- Home

- Collections

- Atlas Resources for Schools

- Cork Fatality Register

- Mapping the Irish Revolution

- Mapping IRA Companies, July 1921-July 1922

- Mapping the Burning of Cork, 11-12 December 1920

- Martial Law, December 1920

- The IRA at War

- The Railway Workers’ Munitions Strike of 1920

- The Victory of Sinn Féin: The 1920 Local Elections

- The War of Words: Propaganda and Moral Force

- The IRA Offensive against the RIC, 1920

- De Valera’s American Tour, 1919-1920

- The British Reprisal Strategy and its Impact

- Cumann na mBan and the War of Independence

- The War Escalates, November 1920

- The War of Independence in Cork and Kerry

- The Story of 1916

- A 1916 Diary

- January 9-15 1916

- January 10-16, 1916

- January 17-23, 1916

- January 24-30, 1916

- February 1-6 1916

- February 7-14, 1916

- February 15-21, 1916

- February 22-27, 1916

- February 28-March 3, 1916

- March 6-13,1916

- March 14-20, 1916

- March 21-27 1916

- April 3-9, 1916

- April 10-16, 1916

- April 17-21,1916

- May 22-28 1916

- May 29-June 4 1916

- June 12-18 1916

- June 19-25 1916

- June 26-July 2 1916

- July 3-9 1916

- July 11-16 1916

- July 17-22 1916

- July 24-30 1916

- July 31- August 7,1916

- August 7-13 1916

- August 15-21 1916

- August 22-29 1916

- August 29-September 5 1916

- September 5-11, 1916

- September 12-18, 1916

- September 19-25, 1916

- September 26-October 2, 1916

- October 3-9, 1916

- October 10-16, 1916

- October 17-23, 1916

- October 24-31, 1916

- November 1-16, 1916

- November 7-13, 1916

- November 14-20, 1916

- November 21-27-1916

- November 28-December 4, 1916

- December 5-11, 1916

- December 12-19, 1916

- December 19-25, 1916

- December 26-January 3, 1916

- Cork's Historic Newspapers

- Feature Articles

- News and Events

- UCC's Civil War Centenary Programme

- Irish Civil War National Conference 15-18 June 2022

- Irish Civil War Fatalities Project

- Research Findings

- Explore the Fatalities Map

- Civil War Fatalities in Dublin

- Civil War Fatalities in Limerick

- Civil War Fatalities in Kerry

- Civil War Fatalities in Clare

- Civil War Fatalities in Cork

- Civil War Fatalities in the Northern Ireland

- Civil War Fatalities in Sligo

- Civil War Fatalities in Donegal

- Civil War Fatalities in Wexford

- Civil War Fatalities in Mayo

- Civil War Fatalities in Tipperary

- Military Archives National Army Fatalities Roll, 1922 – 1923

- Fatalities Index

- About the Project (home)

- The Irish Revolution (Main site)

Planning to Import Guns in the South West

Fenit Harbour in Kerry was deemed the best place to land guns from the German ships, and it was decided that the rail network would be the best means of distribution of the weapons in the South-west, says Niall Murray

MUCH is often made of the fact that the military strategy for the rising outside Dublin was fairly minimal, but there were long and detailed preparations in the months leading to Easter 1916.

For most who were in- volved, those plans were made with the understanding that they were solely for the importation of guns into the south-west. But many in the highest echelons of the Irish Republican Brother- hood (IRB) knew, or had some notion at least, that something more serious was afoot.

Patrick Pearse visited Cork in August 1915, just a couple of weeks after his now-famous “the fools, the fools, the fools” speech at the graveside of the famous west Cork Fenian Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa in Dublin’s Glasnevin Cemetery. His words having been reproduced in national and local papers in the interim, he was well-feted when attending a feis in North-west Cork three weeks later.

While returning from a feis in Millstreet on Sunday, August 22, the group accompanying him stopped off near the small village of Carriganima.

It is halfway along the 12- mile journey to Macroom, where they planned to take a train back to Cork City. On a hilly piece of ground, Pearse spoke with young local men during the break in the journey.

While ostensibly part of the routine recruiting and awareness-building being undertaken at the time by Pearse as the Irish Volunteers director of organisation, the day’s journey likely served a much more important purpose.

Eight months later, on Easter Sunday, April 23, hundreds of Irish Volunteers assembled in or near Macroom, Carriganima, and Millstreet in what had been intended to be part of the mission to distribute guns supplied through the Germans in support of an IRB-planned Rising. But in August 1915, Patrick Pearse was one of only a handful of men at the very centre of the plot.

It was likely no coincidence, either, that Terence MacSwiney — a full-time paid Irish Volunteers organiser since August 1915 — scouted a route that skirted the Cork-Kerry border in great detail within months of Pearse’s visit.

As second-in-command to Tomás MacCurtain of the Volunteers’ Cork Brigade, a diary he left of his organising work in the autumn and winter of that year shows how much MacSwiney had planned.

Diarmuid Lynch, an IRB Supreme Council member and MacSwiney’s fellow Corkman, was tasked with identifying the location where German guns should land.

It was decided in the weeks after Pearse’s Cork visit that Fenit in Tralee harbour would be the place, and the general consensus among historians is that it was planned to distribute the arms to Volunteers in Cork, Limerick, and as far as Galway.

The idea of holding the line along the Shannon, from Limerick to Athlone probably emerged from earlier plans by the IRB Military Council to bring the guns into the Shannon estuary in Limerick.

Despite the change of landing location, this strategy may have remained in place, requiring the formation of a defensive line from the south-west, near the rugged Cork-Kerry border, up to the midlands.

In order to make the plan viable, the arms sent from the Kaiser’s army in Berlin had to reach Volunteers in Cork, Kerry, Limerick, Clare, and Galway, meaning men needed to stop their distribution being hampered by the arrival of military.

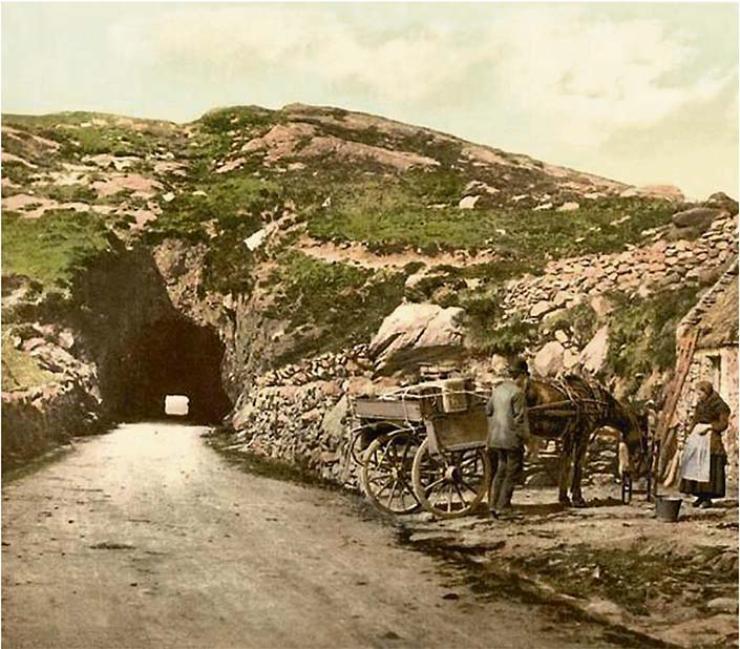

A tunnel on the Glengarriff-Kenmare road which Terence MacSwiney said could be blocked.

MacSwiney’s journal for December 1915 detailed the roads, rail lines, and surrounding landscapes from the river estuary in Ken- mare to Kilgarvan, north through Glenflesk and Barraduff to Rathmore and into north-west Cork to Millstreet and Banteer. He described hedgerow trees on the riverside of the main northern road from Ken- mare to Kilgarvan, and the “very bare and open” country between the road and the mountain to the north. The alternate mountain road running south of the River Roughty is also described.

“Bye-Rds crosses river at Caher and Kilgarvan connecting with main road. River fordable above Sound for either cavalry or infantry,” reads the transcript, held among the copious records from the period collected by Florence O’Donoghue and now held in the National Library of Ireland.

“Road leading up from Castletownbere and Glengarriff to Kenmare. Road from Glengarriff might be blocked at Tunnel,” it continues.

The road surfaces, and mountains and ridges above them (including whether they were bare or rugged), were described as far as Glenflesk and as far as Headford Junction on the way to Rathmore.

“Railway line crosses river just after leaving junction and could be destroyed,” MacSwiney wrote.

For all the secrecty, senior police suspected early in 1916 that just such a plan might be afoot. In a report to senior British administration figures in Dublin Castle seven weeks before the Rising, Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) inspector general Neville Chamber- lain — not to be confused with a future British Prime Minister — outlined his concerns that the Volunteers were being organised with a view to an insurrection.

“...in the event of the enemy being able to effect a landing in Ireland, the Volunteers could no doubt delay the dispatch of troops to the scene by blowing up the railway and bridges provided the organisers were at liberty to plan and direct the operations,” he forewarned.

In fact, once guns had been landed at Fenit, they were to be loaded onto a goods train which the Kerry Volunteers were to arrange from Tralee. Little did the RIC realise when observing noted Dublin trade unionist and councillor William Partridge setting up an ITGWU branch in Fenit in February 1916 that, he had an ulterior motive. He was a right-hand man of Irish Citizen Army leader James Connolly, who had been brought into the secret plan being hatched by the IRB Military Council the previous month.

With the guns aboard the train, some were to be re- moved at Tralee for the Cork and Kerry Volunteers, the rest to continue on the train towards Limerick. From there, they were to be dis- tributed among Volunteers in the West of Ireland.

This plan also depended on being able to cut off out- ward communication from the police and military in Tralee, the main garrison of the Royal Munster Fusiliers. The likely discovery by authorities elsewhere that telegraph or other communications were not working meant Irish Volunteers units were also to be on standby around Kerry — Listowel, Castleisland, and Killarney — to disrupt any forces who might attempt to stop the movement of the arms.

Similarly, the route of possible reinforcements from Cork needed to be blocked. One of the country’s biggest military garrisons was the city’s Victoria Barracks, as was Fermoy. Ballincollig and Ban- don were among the county’s other garrison towns and there were military presences nearer the coast in Kinsale and, in the far south-west, Bere Island.

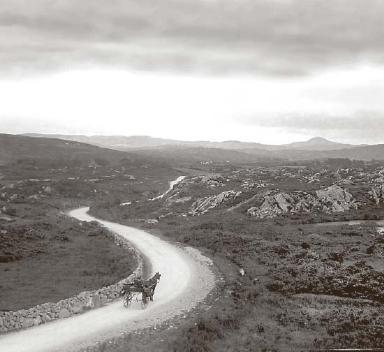

The road between Macroom and Millstreet in 1912. [Photograph, Irish Examiner]

There was clearly, then, a need to cover the possibility of well-armed and highly- trained troops moving in great numbers towards the Kerry border once news of an arms importation and a Rising in Dublin reached their commands.

This appears to explain the detail to which the route was being checked by MacSwiney and others in the final months of 1915, and the importance of the locations to which men were dispatched around Co Cork on Easter Sunday 1916.

Pearse would have shared the gun-running plans by early 1916 with the likes of Kerry’s Irish Volunteers leader Austin Stack and his Tralee Battalion second-in- command Alfred Cotton, whose roles were vital to the intended success of the operation.

Coinciding with regular visits to Dublin for Irish Volunteers executive council meetings, Cork Brigade officers MacCurtain and MacSwiney met occasion- ally with their Kerry counterparts. MacSwiney and Stack may only have realised they were on the same business of organising a Rising when, probably on April 3, they travelled home on the same train as far as Mallow.

Around the same time, Pearse published orders for a national mobilisation exercise on Easter Sunday, April 23, in the armed body’s weekly newspaper, The Irish Volunteer. With large mobilisations of brigades more commonplace in re- cent months, most recently the Volunteers’ prominence in St Patrick’s Day parades up and down the country only a fortnight earlier, it was expected the advertisement of the exercises was expected not to cause any undue alarm to authorities.

Alfred Cotton had planned to place a small force of armed Volunteers at Banna Strand near Fenit, in case anything went wrong during the planned landing of the guns from a German ship. But to avoid giving the plan away because his movements were under constant police watch, IRB Military Council member Seán MacDiarmada told Cotton to comply with an order under Defence of the Realm regulations in early March 1916 that he remain outside Cork and Kerry and live instead in Belfast.

With the minute detail of plans decided over the preceding months, the Cork and Kerry brigades were apparently ready to oversee the landing of German guns. But mishap, confusion, and fate would deal a series of deadly blows to those well- laid plans.