Features

Samantha Barry

- 21 Nov 2016

(7 minute read)

Being at the heart of the American presidential election was just one aspect of UCC graduate Samantha Barry’s job as head of social media at CNN. The Cork woman tells Clodagh Finn about her meteoric rise to fame in the digital world

She interviewed Donald Trump in a toilet in Miami, spoke to Hillary Clinton backstage and talked to Bernie Sanders and every other candidate in the recently-held US presidential election.

Samantha Barry, UCC graduate and head of social media at CNN, was at the very heart of the 2016 election, though she’s quick to clarify that her Snapchat interview with Trump took place in a toilet because that was the only place they could set up on the day.

The fact that Trump was even willing to do a Snapchat interview reveals just how vital a role social media played in the election.

“It had a huge part to play,” says 34-year-old Samantha. “You saw that in the readiness of the candidates to give the extra stories and sidebars necessary for an Instagram and a Facebook audience.”

Presidential debates trended online

From the outset of the primaries, CNN turned two-hour presidential debates into trending phenomena on Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter and Facebook.

It’s a brave new world and Samantha Barry, a native of Ballincollig, Cork, is at the forefront of it. Since she graduated with an Arts degree (English and Psychology) from University College Cork in 2002, she has gone on to earn a name as a world-renowned social media expert who is invited to share her expertise at conferences and universities all over the world.

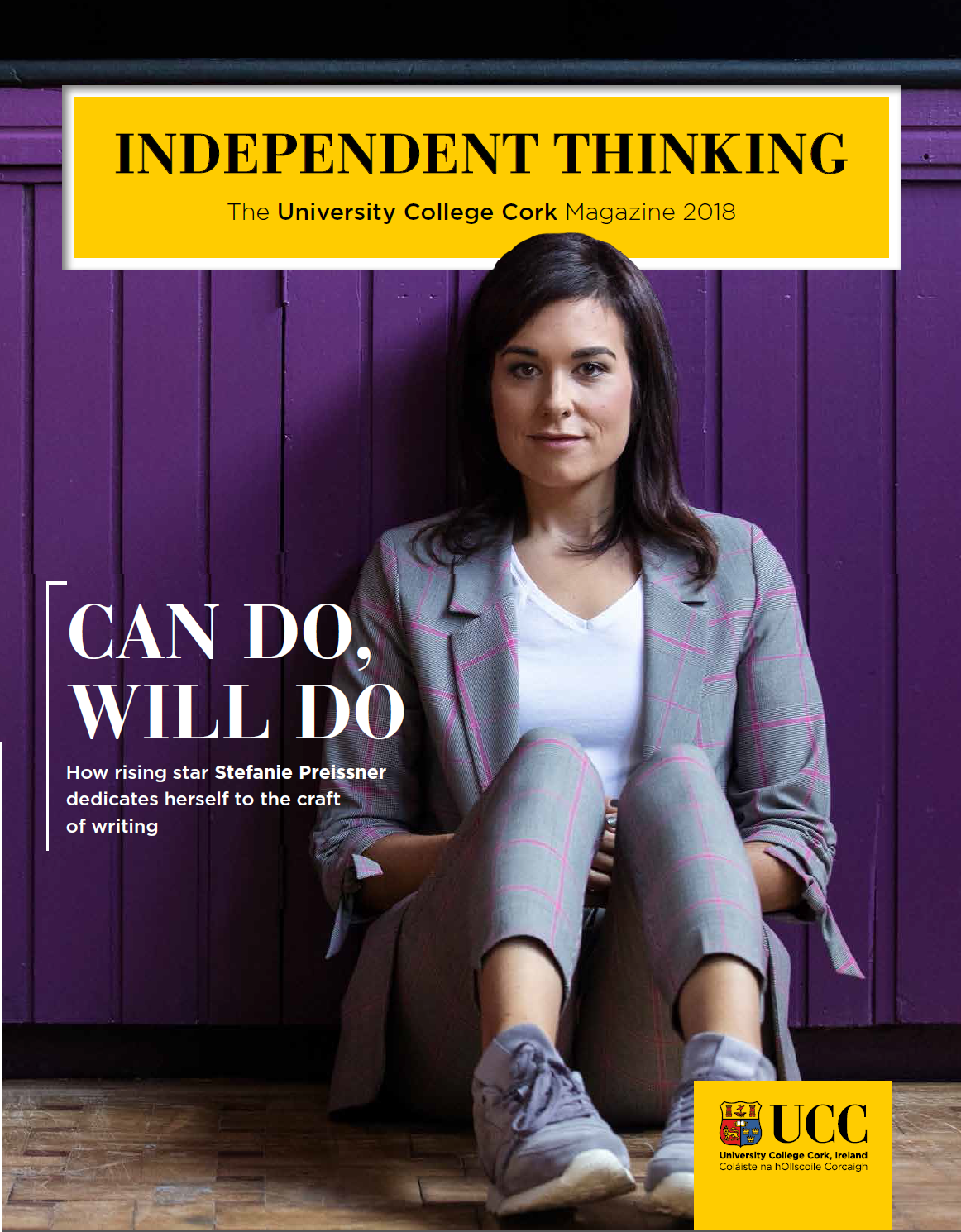

Samantha takes Manhattan: Cork woman Samantha Barry has helped to transform CNN from a TV news network to a 24-hour global multiplatform network. Pictures: Michael Appleton

From London to New York

Two years ago, she was headhunted from BBC World News in London to run CNN’s growing social media division.

From her New York office, she now oversees a staff of 30-plus people and has helped to transform CNN from a TV news network into a 24-hour global multiplatform network.

She strives – and this is her mantra, she tells us – “to create a CNN news habit for every generation on every platform”. “That means reaching people who don’t have a cable subscription. That means reaching people in Africa who have leapfrogged desktops and are going straight to mobile and social. No matter where people live, they know they can come to us and we are going to serve them up great stories and information in a way that they want to consume it.”

Ask her about her job and she’ll tell you she “absolutely loves it”, but that’s abundantly clear from the way she talks about her life, her work and, yes, believe it or not, her downtime – she makes sure to spend time doing the things she loves, such as going to the theatre, the cinema and having dinner with friends.

Most mornings start at 5.30am or 6am and the first thing she does is look at her emails on her mobile – it’s been on all night. She then checks her WhatsApp groups, Facebook, Twitter and CNN’s messaging apps.

“Then, I grab a coffee on the run. I’ve massively embraced the New York way of life, which is to order everything. It’s a rare privilege to cook dinner,” she says.

The office day goes by in a heartbeat – from 7.30am to 6pm – then, she tries to shut off for a few hours before tuning in again to keep an eye on primetime coverage and what is coming out of Hong Kong as it wakes.

Digital journey began in UCC

"I wrote for the University Examiner. I did three radio shows on the university radio. I just put my hand up and tried stuff"

It’s a long way from her student days at UCC, though she says her digital journey began the week she started college. “I tell the story that the first email address I ever had was in UCC. The first mobile phone I got was from Bank of Ireland. They were offering new students who signed up in 1999 a free Nokia flip phone,” Samantha says, adding that her US colleagues can’t believe that happened as late as 1999.

But what really stands out from her student days is the way UCC gave her an opportunity to put her hand up: “I don’t mean in class. I mean for things that could potentially put you down the path of where you were going to go. I wrote for the University Examiner. I did three radio shows on the university radio. I just put my hand up and tried stuff,” she says, advising others to do the same.

She says she loved the classes too: “I remember one of my favourite classes in English looked at how Shakespeare had influenced movies of the time. I adored going in there. I remember doing old English too, which I found very hard, but it stays with you.”

Did her time there help her get to where she is now?

“Absolutely. It helped me hone my skills and gave me confidence in journalism and made me feel that I could do this. It really started me on the path to working at the BBC.”

Picture: Rowan Davenport and Chris Wright

RTÉ to the BBC

After graduating from UCC, she went on to do an MA in Journalism at Dublin City University and from that got a job at RTÉ.

“When you grow up listening to a radio station and the next thing you are on the radio reading the news – ok, it might be at 3 o’clock in the morning but it’s still the news – it’s kind of fun.”

At 24, she took a year off to go to Australia and took up a job as lunchtime reporter at Newstalk radio when she came home. She still recalls a week-long series she did on Ireland’s most dilapidated secondary schools, as one of the highlights of her career.

She stayed at Newstalk for a year and a half, but the travel bug had bitten. In 2009, she went to South America and while there she got what she describes as a “very offbeat opportunity” to go to Papua New Guinea with ABC to train young reporters.

“That was the first lightbulb moment. Feature phones had just arrived in Papua New Guinea and had changed how everyone communicated. I set up Facebook pages for 13 radio stations and then, I said – wait a second – this thing that we call social media is changing not only how we communicate but how we consume news.”

After a year and a half there, she had a stint in Pakistan – “it was amazing and fascinating” – before going to London to work at BBC World News and BBC Media Action.

“They sent me to a lot of amazing places, including Burma,” she says, mentioning another career highlight.

“When I went there first in 2012, I sat in a room with about 100 young journalists and I asked if anybody had a mobile phone. One Burmese guy put up his hand and put what can only be described as a satellite phone on the desk. Nobody else in the room had a mobile phone.”

Two short years later, Samantha Barry walked off the tarmac in Yangon airport and was astounded to see how radically things had changed. “Everybody had a mobile phone, from the taxi driver to the monk I met. And a lot of them were getting their news from Facebook or messaging apps. It was an amplified version of what has been happening all around the world.”

Seismic shift in behaviour

She weighs the pros and cons carefully when asked if she thinks the seismic shift in behaviour, prompted by innovations in digital technology, is a good or a bad thing.

On the downside, she says cyberbullying is a real problem, though publishers and platforms are trying to combat it. “Sometimes the comments section of CNN is not a nice place to be.”

On balance, however, she thinks information is a real equaliser. “With this little thing,” she says tapping her iPhone, “so many people have access to information that they never had before.”

Another upside is that technology has allowed her to stay in touch with friends and family. “I am so connected to my family in Ireland because of WhatsApp. I Facetime my sister Davina, in Sweden and my brother Brendan, in Barcelona.

She Skypes her parents Máiréad and David in Bantry, Co Cork, and WhatsApps her mum. “We are every Irish parent’s worst nightmare; none of us lives at home. My dad had to suck it up and buy wifi for the house.”

Looking ahead, she says the future of news-gathering and news consumption is very exciting. While people on social media tend to live in a kind of self-congratulatory bubble that reflects their existing views, sometimes, big, important news stories penetrate that filter.

The most recent example was the picture of the bloodied Syrian boy Omran Daqneesh, photographed in an ambulance.

“The reach of that on social was huge. People shared that story who had never shared a story on Syria before. When people do that, we say, ‘Yes, we did our job’.”