A future of expensive new medicines and tough decisions

When deciding which medicines, treatments, services and programmes to fund, the primary aim should be to reduce uncertainty about expected outcomes according to UCC health economist, Aileen Murphy.

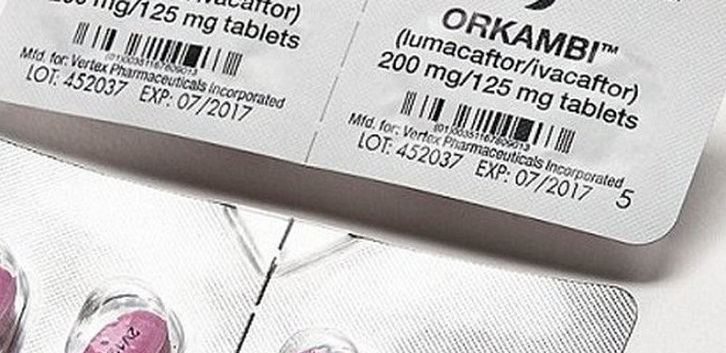

It's a year since cystic fibrosis drug Orkambi was made available in Ireland and so far, the reviews are mixed. While of benefit to some patients (reduced exacerbations, for example) others were unable to tolerate it. Access to Orkambi did not come easily. People took to the streets, talked to Joe and pressure was put on government to fund this "miracle" drug.

"What's the verdict on the cystic fibrosis drug, Orkambi, a year after it has been made available in Ireland," asks UCC health economist @aileenmuphy on @RTEBrainstorm? More: https://t.co/GtZBlvc8Df pic.twitter.com/2ExQePBaDf

— UCC Ireland (@UCC) May 21, 2018

Unsurprisingly, it is now acknowledged that it was not a miracle drug after all, but rather a step towards a miracle. While this is good for cystic fibrosis patients who will need treatment in the future, it is little consolation to those who need treatment now and to those whose access to other healthcare has been delayed owing to the opportunity costs of funding Orkambi.

Rationing in health care is not new. Like in every area, we have greater demands for resources in health than we have resources. Given this scarcity, decisions have to be made on what medicines, treatments, services and programmes to fund and to not fund. With each of these decisions, there is an opportunity cost - if we are using resources to fund one thing, we are foregoing the benefits of using those same resources to fund something else. This phenomenon is neither novel nor temporary: Orkambi doesn’t just represent a "miracle" for cystic fibrosis patients; it symbolises the future of expensive, new medicines and tough decisions.

When making decisions about which medicines, treatments, services and programmes to fund, decision-makers need to rely on what is currently known about it and its comparators. While we have evidence for these medicines from clinical trials, this can be limited and we may have little real-world evidence which would demonstrate how the treatments work outside of ideal trial settings. As a result, we have imperfect information and uncertainty. Consequently, there is a chance that the decision made is the wrong one and the decision may change when further information becomes available, which has significant costs.

A future of expensive new medicines & tough decisions: @aileenmurphy_ @CUBSucc @UCC on the decision process around new medicines, treatments, services & programmes https://t.co/ftpytU4dvc pic.twitter.com/sU1Sjz9hdz

— RTÉ Brainstorm (@RTEBrainstorm) May 21, 2018

If a medicine or treatment is falsely rejected, patients are denied access to life saving/altering treatments. Alternatively, if a medicine or treatment is falsely accepted, patients are exposed to treatments that may not be effective. Therefore, it is important that funding decisions are neither rushed nor delayed. Achieving this balance is challenging and will become more demanding as new medicines and treatments become available that are for smaller populations or rare diseases and also with the advent of personalised medicine.

Nevertheless, there are potential solutions available to balance the tensions between granting appropriate access and generating additional information. Reimbursement schemes that go beyond traditional "yes or no" dichotomous coverage decisions and co-ordinate structured data collection are one solution. These are known as "Performance-Based Risk Sharing Agreements" and have been employed elsewhere in various forms, for example in the UK ("Only in Research") and Canada ("Coverage with Evidence Development").

Their primary aim is to reduce uncertainty about expected health outcomes. This may involve collecting data on how the treatment performs in populations different to those considered in the trials. Such schemes or programmes are initiated following regulatory approval, but prior to full diffusion of the medicine/treatment and involve data collection as agreed upon between the manufacturer and the payer. The price and reimbursement of the technology are linked to the programme outcomes, either explicitly or implicitly, and redistribute risk between the payer and manufacturer.

Traditionally, evidence was generated by the manufacturer with the payer funding or not funding the medicine/treatment based on that evidence. However, the landscape of medicines is changing, with more new and orphan drugs, for smaller populations. Patients and their clinicians want faster access to life saving and improving treatments. Manufacturers want to improve return on research and development and incentives for future innovations. And payers want to balance access and affordability.

As a result, how we generate evidence and make decisions needs to change. We need to acknowledge that evidence can and will evolve. Furthermore, this needs to be incorporated into decision making processes so systematic, evidence-based decisions can be made. We need to examine Performance Based Risk Sharing Agreements or similar, encourage the collection of additional information to reduce uncertainties and provide the opportunity to re-examine decisions.

Implementing such schemes are arduous and require careful planning. Nevertheless, change is needed; the current "call Joe" or "shout the loudest" system for every "miracle drug" is not sustainable given the surge of expensive novel drugs coming our way.

Dr Aileen Murphy is a lecturer in health economics at Cork University Business School at UCC

Follow @aileenmurphy_

This article first appeared on RTÉ Brainstorm. Visit here

For more about business education and research at UCC visit here

Media: For further information contact Ruth Mc Donnell, Head of Media and Communications, Office of Marketing and Communications, UCC Mob: 086-0468950