In This Section

“Let No Irishman Throw a Stone at the Foreigner”: Remembering and Forgetting Solidarity in Contemporary Ireland

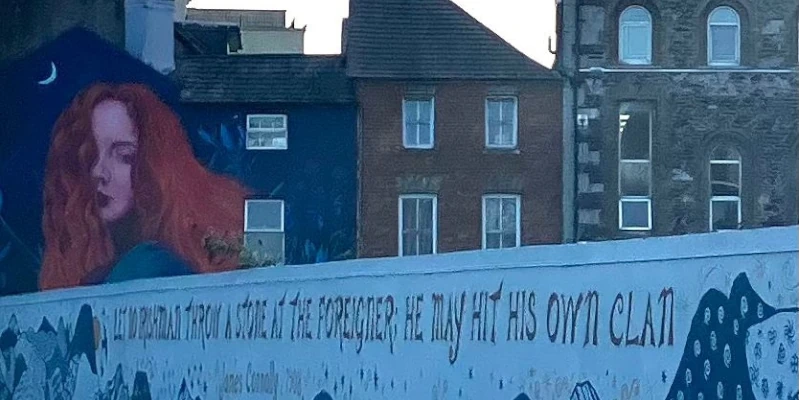

Walking through the streets of Cork, a recent mural by the artist Claire Coughlan reads:

“Let no Irishman throw a stone at the foreigner; he may hit his own clansman’’— James Connolly

It is a striking reminder of Connolly’s vision of solidarity – one that rejects the politics of exclusion and recognises the shared histories of displacement and oppression. Yet, beneath this powerful appeal lies a deeper tension: what does it mean for a postcolonial, now increasingly diverse Ireland, to memorialise Connolly’s words at a time when the anti-immigration far-right movement is fuelling hostility and discrimination against migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in Ireland?

Connolly’s warning “he may hit his own clansman” evokes an ethical stance and a historical truth. For centuries, Irish people were the “foreigners” elsewhere – in Britain, in America, and in other colonies. The irony of contemporary Ireland’s anti-immigrant rhetoric is that it forgets how recently Irishness itself was stigmatised, racialised, and violently othered. This forgetting becomes clearer when we revisit the history told in John Archer Jackson’s The Irish in Britain. Tracing Irish migration from the sixteenth century to the modern period, Jackson’s work exposes how the Irish were once among the most despised minorities in British society. In the 19th century, Irish labour was indispensable to Britain’s industrial expansion. They dug canals, built railways, and served in the army, yet, Irish people were systematically dehumanised.

Anti-Irish racism was common in media and everyday life, reproducing long-standing stereotypes of the “dirty”, “drunken”, or “violent” Irishman. In addition, landlords and employers often blacklisted Irish names echoing older “No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish” signs exposing how Irishness functioned as a conditional form of whiteness in Britain. This racialisation of the Irish shows that whiteness itself is hierarchical and historically contingent. The Irish were thus racialised within Europe — seen as white yet inferior, European yet uncivilised.

This history complicates any straightforward narrative of Irish whiteness or integration. The Irish experience in Britain reminds us that “race” is not fixed but contingent, that belonging and exclusion are produced through shifting hierarchies of value, labour, and respectability. Jackson’s analysis helps us see Connolly’s appeal to solidarity in a new light. When he warned Irish workers not to “throw stones at the foreigner,” Connolly was articulating a politics grounded in shared dispossession. The Irish working class, exploited in Britain and at home, had more in common with colonised people and migrant labourers than with their own elites. His socialism was, in this sense, internationalist, a recognition that the oppression of one group is bound up with that of another.

The Stone and the Border: Connolly’s Ireland and the New Others

The resonance between Jackson’s portrayal of the Irish in Britain and the experiences of migrants in Ireland today is striking. Then, as now, the same discourses persist in portraying migrants as welfare-dependent, scapegoats for the housing crisis, culturally incompatible, or threatening to the social order, when the reality is far from that. Ireland’s transformation from a nation of emigrants to one of immigrants has not erased the logic of othering; it has merely redirected it. The prejudice that once targeted the Irish is now, at times, reproduced by them. The mural’s call to solidarity, then, demands not nostalgia but self-reflection: how does a society built on memories of exile respond to the arrival of new exiles at its shores?

This question felt uncomfortably alive on the 7th of June in Cork. As I made my way through the city, thousands gathered for two opposing protests: a pro-Palestine rally and, nearby, an anti-immigration demonstration. Both carried flags, chants, and conviction. Walking toward the pro-Palestine protest, I found myself wondering who was going where and who, among us, was being marked as belonging or not. It was a surreal experience: to walk as a migrant between two expressions of collective identity, one calling for justice and liberation, the other invoking nationalism and exclusion.

For a moment, the city seemed divided between two moral geographies: one global and solidaristic, the other inward-looking and defensive. People holding the tricolour that was once a symbol of anti-colonial resistance and unity fluttered above both crowds, though it holds different meaning for each of them. For some, it was a banner of empathy with the oppressed; for others, a boundary marker of who counts as “Irish.” That day, walking through the rain, I felt what it means to be “the other” again.

This moment in Cork was not isolated. It exposes the contradictions of contemporary Irish nationalism, it struggles between the memory of suffering and the politics of exclusion, between the promise of solidarity and the fear of difference. It is precisely here that Connolly’s mural speaks again. In today’s Ireland, where anti-immigrant rhetoric is amplified online and the tricolour is increasingly brandished as a flag of hate, Connolly’s words feel like an urgent reminder. His statement challenges the very politics of bordering and ordering, calling for interconnection over separation, reminding us that our fates are linked; for solidarity over hierarchy, insisting that the struggle for dignity is one; and for historical consciousness over amnesia, warning that to forget our past is to weaponise it against others.

Ultimately, the mural is not an answer but a provocation. To honour Connolly’s legacy is not merely to repeat his words, but to complete his thought and work on building solidarity that dismantles the racial and bureaucratic walls he could not have fully anticipated. The stone must not simply be dropped; it must be thrown through the windows of exclusionary politics itself, demanding a nation that sees the “foreigner” not as a threat, but as a future clansman.

Yet this vision has its limits. Connolly’s idea of “clansmanship” appealed to a shared human stock, but it did not and perhaps could not, in his time confront the global colour line or the racial logics underpinning colonialism. His anti-imperialism was radical but not yet decolonial. He could not have foreseen an independent Ireland participating in the EU’s violent bordering regimes, which marks a direct contradiction of his “solidarity beyond borders.”

This is the critical gap. Connolly saw the Irish struggle as part of a global fight against exploitation, yet the Irish state now operates within systems that reproduce it. His call for solidarity between Irish workers and migrants remains urgent, but it is undermined by a state apparatus that benefits from the precarity and exclusion of those very migrants.

And yet Connolly was also a nationalist. His dream of an independent socialist Ireland was inseparable from his commitment to national liberation. This dual commitment forms both the beauty and the limit of his vision. The mural’s revival of his words in contemporary Cork captures the inclusive sentiment but strips away its radical context. Today, I wonder if the quote circulates as a moral slogan rather than a structural critique of capitalism, imperialism, nationalism, and the borders they produce.

Here lies the critical silence. Nationalism, even a liberatory one, can be blind to its own exclusions. The independent Ireland that Connolly helped imagine was never designed for a multicultural or post-migrant reality. The “foreigner” in today’s Ireland — the asylum seeker in Direct Provision, the care worker from the Philippines, the African taxi driver — encounters a society that remembers its own exile yet often reproduces the same hierarchies of belonging and violent forms of exclusion once used against its people.

For more on this story contact:

Dr Kheira Arrouche is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow on the MIGMOBS project at University College Cork, where she leads a study on African migration and mobility in Ireland.

MIGMOBS ERC AdG Project

Contact us

Radical Humanities Laboratory, Wandesford Quay Research Facility, University College Cork, Republic of Ireland

- migmobs@ucc.ie

- Professor Adrian Favell, Project PI