1. For example, an IRA witness recorded that John Good of Cork city had been shot dead. See Michael Murphy’s Witness Statement 1547, 38 (Bureau of Military History [hereafter BMH], Dublin). But the Cork Weekly News of 19 March 1921 reported that Good had been transferred to the Cork Central Military Hospital and that his condition was not regarded as serious. We have not included him. He has been counted as a death, however, by Gerard Murphy in his book The Year of Disappearances: Political Killings in Cork, 1921-1922 (Dublin, 2010), 41, 282. Murphy also includes others for whom we have not found plausible evidence. >

2. This assessment is based on the registration of homicides returned by county in the Annual Reports of the Registrar General, tabulated by county, in Andy Bielenberg, ‘Fatalities in the Irish Revolution’, in Atlas of the Irish Revolution, ed. John Crowley, Donal Ó Drisceoil, and Mike Murphy (New York and Cork, 2017), in addition to a breakdown of fatalities given by county in Eunan O’Halpin and Daithí Ó Corráin, The Dead of the Irish Revolution (New Haven and London, 2020), 543 (which includes deaths in 1917-18 and after the Truce in 1921). >

3. While most of the fatalities named in Hart’s text appear in our database, there were a few for which we could find no record indicating that the persons in question had died, while at least one was classified incorrectly. For example, Joseph Bolster of Banteer, reputedly killed for his refusal to contribute to the railway strikers’ fund, could not be found in the police reports cited by Hart or in any other source that we examined; and William Vanston, reputedly of Douglas, was actually shot in Queen’s County. In addition, we have found no record to demonstrate that a ‘Din Din’ Riordan was killed. Hart reports two Volunteer deaths in a bomb explosion in Cork city in 1919, when in fact there was only one. See Peter Hart, The IRA and Its Enemies: Violence and Community in Cork, 1916-1923 (Oxford, 1998). The removal of these doubtful cases would reduce Hart’s total, but other researchers may be able to locate sources to confirm the deaths of some; we have not included them.

4. Times (London), 9, 10, 11 Sept. 1919.

5. Seán A. Murphy, Kilmichael: A Battlefield Study (Skibbereen, 2014).

6. William J. Lowe, ‘The War against the R.I.C., 1919-21’, Éire-Ireland 37:3-4 (Fall/Winter 2002).

7. Sinn Féin and Republican Suspects (Timothy Quinlisk), CO 904/213/365 (National Archives, Kew); Irish Independent, 23 Feb. 1920.

8. William Sheehan, A Hard Local War: The British Army and the Guerrilla War in Cork, 1919-1921 (Stroud, Gloucestershire, 2011), 158.

9. Ibid.

10. See, for example, The Last Post (2nd ed., Dublin, 1985); Commonwealth War Graves Commission; Richard Abbott, Police Casualties in Ireland, 1919-1922 (Cork and Dublin, 2000). For the IRA in County Cork the Roll of Honour of the Cork No. 1 Brigade, published in 1963 in a pamphlet on the Republican Plot in St Finbarr’s Cemetery in Cork city, provides the most comprehensive and exacting return for any brigade area in the county and covers the one with by far the highest fatalities. Copies of this pamphlet are deposited in the Cork Public Museum, Fitzgerald Park, Cork city, and in Special Collections, Q-1, the Boole Library, University College Cork (MP 941.5081 BRIO).

11. With regard to the attack at Furious Pier on Bere Island, one witness declared: ‘This operation was carried out in response to an order from H.Q., 1st Southern Division, and as a reprisal for the execution of I.R.A. prisoners in Cork.’ See Eugene Dunne’s WS 1537, 8 (BMH). See also Daniel Cashman’s WS 1523, 12 (BMH); Florence O’Donoghue, No Other Law: The Story of Liam Lynch and the Irish Republican Army, 1916-1923 (Dublin, 1954), 154-58. Attacks in Kerry and Limerick on the same date resulted in the deaths of two additional policemen. See Abbott, Police Casualties, 239-41.

12. Dorothy Macardle provides a full list of those executed in The Irish Republic (Corgi Books ed., London, 1968), 912-13. County Cork accounted for 13 of the 24 executions; these 13 were all carried out in Cork city in 1921.

13. Murphy, Year of Disappearances, passim. Recently revealed pension evidence suggests that killings in the Knockraha area and the Rea (which may include a number of undocumented cases) conform to this pattern. Killings largely took place during the War of Independence—roughly in the year leading up to the Truce in July 1921, with few killed there before or after this window. See Pension Evidence of Edward Moloney, MSP34/REF27648 (Military Archives, Dublin). The problem with much of the evidence relating to killings at Knockraha is that the critical evidence on numbers is directly connected with Martin Corry, a problematic witness. Question marks, for example, must be raised around his claims to have killed and disappeared 18 Cameron Highlanders. For the War of Independence period there is limited documentary evidence to verify these claims. Disappearances of soldiers from other regiments stationed in County Cork, such as the Manchesters, or indeed disappearances from the RIC, in most cases appear to have left some documentary trail. The possibility that Corry was exaggerating, needs to be interrogated more critically.

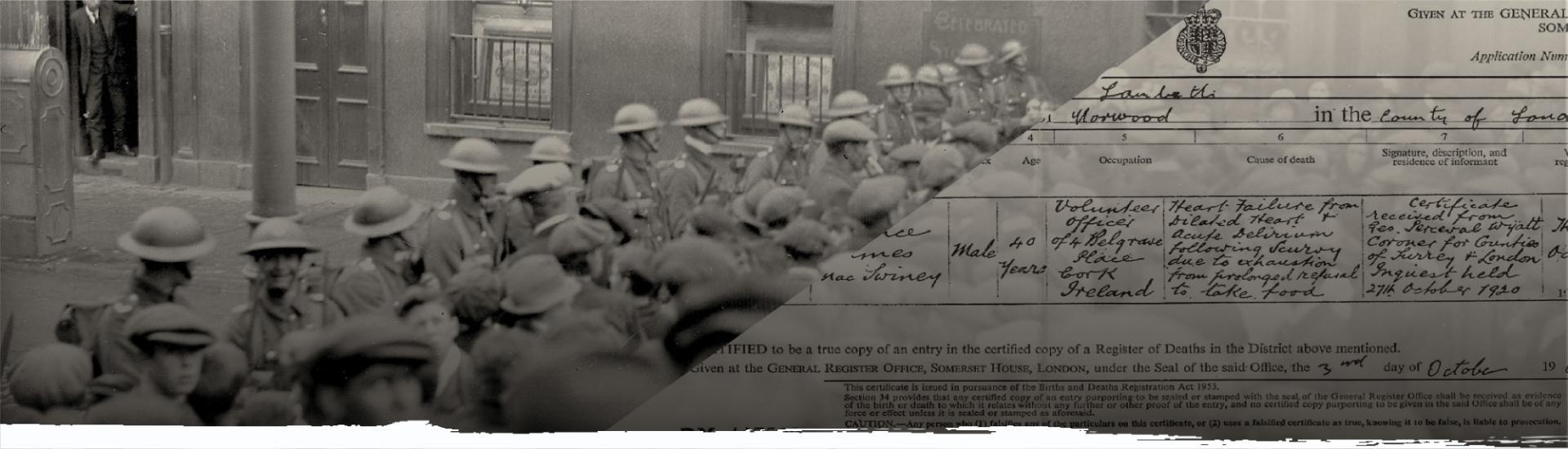

14. We therefore do not include, for example, Terence MacSwiney, the Lord Mayor of Cork who died on hunger strike in Britain (see Francis Costello, Enduring the Most: The Life and Death of Terence MacSwiney [Dingle, 1995]), or the civilian George Tilson, who cut his own throat on a train destined for London (see John Borgonovo, Spies, Informers, and the ‘Anti-Sinn Féin’ Society: The Intelligence War in Cork City, 1920-1921 [Dublin, 2007]), or Second Lieutenant A.F.M. Towers, fatally wounded at Crossbarry, who later died in Britain in 1923 (see W. H. Kautt, Ambushes and Armour, 1919-1921: The Irish Rebellion [Dublin, 2010], 151, fn. 70).

15. We have excluded the following persons who died (among others for similar reasons): Michael Blanchfield (CWN, 27 Dec. 1919), whose death appears to resulted from a robbery; and Denis Lehane (Michael Leahy Interview, Ernie O’Malley Notebooks, P17b/108 [University College Dublin Archives, hereafter UCDA]), for whom we could discover only one source naming him.

16. For estimates of the casualties suffered on both sides in this campaign, see John Borgonovo, The Battle for Cork: July-August 1922 (Cork, 2011), 109. A comprehensive listing of national army soldiers killed across Ireland throughout the civil war period has been recently published; James Langton, The forgotten fallen; National Army soldiers who died during the Irish Civil War (Lucan, 2019).

17. John Dorney, ‘Casualties of the Irish Civil War in County Cork’, in The Irish Story, https://www.theirishstory.com/2019/07/14/casualties-of-the-irish-civil-war-in-county-cork/#.YW9Qqi1h1m8 (accessed 10 Oct. 2021). This article will hereafter be cited as ‘Cork CW Casualties’.

18. ‘Cork CW Casualties’.

19. Dorney notes that fatalities among National Army troops in accidents ‘were nearly five times as common’ as those among IRA soldiers in Cork. See ‘Cork CW Casualties’.

20. For the chief weaknesses and shortcomings of the Cork IRA in this conflict, see Michael Hopkinson’s classic work Green against Green: The Irish Civil War (Dublin, 1988), esp. 162-65.

21. Dorothy Macardle, Tragedies of Kerry, 1922-1923 (16th ed., Dublin: Irish Freedom Press, 1998; originally published 1924); ‘The Civil War in Kerry’, in Atlas of the Irish Revolution, 716-17.

22. Sean Boyne, Emmet Dalton: Somme Soldier, Irish General, Film Pioneer (Sallins, Co. Kildare, 2015), 185.

23. ‘Cork CW Casualties’.

24. Hart, The IRA and Its Enemies, 121, fn. 56.

25. Dorney, ‘Cork CW Casualties’; Keane, Cork’s Revolutionary Dead, 289-376; Hart, The IRA and Its Enemies, 121. Keane’s list includes some individuals who died outside County Cork.