- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Roger Casement and Kerry in 1916

A lack of German support, despite the arms shipment, led Roger Casement to try to warn Volunteer leaders to abandon the Rising, but his message arrived too late, writes Ryle Dwyer

FOLLOWING his retirement from the British consular service, Roger Casement became interested in Irish independence.

He supported the formation of the Irish Volunteers and was one of the principal organisers of the Howth gunrunning to arm the volunteers. It was he who enlisted the services of Erskine Childers to deliver the weapons on his yacht off Howth.

In July 1914, Casement went to the US to organise further assistance, and he was there when the First World War erupted. From as early as September 10, 1914, he wrote to the German Kaiser asking him to segregate Irishmen from among the 35,000 to 40,000 soldiers taken prisoner in Belgium and ensure that “every Irish prisoner was given the option of joining an Irish Brigade similar to that which fought in Fontenoy in 1745 for France against England.” Casement asked the Germans to facilitate the formation of an Irish Brigade made up “of the Irish soldiers and other Irishmen who are at present Prisoners of War in Germany.”

The Germans agreed, but most of the Irish prisoners indignantly resisted effort to get them to turn against the army in which they had been serving. Casement only managed to recruit 56 men from over 2,200 Irish prisoners-of-war.

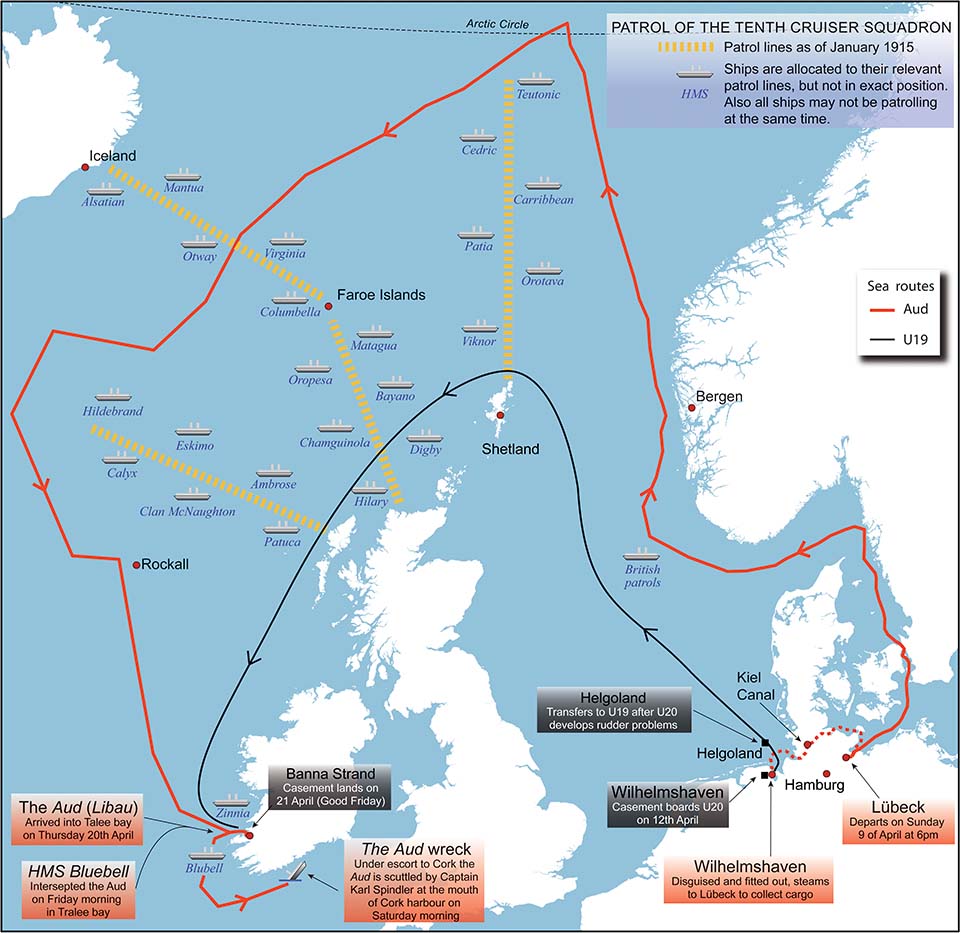

Nevertheless he did persuade the Germans to provide 20,000 rifles and 10 machine guns for the proposed Easter Rebellion. The German navy agreed to ship weapons to Ireland in a dis- guised Norwegian trader, the SS Aud, which left Lübeck on April 9, 1916.

Lieutenant Karl Spindler, captain of the Aud, was under orders to land the weapons at Fenit between Thursday, April 20, and Easter Sunday, April 23.

He was supposed to pick up Casement from a submarine in Tralee Bay and “then to proceed under his instructions.” The Germans wished to send the 56-man Irish Brigade, but Casment would not hear of this. “I shall not have it said that I handed these men over to the hangman,” he insisted.

He had actually become thoroughly disillusioned with the Germans and wished to return to Ireland in an effort to stop the Rising, because the Germans were not providing sufficient help.

If he could not persuade the leaders in Dublin to abandon the idea, however, then he was prepared to support it. When he explained the situation to Robert Monteith, who had been sent out from Ireland through the US to help organise the Brigade, Monteith suggested Casement call off the gun- running. “That can’t be done,” Casement replied.

They were expecting the arms for the rebellion. “If I do anything to stop the ship,” he said, “I shall be- tray them and leave them in the lurch.”

Casement would have preferred to return to Ireland alone, but Monteith insisted on accompanying him, and he persuaded Casement to bring along Daniel Julian Bailey, one of the prisoners-of-war recruited by the Irish Brigade.

He was trained to use the machine guns in the shipment. Casement, Monteith, and Bailey set out for Ireland on April 12, 1916 from Wilhelm- shaven on board the U-20, the submarine that sank the Lusitania off the Cork coast 11 months earlier. The submarine ran into rudder difficulties, and had to put into Hagioland, where Casement and the other two were transferred to U-19.

Two days after U-19 left for Ireland, Berlin received a message from Dublin stipulating that the arms should not be landed at Fenit before the evening of Easter Sunday. The Aud had no radio, so Spindler was not informed he was not expected until the end of the three-day window set for his arrival. He arrived in Tralee Bay on Holy Thursday after- noon, but there was no sign of the U-boat or the agreed signal from the pilot to steer the ship into Fenit pier.

Early the following morning, the U-19 arrived in Tralee Bay, but Weissbach made no effort to locate the Aud, possibly because Casement pressed him to allow him and his two companions to go ashore without delay. The three of them were dis- patched in a small flat-bot- tom boat.

Nearing the shore, the boat capsized in the surf, throwing them into the water. They made it ashore between 3am and 4am. As Casement was suffering from a reoccurrence of malaria, he was in no condition to walk to Tralee, so Monteith and Bailey left him hiding in McKenna’s Fort, overlooking Curraghane, while they went off on foot.

On reaching Tralee, Monteith sought a meeting with the local commandant of the Volunteers, Austin Stack. He told Stack that Casement had returned wishing to “transmit a message to headquarters” to call off the Rising, because the Germans were not providing sufficient help.

“The attempt would be pure madness at the moment,” Casement believed, according to Monteith.

“I could not accept these, as Sir Roger Casement’s views, without having them from his own lips,” Stack explained. He arranged for a car to bring them out to the Banna, but on arrival, they found the area was being search by the Royal Irish Constabulary, and Stack then abandoned the effort to find Casement.

While waiting, Casement failed to keep his head down. He was standing in the fort looking towards the beach around 1.20pm, and did not see RIC Constable Bernard O’Reilly on the road behind him.

The RIC in Ardfert learned a boat was found on the beach early that morning with some weapons nearby, and three strange men were seen coming from the beach. O’Reilly and his Sergeant John Hearn were searching the area around the fort, where the three men had been seen earlier.

O’Reilly spotted Casement standing in the ring fort. “When I first saw him his head and shoulders were appearing over some shrubbery in the fort,” O’Reilly later testified.

Casement gave a false name and said he was the English author of a book on the life of St Brendan. He said he arrived at the fort at 8 o’clock on that morning.

It was a most unconvincing story, and Hearn decided to take him to the RIC station for questioning. Casement was so weak, that they got a young lad, who happened to come along the road in a pony and trap, to take them to Ardfert. On the way they stopped, and a wit- ness identified Casement as one of three men that she saw coming from the beach around 5:15am.

John A Kearney, the head constable in Tralee, recognised Casement and treated him very kindly. He put him into a police recreation room with a fire, in- stead of a cold cell, and sent for a doctor to treat him.

Casement identified himself to the doctor “and expressed the hope that I was in sympathy with the Irish cause,” Dr Mikey Shanahan recalled. “The impression I got was that I should tell the people outside that he was in the barracks and that he had no other purpose in mind only that he might be released which was quite an easy matter at that time.

“The barracks door was wide open and half a dozen men with revolvers could have walked in there and taken Sir Roger away.”

As the doctor was about to leave the building, Kearney showed him a newspaper photograph of a bearded Casement and suggested it looked like the clean-shaven prisoner. “Is not there a remarkable resemblance to the prisoner?” the head constable asked.

“I could see that Kearney knew that the man he had inside was Sir Roger, or was really suspicious that he was Sir Roger, but even so, the prisoner was under no heavy guard,” the doctor noted. Kearney was not looking for information; he was giving Shanahan a subtle warning that the RIC suspected they had Casement, so the Volunteers had better act quickly.

Shanahan informed Stack that Casement could easily be rescued, but Stack pretended not to believe that Casement was the prisoner. This was because he felt unable to attempt a rescue, be- cause Patrick Pearse had ordered during a recent visit that no shot should be fired before the arms were landed at Fenit on Sunday.

When there was no sign of any rescue, Casement asked to speak to a priest. Kearney summoned a priest from the nearby Dominican priory, and allowed him to meet privately with the prisoner. Casement identified himself and asked Fr Francis Ryan to get a message to the Volunteers.

“Tell them I am a prisoner, and that the rebellion will be a dismal hopeless failure, as the help they expect will not arrive.”

Fr Ryan was taken aback. He had no desire to become involved in this kind of politics.

“Do what I ask,” Casement pleaded, “and you will bring God’s blessing on the country and on everyone concerned.”

Next morning Casement, was taken to Dublin on the morning train, in a private carriage in the custody of just one RIC guard. From Dublin, Casement was transferred by boat to Holy- head, and thence to London by train.

On Easter Sunday, he was questioned by Basil Thompson, head of the Criminal Investigative Division at Scot- land Yard, and Admiral William “Blinker” Hall, head of Naval Intelligence.

Casement pleaded to be allowed to appeal to those in Dublin to call off the Rising, but they refused. Hall wished for the Rising to go ahead, so that the London government would then suppress Irish nationalism. “It is better that a cankering sore like this should be cut out,” he insisted.

After agonising about Casement’s request over the weekend, Fr Ryan passed on the message to Stack’s adjutant, Paddy Cahill, on Monday morning. By then, the rebels were already forming in Dublin, and it was much too late to have any impact.

It seemed that anything that could go wrong in Kerry that weekend, had gone wrong.

Map showing the Route of the Aud in 1916