 637 | 426 | 1426 |

In geographical terms, almost 47 per cent of civilian deaths in the twenty-six counties occurred in the province of Munster, with Leinster accounting for slightly less than 37 per cent and Connacht and the three southern Ulster counties combined accounting for a little over 16 per cent. The fatalities map reveals a significant concentration in Dublin city (the county with the highest absolute number) and also in Cork city, with lesser concentrations in urban Limerick and Waterford. The fundamentally different pattern evident north of the border in the timeframe covered by this project, reveals that the majority (59 per cent) of the far more limited number of victims were civilians. One of the few features that the fatalities in Northern Ireland shared with those in the south was the significant urban concentration (around Belfast).

From a county perspective, its worth noting that only two counties in the Free State area, Dublin and Cork, claimed more than fifty civilian deaths. The majority of counties (seventeen) counted fewer than eleven and in ten of those counties, the civilian death toll was between one and five. Wicklow was alone among the twenty-six counties to have had no civilian deaths and County Carlow posted only one. In most areas during the Civil War, as the fatality map reveals, civilian fatalities were relatively rare. The counties where the majority were killed included Dublin (79), Cork (57) and Limerick (29), which were major theatres of the conflict, and to a lesser extent Kerry (25), Tipperary (20), Waterford (16) and Mayo (13).

.jpg)

Fig 1. Map showing the locations of the 371 civilian fatalities in the thirty-two counties between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923

Age, gender & social class

Civilian deaths followed a significantly different pattern to combatant deaths. A little over 47 per cent of civilians fatalities in the twenty-six counties (where age was known) were aged between fifteen and thirty-four, which was a far lower share than for combatants. Unlike the combatants, civilian fatalities were spread across the entire age spectrum, with twenty-six under the age of fifteen and twenty-one aged sixty-five or older.

In gender terms, only 4.5 per cent of total fatalities in the Irish Civil War were women. Of these, only three were combatants (all Cumann na mBan members), while the remaining sixty-two were civilians. In age terms, female civilian fatalities displayed a somewhat different pattern to male civilian victims. While less than 28 per cent of male civilians killed (where age is known) were in the 1-24 age cohort, this group accounted for almost 56 per cent of female victims. Conversely, over 72 per cent of male civilians and 44 per cent of female civilians were over twenty-four years of age. Clearly, younger women and older male civilians were more likely to be in public spaces and thus caught in crossfire during the Civil War. Gender differences in fatality profiles were least notable among children who, during this period, played in the streets.

The social elite was relatively well represented among civilian fatalities. Over 10 per cent were listed as business owners or upper professionals like doctors, solicitors, and higher civil servants in comparison to just under 3 per cent of IRA fatalities and just over 2 percent of the National Army dead. More broadly speaking, civilian victims fell across a wider social spectrum of society than the belligerents.

Fig. 2 Crowds in Cork city welcome National Army troops after their arrival in 1922. Civilian casualities were concentrated in cities such as Cork and Dublin. [National Library of Ireland, HOGW 92]

Cause of Death

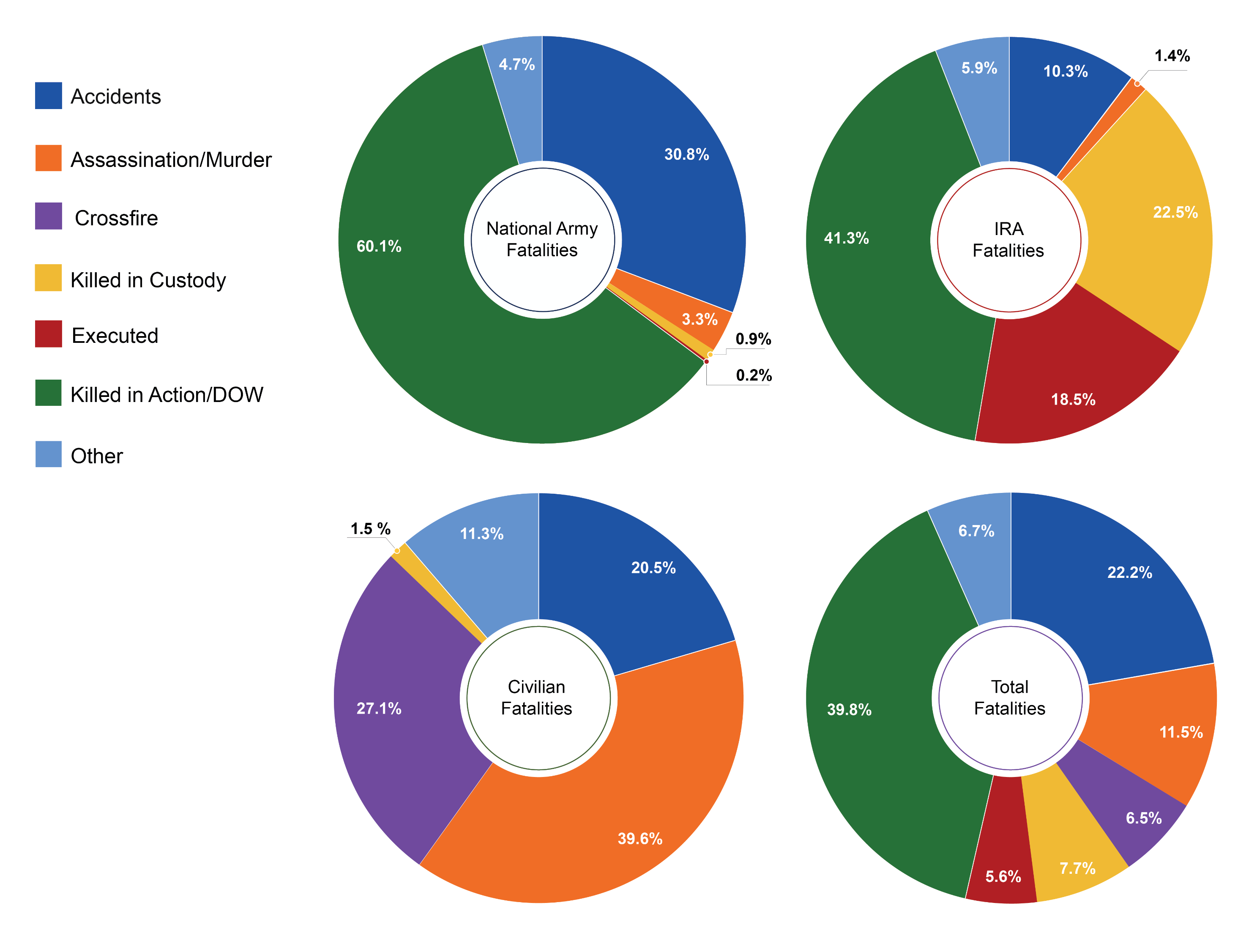

Over 27 per cent of civilians were killed in crossfire and over 20 per cent in accidents directly related to the military conflict. This latter category included fatalities as a result of accidentally discharged weapons or explosions; accidents involving military vehicles; heart attacks induced by military raids, and, in the case of Laurence Power, an insurance agent from County Waterford, drowning after falling from a bridge destroyed by republican forces on 2 March 1923. Despite the high level of civilian deaths by misadventure, or what might be termed ‘collateral damage’, almost 40 per cent could be clearly identified as deliberate, and the actual figure of deliberate killings was likely to have been higher still. Of this 40 per cent, about half occurred during spontaneous encounters between combatants and civilians. The National Army shot many more civilians than the IRA in such encounters, (fifty as compared to thirteen), usually at checkpoints when civilians ‘failed to halt’. A typical IRA shooting of a civilian, leaving aside the killing of informers, occurred during house raids.

This leaves another sixty-eight civilian deaths that were due to targeted assassination or murder. Uncertainty hangs over many civilian killings in the conflict. There were cases where the motives were apparently personal or agrarian rather than political. In some instances, bodies were found shot and labelled as informers, but the motives were later traced back to personal and apolitical grievances. Until quite late in the Civil War, IRA general orders laid out explicitly that civilians could not be killed as punishment for providing information to Free State forces.

While these orders were eventually rescinded and some civilians were shot as ‘spies’ by the anti-Treatyites, the thirteen or more killed was dramatically less than during the War of Independence, when, as Pádraig Óg Ó Ruairc notes, at least 191 civilians were executed by the IRA as suspected spies and informers. This was one of the major differences between the two conflicts, and partially accounts for the far lower civilian death toll during the Irish Civil War. Another likely reason for this significant disparity was that, due to significant local recruitment in the Civil War, the pro-Treaty forces had a far better knowledge of their adversaries than Crown forces during the War of Independence and did not have to depend on civilian informers in the locality to the same extent.

Fig 3. Pie charts showing cause of death in each category in the twenty-six counties between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923

Attacks on Property

Fatality figures are not the only measure of the impact of the Civil War on civilians who suffered severe disruption to their daily lives, to communications and commerce, and in some cases, dislocation, and destruction of property. In reprisal for the government’s execution policy, the anti-Treaty leadership ordered attacks on the homes and property of pro-Treaty supporters. A General Order issued in December 1922, for instance, declared that ‘all Free State supporters are traitors and deserve the latter’s stark fate, therefore their houses must be destroyed at once’.

Hundreds of houses owned by government supporters, senators, TDs and military officers were burnt, mostly in the winter of 1922-23, including nearly 200 mansions belonging to the old landed class, many of whom were former unionists. Such property destruction was rarely lethal, as the victims were generally given time to leave. Two exceptional cases were Emmet McGarry, the seven-year-old-son of pro-Treaty TD Seán McGarry, who died of burns after the family home in Fairview was set alight in December 1922, and Thomas Higgins, the sixty-four-year-old father of government minister, Kevin O’Higgins, who was shot dead by an IRA party that had come to burn the family home in Stradbally, County Laois in February 1923.

One of the defining features of the Irish Civil War was the relatively low level of civilian fatalities. Of the 1,426 fatalities in the twenty-six counties between 28 June 1922 and 24 May 1923, less than 24 per cent were civilians. The fact that the Civil War was an intra-nationalist conflict may have influenced this relatively low civilian share. In contrast, civilians made up some 39 per cent of victims during the Irish War of Independence (including some fatalities during the five-month Truce period after 11 July 1921). If we examine Northern Ireland alone between 1920-22, nearly 80 per cent of the fatalities were civilians. In a wider European comparative context, the Irish Civil War lacked a strong class dimension, while ethno-religious divisions were not a significant aspect of the conflict, all of which had a moderating impact on the civilian death toll.

Fatality Profiles

Civilian: Jeremiah Coleman

In many respects, thirty-four-year-old carter Jeremiah Coleman who was killed in September 1922 in an urban location in the vicinity of Cork city in the province of Munster was a typical civilian victim of the Civil War. He was not a victim of crossfire, but of a deliberate and targeted killing. Owing to the destruction wrought on the railway network by republicans in their attempt to disrupt trade and communications, Coleman was frequently hired to supply commodities to rural districts in Cork. On 2 September he left the city with a cart load of materials destined for Crookstown. Early the next morning, his body was discovered in his own cart, which his horse had returned to the place where it was stabled on Keyser’s Hill, an ancient lane in the shadow of Elizabeth Fort in Cork city. Coleman had been shot twice in the back and died instantly from a lacerated spinal column. While it is impossible a century later to know the circumstances, motives and precise location of his death, there is no doubt that the killing was deliberate.

Civilian: Angela Bridgeman

Twenty-three-year-old Angela Bridgeman, originally from County Limerick, was working as a waitress in Dublin city in 1922. She had the misfortune to be travelling on a tram through Harcourt Street on 4 December 1922 when a National Army patrol there was ambushed by republicans. She was caught in crossfire during the affray and taken to the Meath Hospital where she succumbed to her head wounds later that day. Her death, reported in the Irish Times on 5 December, illustrates the higher risk to younger females who had to travel to work and is representative of civilians who lost their lives as they inadvertently passed through urban conflict zones. Angela Bridgeman is also representative of the many civilians in Dublin (the largest centre of civilian fatalities in absolute terms), who lost their lives in random circumstances throughout the conflict, and long after the initial battle for Dublin was over.