Tracing the Past

Professor Pádraig Ó Macháin is the lead of Inks and Skins, an Irish Research Council Advanced Laureate project seeking to unlock the secrets of ancient Irish manuscripts. Here, Pádraig and researchers Anna Hoffmann and Veronica Biolcati share how combining the humanities with science can offer new insights into our heritage. In conversation with Jane Haynes.

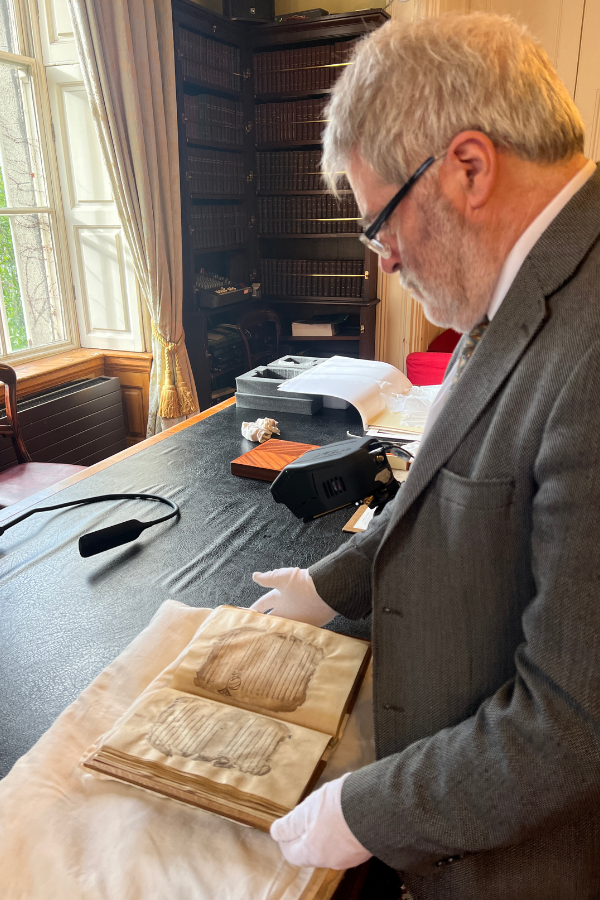

It is unsurprising that, after 40 years of research in the field, the one quality that Pádraig Ó Macháin endeavours to instil in his students, before they come into contact with any of Ireland’s ancient Gaelic manuscripts, is humility. Completely unique, centuries-old and a labour of painstaking dedication by their scribes, each manuscript is a living artefact that offers an unprecedented insight into Ireland’s heritage.

“These are witnesses – of a very eloquent variety – to the past. They are still living today, but they bear witness to the past times in which they were created. You can’t say that about many other artefacts,” says Pádraig, Professor and Head of Modern Irish at UCC.

Pádraig is the lead of Inks and Skins, an interdisciplinary project between UCC’s Department of Modern Irish and Tyndall National Institute. Funded by the Irish Research Council (IRC), the project is dedicated to the investigation of the materiality of late medieval Gaelic manuscripts. Working alongside senior researcher Dr Daniela Iacopino (Tyndall), IRC Advanced Laureate Scholars Anna Hoffmann (Modern Irish) and Veronica Biolcati (Tyndall), and a team of research fellows and associates, Pádraig is working to uncover the secrets held within these ancient artefacts.

The anchor manuscript in Inks and Skins is the Book of Uí Mhaine: a large vellum manuscript of Irish tradition, assembled for the O’Kelly family – tribal leaders in East Galway – in around 1390. The manuscript, a key indicator of what life was like in early medieval Irish society, contains everything from poetry to local genealogies. The genius of this project lies in the research intersection between the humanities and the sciences: what literary observations are being made about the Book of Uí Mhaine are being analysed and proven through the most advanced technology available.

“These are witnesses – of a very eloquent variety – to the past. They are still living today, but they bear witness to the past times in which they were created. You can’t say that about many other artefacts” - Professor Pádraig Ó Macháin

It all starts with Pádraig who, with a decades-long career in ancient manuscript research, is arguably one of the greatest authorities in the field. He began his research shortly after completing his PhD in Scotland, first cataloguing a manuscript belonging to Sir Walter Scott. After stints at the National Library of Scotland and the university library in Edinburgh, Pádraig went on to spend a decade cataloguing manuscripts for the Institute of Advanced Studies in Dublin, in the National Library of Ireland. In 1998, Pádraig led the first digitisation project of manuscripts in Ireland, Irish Script on Screen. For the first time, ancient Irish manuscripts were available for the public to view online, free of charge – this, Pádraig says, brought a whole new level of appreciation for these markers of ancient Irish heritage. He describes receiving the IRC Advanced Laureate Award in 2019 as “a game-changer”, enabling him to return to the manuscripts he had digitised long ago and examine what was beneath the text.

Central to the team are the IRC Advanced Laureate Scholars; with New York native Anna Hoffmann working on the visual analysis of the manuscripts while Veronica Biolcati, from Northern Italy, focuses on the materiality of the manuscripts through scientific analysis. Both are deeply appreciative of the opportunity to analyse these ancient artefacts and draw out the secrets they tell about fourteenth-century Irish heritage.

For Anna – a graduate of European History from Barnard College, Columbia University – it was during a semester at UCC when she first became captivated by Ireland’s ancient manuscripts.

“I took Pádraig’s class, which was about medieval manuscripts, and I just totally loved it. As an American, we don’t have that length of history that you have here in Ireland, and it’s so fascinating to think that you have these artefacts that are hundreds of years old,” she explains.

Discussing her work on the project, she says: “It’s not about the content, it’s about the materials: the parchment they’re made out of – which was almost always calfskin in Irish manuscripts, and the inks; pretty much the whole process, from beginning to end, of how these individuals made these manuscripts.”

Anna’s work involves looking at the manuscript, page by page, and writing down every feature – from holes to scraping marks, rulings and layouts – and determining what elements such as ageing, staining and insect infestations tell about the environment in which the manuscript was created.

Veronica – whose degrees from the Universities of Ferrara and Bologna intersect both science and cultural heritage – conducts the scientific analysis, which involves X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) and other analytical techniques. The XRF spectrometer ‘zaps’ the manuscript with x-ray at a particular micro-point, exciting the atoms in such a way that they reveal their identity. The machine then uses this information to create a graph of all the minerals within the ink, pigments and parchment, which is then used to build a book profile and inform research of the overall artefact.

“There are many questions to answer about the manuscripts,” explains Veronica. “We are looking at the makeup of the animal skin – the treatment during the parchment production, the animal species. You can even find out where those animals are from, which could help to construct the trade markets between Ireland and other countries at that time.”

The application of scientific technology on these literary texts has already turned up some interesting results, says Pádraig, referencing a particular finger-print methodology: “Recently, we were able to construct a histogram of the various colours being used by the different scribes, and what that allowed us to do was to show what scribes were working together very closely. The histogram is almost like a window into the scribing work itself and shows the association, the friendships and the working patterns of the scribes who were collaborating.”

"As an American, we don’t have that length of history that you have here in Ireland, and it’s so fascinating to think that you have these artefacts that are hundreds of years old" - Anna Hoffmann

Pádraig describes it as “an honour” to have the opportunity to work on these texts, and the same sentiment is shared by both Anna and Veronica.

“It’s a great privilege to be working with these materials that most people don’t know exist. They carry information in terms of the stories and folklore, the genealogies; but also, the materials tell us so much about the culture, and how they lived and what they valued at the time – which is very different from our society now. So, I think it’s important to keep these visible, in a collective cultural consciousness,” says Anna.

“It should be something that you [the Irish] really value, because it is so rare in the world and so well-valued by other people,” adds Veronica.

For Pádraig, while it’s exciting to have the opportunity to continue and build upon his decades-long research, his goal for Inks and Skins is to share the stories and previously hidden fragments of our heritage with future generations.

“The crucial thing about it is that we have very few items from the Middle Ages or later periods in Ireland that speak to us so eloquently as these manuscripts,” he explains.

“The people who made these books may have been impoverished, they may have been famished; but I think they were way ahead of us in our understanding of the Irish tradition. And if you understand that, and if you approach these books with humility and patience, you’ll be rewarded in your studies; it’ll give back a lot more to you, and you’ll feel enriched.

“That’s really what I want to pass on to my students: a sense of the value of historic artefacts, which is not a monetary value – it’s a cultural value and an intellectual value and a human value. If I can do that, I think I’ll have done my job.”

Visit the Inks and Skins website for more information.

Photography: Diane Cusack