In This Section

- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

The immediate political response to the Rising was a mixture of outright hostility from a range of sources – the government, certain sections of the Catholic hierarchy, unionists across the whole of Ireland, and the home rule constituency – and an ominous silence from others.

By Gabriel Doherty, UCC

Faced with the tasks of identifying and burying the dead (it should be noted that the remains of two children were never claimed by their families, and they were buried incognito), tending the wounded, demolishing unstable buildings and clearing the streets of rubble, restoring food and gas supplies and communication methods such as railways, posts and telegraphs meant that the civic authorities in Dublin had their hands full for quite some time.

The military authorities, too, had plenty to occupy them, given that the declaration of martial law had, in effect, transferred the powers of the government of Ireland into their hands.

More to the point, there was the matter of putting those involved in the Rising (more accurately, those deemed to have held leadership positions) for their actions, and carrying out the sentences of the courts martial – up to, and including, the execution of fifteen individuals (fourteen in Dublin, plus Thomas Kent in Cork; Roger Casement was, of course, subject to a conventional civil trial, albeit on a charge of treason, later in the Summer).

Video: In this clip Fergal Keane reveals the story of the Easter Rising and how it changed public opinion as rebel leaders became martyrs when they were executed by British forces.

The Government in London faced more vexed problems still, not the least of which was to how to prevent this new bout of Irish disorder from having a disturbing impact on the main task in hand, which was to wage, and win, the Great War.

Faced with demands from unionists for swift justice/vengeance, and from constitutionalists for the immediate implementation of the home rule Act, and all the time needing to maintain the flow of recruits from both sides of the divide, there was no obvious ‘right’ path to take – yet to fail to take action would itself produce adverse consequences.

In the event the pace was forced by an unlikely agent – Bishop Edward Thomas O’Dwyer, of the diocese of Limerick – one of the longest‐serving Catholic bishops in Ireland, who had started out with the reputation for being pro‐British, but who had become increasingly waspish on the ‘national question’ in recent years.

In late May 1916, he wrote a scathing reply to a request from General Maxwell that he rein in fervently nationalist priests in his diocese. Describing Maxwell as a military dictator, his letter opened up the Pandora’s box of public criticism of the government, and was proof that there existed within the upper echelons of the church sympathy for even the most physical force separatist position.

This was undoubtedly a key turning point …

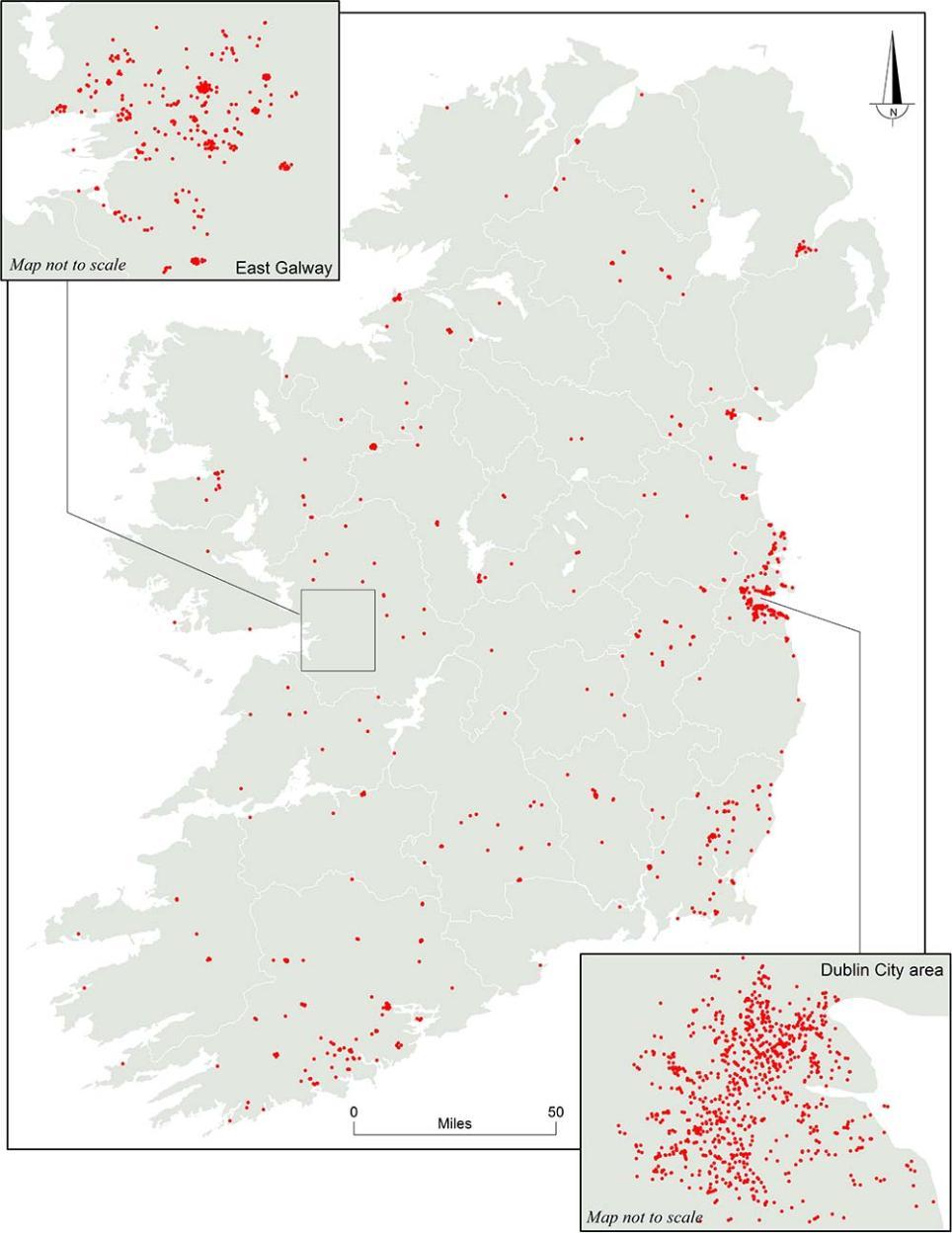

Prisoners Deported to Britain in 1916 : Map & Caption

From the Atlas of the Irish Revolution, (CUP, 2017)

In the weeks following the 1916 Rising thousands of people were arrested, imprisoned and interned with almost 2,500 deported to various detention centres in Britain. The military authorities released lists showing the names and addresses of those deported, the date deported, and the place detained. These lists were included in the Sinn Féin Rebellion Handbook, Easter 1916 published by the Weekly Irish Times.

In all, twenty lists were issued by the military authorities, covering the period 1 May to 16 June 1916. This map was created by plotting the addresses of the 2,486 persons listed as detained and deported during May and June 1916. On some dates multiple groups were deported, for example, on 20 May four different groups were sent to Perth, Glasgow, Woking and Lewis. The map highlights in particular the impact of the Rising outside of Dublin, for example in counties such as Galway and Wexford. As William Murphy explains: 'When commentators mention the Easter Rising as a turning point, invariably they focus on the executions, but the widespread arrests (and subsequent internments and imprisonments) weighed significantly upon the attitudes of hundreds of families and communities and upon wider public opinion throughout the country. For over a year these prisoners remained a live issue upon which separatists focused attention. They became breathing representations of the government's alleged high-handedness. They were grievance embodied’ [See W. Murphy, Political Imprisonment and the Irish, 1912-1921 (Oxford, 2014), p. 57]