- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Easter Week Timeline: Friday 28 April 1916

The arrival in Dublin of General Sir John Maxwell on the Friday of the Rising sparked what would become a turning point not just in the rebellion, but in the Irish revolution that would continue for the next six years.

His decisions regarding executions, and to arrest Irish Volunteers and other activists in the following weeks, would be the actions on which public opinion would quickly turn in favour of those behind the unsuccessful rebellion.

It was the beginning of the end for the main garrison of the rebels in the GPO, with fires and shell damage forcing them to consider an evacuation.

In the early hours, other landmark buildings on Sackville Street such as the Imperial Hotel and Clery’s department store were destroyed by fire.

9.30am

As President of the Irish Republic and commander of the Army of the Irish Republic, Patrick Pearse issued a statement acknowledging the difficult situation, but paying “homage to the gallantry of the soldiers of Irish freedom who have during the past four days been writing with fire and steel the most glorious chapter in the later history of Ireland.”

“Let me, who have led them into this, speak, in my own, and in my fellow-commanders’ names, and in the name of Ireland, present and to come, their praise, and ask them who come after them to remember them.

“For four days they have fought and toiled, almost without cessation, almost without sleep, and in the intervals of fighting they have sung songs of the freedom of Ireland,” he wrote.

10.30am

The Fingal Battalion of the Irish Volunteers in north Dublin began an attack on the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks at Ashbourne, Co Meath. After several hours of battle, including the arrival of police reinforcements after the barracks surrendered, eight RIC members and two Volunteers were dead. The encounter brought battalion commandant Thomas Ashe to prominence but he would die on hunger strike in jail in 1917. Richard Mulcahy, the other Volunteer leader at the Battle of Ashbourne, would later become chief-of-staff of the IRA and succeeded Michael Collins as Free State Army commander-in-chief.

8.00pm

The GPO needing to be evacuated, an advance party tried to lead the way towards Moore Street. In the process, prominent Irish Volunteers officer Michael Joseph O’Rahilly was wounded and died alone in Moore Lane. The main garrison later escaped the GPO through back streets, the leaders occupying houses in Moore Street.

The next day would see the decision taken by Pearse and the other members of the Provisional Government to bring an end to the ongoing deaths of civilians, and to issue the formal surrender that ended the Rising.

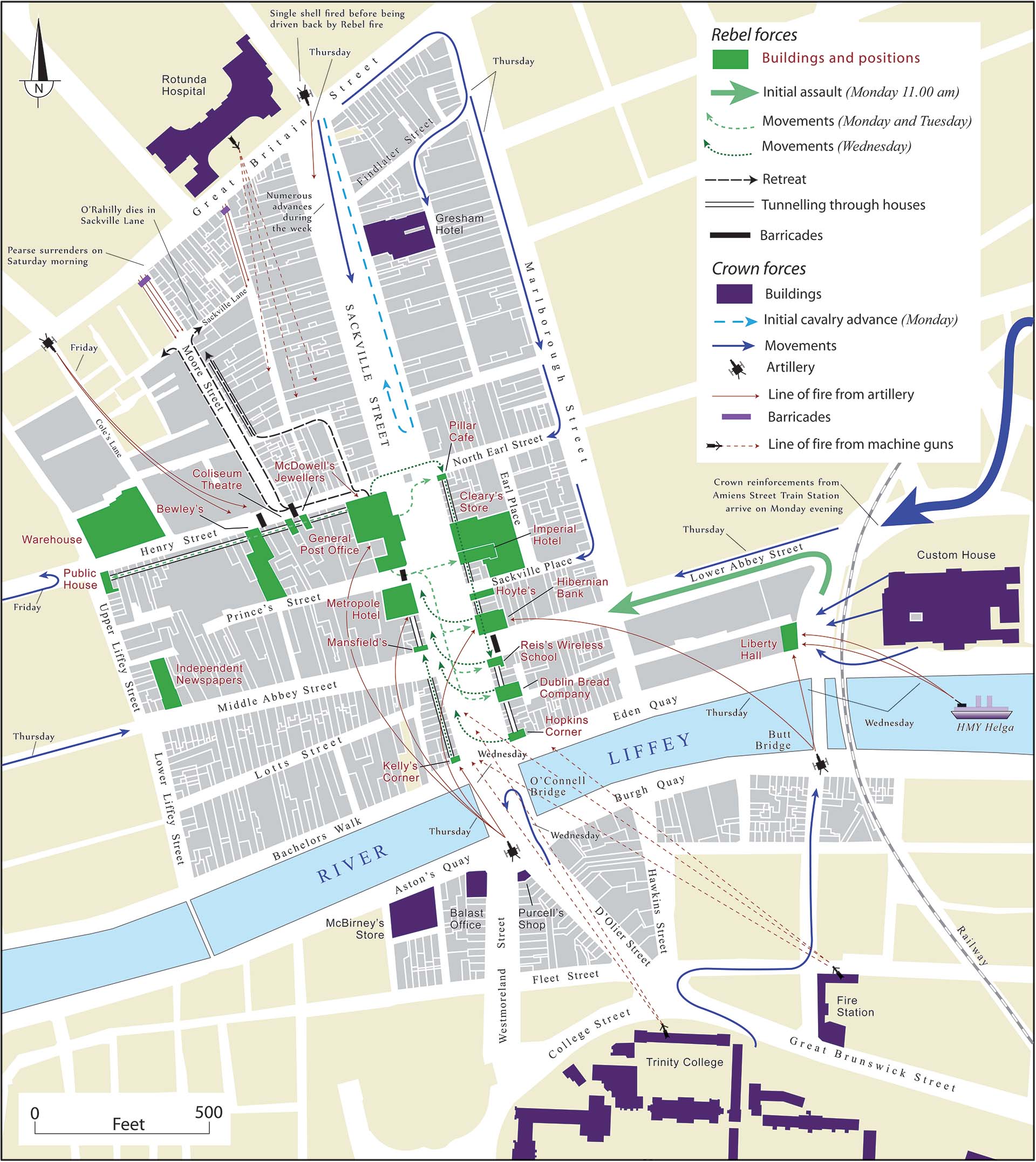

GPO, Sackville Street: Map & Caption

While the GPO symbolized the Easter Rising, the building was only one of many held by the rebels in the larger Sackville Street (O’Connell Street) area. Numerous rebel outposts commanded the approaches into Lower Sackville Street, which were connected by a series of tunnels dug through neighbouring buildings. For the first three days of fighting the GPO escaped direct attack, and was only subjected to British sniper fire and an ill-conceived British cavalry charge on Monday, 24 April.

Some of the fiercest fighting occurred on the east side of Lower Sackville Street, as small garrisons tried to hold back British troops surging from Marlborough Street and Lower Abbey Street. Kelly’s Corner and Hopkin’s Corner were also subjected to fierce fusillades from British forces operating out of Trinity College across the River Liffey.

A turning point occurred on Thursday, 27 April when British field artillery pieces (18 pounders) positioned on Sackville Street and Butt Bridge shelled rebel positions, setting many buildings ablaze. By nightfall, the rebels had been burned out of the east side of Sackville Street, with those fighters either captured or forced to retreat to the GPO. On early Friday, artillery shells fell on the GPO and set it alight. As the building began to disintegrate on Friday evening, the garrison retreated under fire across Henry Street, and burrowed into small shops and tenements on Moore Street and Moore Lane. Michael O’Rahilly (‘The O’Rahilly’) led a breakout attempt towards Great Britain (Parnell) Street, but his force was cut down on Moore Street by heavy British fire.

The rebels found themselves trapped in a small area, surrounded by British troops and facing renewed shelling. Fearing the destruction of his force and the infliction of heavy casualties on the adjacent civilian population, Patrick Pearse ordered a surrender late on Saturday morning, 29 April. The rebellion was over.

[The following sources were used in the mapping of the 1916 garrisons for the Atlas of the Irish Revolution (CUP, 2017): D. Molyneux and D. Kelly, When The Clock Struck in 1916 Close-Quarter Combat in the Easter Rising (Cork, 2015), C. Townshend, Easter 1916 The Irish Rebellion (London, 2005); M. Caulfield, The Easter Rebellion (Dublin, 1995); F. McGarry, The Rising Ireland: Easter 1916 (Oxford, 2011); P. O'Brien, (2010). Uncommon Valour 1916 & the Battle for the south Dublin Union (Cork: 2010) W. Brennan-Whitmore, The Easter Rising from Behind the Barricades (Dublin, 2013). Bureau of Military History Witness Statements - WS 162 (John Shouldice); WS 201 (Nicholas Laffan); WS 255 (Thomas Smart); WS 314 (Liam O’Carroll); WS 393 (Seamus O’Sullivan); WS 521 (Jerry Golden); WS 842 (Sean Kennedy); WS 1686 (Capt R. Henderson); WS 428 (Thomas Devine); WS 157 (Joseph O’Connor); WS 310 (James Grace); WS 377 (Peadar O’Mara); WS 433 (Simon Donnelly); WS 158 (Seamus Kenny): OSI Map Viewer http://maps.osi.ie/publicviewer/#V2,591271,743300,1,9]